|

Honestly, the word “core” has become so hackneyed that it makes me kind of ashamed that our profession. I mean, let’s face it: “Core” can essentially be translated as “The rectus abdominus, lumbar erectors, obliques, and all those other muscles between the knees and shoulders that I’m either too lazy or misinformed to list.”

Everything is related; our bodies are great at compensating. As such, it’s imperative that the approach one takes to “core” training be based on addressing where the problems exist. The most common lower back problems we see are related to extension-rotation syndrome. We most often get hyperextension at the lumbar spine because our gluteus maximus doesn’t fire to complete hip extension and posteriorly tilt the pelvis; we have to find range of motion wherever we can get it. Having tight hip flexors and lumbar erectors exaggerates anterior pelvic tilt, so this hyperextension is maintained throughout the day to keep the body upright in spite of the faulty pelvic alignment.

The rotation component simply comes along when you throw unilateral dominance into the equation. It might be a baseball pitcher always throwing in one direction, or an office worker always turning to answer the phone on one side. Lumbar rotation is not a movement for which you want any extra range of motion, and the related hip hiking isn’t much fun to deal with, either.

The solution is to get the glutes firing and learn to stabilize the lumbar spine while enhancing mobility at the hips, thoracic spine, and scapulae. You just have to get the range of motion at the right places.

Unfortunately, thinking this stuff out isn’t high on some people’s priority list. It’s “sexier” to tell a client to do some weighted sit-ups, Russian twists, and enough yoga to make the hip flexors want to explode. I’m not going to recommend sit-ups to anyone, and if an athlete is going to do something advanced, he’s going to have shown me that he’s prepared for it by successfully completing a progression to that point. You can get away with faulty movement patterns in the real world, but when you put a faulty movement pattern under load in a resistance training context, everything is magnified.

Eric Cressey

Start with the right plan. |

| Read more |

|

This is the foundation for everything. I’d like to be able to give you a quick-fix answer, but the truth is that nothing will ever go as far as elbow grease and perseverance. It sucks, but work long hours - longer than you could even imagine. I have regularly worked 80+ hour weeks for as long as I can remember; at times, it has been 40 of athletes/clients (some for free) and 40 of writing/online consulting/forum responses. I did it in the past so that I could get to where I am now, and I do it now to capitalize on the foundation I put down in the past and so that I can spend time with my family when that day comes.

I had a conversation with Mike Boyle on this back in December, and asked him flat-out where I should draw the line on work and play. His response: "At your age, you don't. Sleep in the office if you have to. It'll all pay off." You won't find someone who works harder than I do, and when one of the most sought-out performance enhancement coaches in the history of sports gives an overachiever like me that kind of encouragement, you not only pay attention; you go from really productive to crazy productive.

So, in short, the truth is that I have busted my butt from day one and wouldn’t be here if I hadn’t done so. I didn’t spend a penny on alcohol in my college career; it was better spent on resources such as books, DVDs, seminars, and quality food and supplements to make me the lifter and coach that I am today. I never went on Spring Break; I worked in gyms and with athletes at universities for every single one of them through my six years of college education (undergraduate and graduate).

I didn’t abuse my body with excessive late nights – or any alcohol or drugs – because I knew how such behavior would affect my training, coaching, and writing. I haven't even watched an episode of Survivor, 24, American Idol, Lost, Alias, Will and Grace, The Apprentice, or any of a number of other popular shows I'm forgetting to mention; I'd just rather be doing other things. Don't get me wrong; I've still had fun along the way, but I've gotten better about finding a balance. Life is all about choices, and I chose to be where I am today.

Eric Cressey

Have you ever wondered what separates the average trainers from the best of the best? |

| Read more |

|

Eric Cressey

In addition to learning outside the gym, right off the top of your head, what are five things that our readers can do right now to become a better lifters, athletes, coaches, and/or trainers.

Bob Youngs

1) A good program must include: movement prep, flexibility work, injury prevention work, core work, cardio work, strength training, and recovery/regeneration work. Does that sound familiar? In other words, construct programs that incorporate all aspects.

2) Read one book per week. If you ever come over to my house you will see hundreds of books. I shoot for one new book per week.

3) Network within your given sport or profession. If you are a powerlifter, seek out lifters stronger than you and learn from them. If you are a strength coach, seek out another coach you think has something to offer that you don’t have. You get the idea. Most people are willing to share information if you ask them; this is usually the way you will learn the most.

4) Work smarter. Many people work hard; what makes a person the best at any given task is usually working smarter.

