|

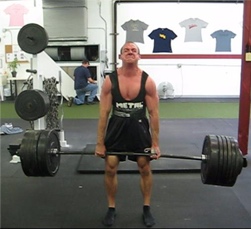

Yesterday, I deadlifted 600 for three reps for the first time. This is a number I've been after for quite some time.

After the lift, I got to thinking about some good lessons I could "teach" in light of this milestone for me. Here are five quick Saturday morning thoughts:

1. Personal records sometimes happen when you don't expect them.

I honestly didn't feel particularly great when I started the training session yesterday. In fact, if you'd asked me prior to the lift if I was going to be setting a PR in the gym that day, I would have said, "Absolutely not." However, a thorough warm-up and a few extra sets of speed deadlifts on the "work-up" did the trick. Make sure to never truly evaluate where you stand until you've actually done your warm-up.

2. It's really important to take the slack out of the bar.

If you watch the video above, you'll notice that I pull the bar "taut" before I ever really start the actual lift. Every bar has a bit of slack in it, and you want to get rid of it early on. Check out this video on the subject:

You can actually get a feel for just how much slack there is in the bar if you observe how much it bends at the top under heavy weights. This doesn't happen to the same degree with "regular" barbells.

3. Don't expect to accomplish a whole lot in the training session after a lifetime PR on a deadlift.

Not surprisingly, heavy deadlifting wipes me out. Interestingly, though, it wipes me out a lot more than heavy squatting. From a programming standpoint, I can squat as heavy as I want - and then get quality work in over the course of the session after that initial lift. When the "A1" is a deadlift, though, it's usually some lighter, high-rep assistance work - because I mostly just want to go home and take a nap after pulling any appreciable amount of weight!

4. Percentage-based training really does have its place.

For a long time, I never really did a lot of percentage-based training for my heavier work. On my heavy days, it was always work up, see how I felt, and then make sure to get some quality work in over 90% of my 1RM. As long as I was straining, I was happy. Then, I got older and life got busier - which meant I stopped bouncing back from these sessions as easily. Percentage-based training suddenly seemed a lot more appealing.

I credit Greg Robins, my co-author on The Specialization Success Guide, with getting me on board the percentage-based training bandwagon. He was smarter than me, and didn't wait to get old to start applying this approach when appropriate.

5. You've got to put force in the ground.

This is a cue I've discussed at length in the past, but the truth is that I accidentally got away from it for a while myself. Rather than thinking about driving my heels through the floor to get good leg drive, it was almost as if I was trying to "just lift the bar." It left me up on my toes more than I wanted, and my hamstrings got really cranky.

I took a month to back down on the weights and hammer home the heels through the floor cue with speed work in the 50-80% range, and it made a big difference. I've got almost 15 years of heavy deadlifting under my belt, and even I get away from the technique that I know has gotten me to where I am. Technical improvement is always an ongoing process.

Looking for even more coaching cues for your deadlift technique? Definitely check out The Specialization Success Guide. In addition to including comprehensive programs for the squat, bench press, and deadlift, it also comes with detailed video tutorials on all three of these "Big 3" lifts. And, it's on sale at the introductory $30 off price until tonight at midnight. Check it out HERE.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

With the release of The Specialization Success Guide, I got to thinking about some of my biggest mistakes with respect to developing the Big 3 (squat, bench press, and deadlift). Here are the top five mistakes I made in my powerlifting career:

1. Going to powerlifting equipment too soon (or at all).

Let me preface this point by saying that I have a tremendous amount