5) Have properly defined and realistic goals, and write them down. I am shocked by the amount of athletes and coaches who have one broad goal and no steps to get there. Set a big goal and then break it down into smaller goals. I will use a powerlifter as an example. I hear all the time, “I want to squat 800 pounds.” That’s great, but how do you get there? If you have a current max of 500, your next small goal might be to squat 550. Then, you break that down further to knowing you need to hit X on a given max effort exercise. Now, you have a goal every time you go into the gym. |

| Read more |

|

| Q: I have an imbalance - one leg vs. the other. Do you suggest doing 100% unilateral leg-work for a while to cure the imbalance?

A: This is a tough one to answer; it's never as simple as "right and left." Generally, you'll see muscles on each side that are a bit stronger or weaker. For example, in right-handed individuals, they'll typically be stronger on lunging movements with the left leg forward. The left ITB/TFL, right quadratus lumborum, and right adductors will be tight, while the right hip abductors, left adductors, and left quadratus lumborum will be weak.* There are more complex ramifications at the ankle and foot, too. Often, the best way to address the unilateral imbalance in a broad sense is to figure out where people are tight/weak and address those issues. I've seen lunging imbalances corrected pretty easily with some extra QL work or pure stabilization work at the lumbar spine. The tricky thing about just doing extra sets on one side is that your body will often try to compensate for the imbalances. You might get the reps in, but are you really doing anything to even yourself out if you're just working around the dysfunction?

This is just some stuff to consider. I don't think doing more on that side will hurt, but it won't always get you closer to where to want to be.

Eric Cressey |

| Read more |

|

| Here it is, the grand finale.

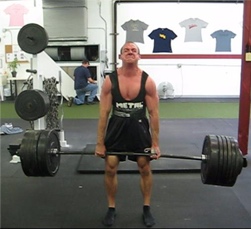

In Part I of this series, I introduced you to a collection of deadlifting prerequisites needed to qualify my recommendations to you — and enable you to determine if deadlifting is right for you in the first place.

In Part II, I covered the good, the bad, and the ugly of the conventional deadlift, the cornerstone of the deadlifting world.

With the prerequisites and the general technique issues resolved, it's time to diversify and look at several deadlifting variations you can use to give your training plenty of variety without losing out on the tremendous benefits of heavy pullin'!

Continue Reading... |

| Read more |

|

Q: I am a strongman competitor and am thinking about incorporating squat briefs into my training. I talked to a powerlifter buddy of mine and he said he would recommend briefs for max effort squats and deadlifts to keep the hips healthy. What do you think about this?

A: Well, my first observation is that you’re not going to be using the briefs in competition, are you? Specificity is more important than people think; what’s specific for a powerlifter won’t necessarily be specific for a strongman.

However, given the nature of the training you’ll be doing (powerlifting-influenced), I wouldn’t rule the briefs out right away. It depends on whether you're regularly box squatting and/or squatting with a wide stance. If you are, I'd say that they're a good investment, and you could use them 1-2 weeks out of the month.

I would, however, caution against using them as a crutch against poor lifting technique. There are a lot of guys who just throw on briefs because their hips hurt, not realizing that it isn't the specific exercise that is the problem; it's the performance of that exercise that gives them trouble. For example, hamstrings dominant hip extension/posterior pelvic tilt allows the femoral head to track too far anteriorly and can cause anterior hip pain. If the glutes are activated appropriately, they reposition the head of the femur so that this isn't a problem. Unfortunately, a good 80% of the population doesn't have any idea how to use their glutes for anything except a seat cushion.

Eric Cressey

Efficient Athletes will always be Better Athletes |

| Read more |

|

Q: I figure you would be a good person to ask about a question I have; it deals with excessive dorsiflexion and athletes. Kelly Baggett was explaining how people with excessive dorsiflexion rarely are good athletes. He said it is related to hip position. Could you elaborate on the subject?

A: As usual, Kelly is right on the money! I honestly wonder if the two of us are on some sort of wavelength with one another, as I think you could use our thoughts interchangeably in most cases!

To answer your question, if there is too much dorsiflexion at the ankles, it is generally a sign that you're not decelerating properly at the knees and hips, so the ankles are taking on an extra percentage of the load. I would suspect weakness of the knee and/or hip extensors.

To be honest, though, not many people are really capable of excessive dorsiflexion, as their calves are so tight. I suspect he's referring more to the fact that the heel is further off the ground and the knee is tracking forward too much as compensation (related to the quads being overactive, too). If you look at the research on jump landings in female athletes, you’ll find that they land with considerably more knee flexion than their male counterparts. We know that weak hamstrings are very common in females, and that this is one reason for their increased risk of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. The hamstrings are hip extensors, meaning that they also decelerate hip flexion. If they don’t have enough explosive and limit strength to control the drop of the hips upon landing, there’s no other option but to flex the knees extra to cushion the drop. It’s an unfortunate trend that just plays back into the quad-dominance (deceleration of knee flexion).

Obviously, dynamic flexibility plays into this tremendously, too. If you can't get ROM in one place, your body will seek it out elsewhere.

Eric Cressey

Step-By-Step what it Takes to Become a Superior Athlete |

| Read more |

|

In December of 2001, I was rear-ended going about 30mph; five cars were involved, and I was the first car hit from behind. My knee hit the dashboard when I was hit from behind and my head was jerked backwards when I hit the car in front of me.

My knee started hurting soon after, although I never got it checked out. It’s now become a sharp pain and a constant, dull ache as well with weakness on stairs and squatting-type positions especially. In addition, there are tender areas, on the outside and top of the knee, that cause extreme pain when I am bending, squatting, lying down, or sitting down for too long. My hip has also been affected, also aching constantly. My right leg and knee also hurt and knot up easily. The surrounding muscles are very weak with several knots in them, and I also have a very tight iliotibial band. Any ideas what might be going on?

I thought "PCL" (posterior cruciate ligament) the second I saw the word "dashboard;" it's the most common injury mechanism with this injury. I’m really surprised that they didn’t check you out for this right after the accident; you might actually be a candidate for a surgery to clean things up. Things to consider:

1. They aren't as good at PCL surgeries as they are with ACL surgeries, as they're only 1/10 as common. As such, they screw up a good 30%, as I recall – so make sure you find a good doctor who is experienced with this injury to assess you and, if necessary, do the procedure.

2. It's believed that isolated PCL injuries never occur; they always take the LCL and a large "chunk" of the posterolateral complex along for the ride. That would explain some of the lateral pain.

3. The PCL works synergistically with the quads to prevent posterior tibial translation. As such, quad strengthening is always a crucial part of PCL rehab (or in instances when they opt to not do surgery). A good buddy of mine was a great hockey player back in the day, but he has no PCL in his right knee; he has to make up for it now with really strong quads.

4. Chances are that a lot of the pain you’re experiencing now is related more to the compensation patterns you’ve developed over the years than it is to the actual knee injury. For instance, the tightness in your IT band could be related to you doing more work at the hip to avoid loading that knee too much. Pain in the front of the knee would be more indicative of a patellar tendonosis condition (“Jumper’s Knee”), which would result from over-reliance on your quads because of the lack of the PCL (something has to work overtime to prevent the portion of posterior tibial translation that the PCL normally resisted).

5. From an acute rehabilitation standpoint, I think you’d need to address both soft tissue length (with stretching and mobility work) and quality (with foam rolling). These interventions would mostly treat the symptoms, so meanwhile, you’re going to need to look at the deficient muscles that aren't doing their job (i.e. the real reasons that ITB/TFL complex is so overactive). I'll wager my car, entire 2006 salary, and first-born child that it’s one or more of the following:

a) your glute medius and maximus are weak

b) your adductor magnus is overactive

c) your ITB/TFL is overactive (we already know this one)

d) your biceps femoris (lateral hamstring) is overactive

e) your rectus femoris is tighter than a camel's butt in a sandstorm

f) you might have issues with weakness of the posterior fibers of the external oblique, but not the rectus abdominus (most exercisers I know do too many crunches anyway!)

Again, your best bet is to get that PCL checked out and go from there. If you’ve made it from December 2001 until now without being incapacitated, chances are that you’ll have a lot of wiggle room with testing that knee out so that you can go into the surgery (if there is one) strong.

Eric Cressey |

| Read more |

|

Eric Cressey

They say that experience is the only thing that can truly yield perspective; I’d say that you’re a perfect example of that. Speaking of experience, what were some of the mistakes you’ve made along the way, and what would you do differently?

Bob Young

I’m not even sure where to start on this one. The easiest way to explain this would be to quote Alwyn Cosgrove, “A complete training program has to include movement preparation, flexibility work, injury prevention work, core work, cardiovascular work, strength training, and recovery/regeneration. Most programs cover, at best, two of those.”

My program only included strength training and some core work for the longest time, and I am now paying for that with chronic injuries. Now, I have had to learn about the other parts that I was missing; the more I incorporate this stuff, the better I feel. However, 15 years of not doing what I should have been doing has really cost me. I have torn my pec major, triceps tendon, intercostal, and biceps tendon. I also currently have a bulging disk in my lower back.

Could all these have been avoided? Probably not all of them, but I think some of them could have. If I had to name the biggest mistakes, it would be not using a foam roller and not doing any mobility work. In the two months I have been using the foam roller my tissue quality has improved dramatically. I have been doing mobility work, under your guidance, for about a month and I have seen some incredible improvements.

Eric Cressey

Correct your Training and Improve your Performance. |

| Read more |

|

From reading your stuff and that of John Berardi, I’ve really begun to reconsider the traditional bodybuilding-influenced “bulk-cut” approach to improving body composition. With respect to getting people to below 10% body fat, Dr. Berardi wrote that “people usually OVERESTIMATE the difficulty and UNDERESTIMATE the duration,” and that it is possible as long as:

1) They're willing to work out in excess of 5hrs per week (sometimes up to 8 hours/week).

2) They're willing to commit to eating better with each meal. Not follow a fat loss or bulking diet. Simply, every time they sit down to eat, they do better.

3) They're willing to learn a new normal. We all have habits that are ‘normal’ and if you're 15, 20, 30% fat, your ‘normal’ = good for fat gain. A diet is abnormal. You'll always get back to 15%, 20%, 30% if you're always doing something abnormal. However if you re-learn a new normal, you can have a new body.

Judging from your writings, you seem to favor a similar approach. I was just wondering if you would care to elaborate on any of these things. I’ve really been thinking about how traditional bulking and cutting might very well be outdated, and would appreciate your thoughts.

Those are definitely some statements with which I agree wholeheartedly, and I think that the more people that check out JB’s Precision Nutrition products, the less often I’ll have to encounter questions like this! Once people start to adopt these ideals, I really think that we’ll see a paradigm shift in the world of training-nutrition interaction for body composition improvement.

I, too, get really sick and tired of the “bulk and cut” mentality to which so many people adhere. And, as a competitive athlete myself who has to maintain reasonably strict control over my body weight – yet has still seen consistent improvements in body composition over time – I feel that I have a solid frame of reference from which to speak. In fact, as I look to drop a few pounds prior to APF Senior Nationals (June 2), my overall training and nutrition strategies aren’t changing much at all.

With that said, I've got several problems with what has seemingly become the “traditionalist” approach:

1. People adopt programs, but never habits. Consistency is more important than you can possibly imagine, but when you're constantly shuffling back and forth between programs, you're never really "getting it." If you had the good habits in the first place, chances are that you wouldn’t have ever had to come to consider the extreme cutting or bulking, right?

2. Progress can be very tough to monitor in experienced individuals. Experienced natural lifters might be lucky to add five pounds of lean body mass a year. How realistic is it to really micromanage such subtle changes over a three-month period (assuming two bulks and two cuts per year)? Spread five new pounds out over an entire body and you'll see that it isn't readily apparent. Work with some guys who are 7-feet tall like I have and you’ll see that it’s even more hard to notice – especially when you see them on a daily basis.

3. Bulk/Cut is no way to live. Let's assume that a year consists of two bulks and two cuts. So, basically, you're spending one half of the year gorging yourself until you become a fat-ass, and the other half in misery until you get lean enough to feel crappier and look better. Toss in a few root canals, a colonoscopy, and a few Ben Affleck movies*, and you’ve got yourself a year to be forgotten. Yeehaw.

4. Think of the long-term consequences of the bulk/cut scheme. If you read the research on weight regain and body fat distributions in recovered anorexics, you’ll see that central adiposity is extremely common. Are severe cutting diets really that much different than clinical cases of anorexia? Taking someone’s thyroid out and stomping on it would actually be a quicker means to the same end.

5. Do we really want to adhere to guidelines that are predominantly geared toward professional bodybuilders who are so juiced to the gills that you can smell GH on their breath? They’ve got extensive anabolic arsenals in place to maintain muscles mass and optimize nutrient partitioning as they diet down, and thyroid medications to keep their metabolic rates up in spite of the reductions in calories. Indirectly, all these substances improve strength and stave off lethargy, making training sessions more productive in spite of caloric reductions. In the bulking scenarios, the nutrient partitioning effects are still in place, as these individuals are less likely to add body fat when eating a caloric surplus.

Now, put a natural lifter in the same scenario, and you’ll see right away that he’s immediately at a disadvantage. Drop calories too fast, and your endogenous testosterone and thyroid levels fall. You get tired and weak, and your body has to find energy wherever it can – even if it means breaking down muscle tissue.

I’m not trying to get on a soapbox here; I’m just trying to make people realize that they’re comparing apples and oranges. You need to do what’s right for you.

And what does that entail? Adopt admirable dietary, training, and lifestyle habits, and you’ll build a strong body that moves efficiently and just so happens to look good. Leave the quick-fix approaches for those with “assistance” and anyone silly enough to watch a fitness infomercial from beginning to end.

Eric Cressey |

| Read more |

|

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|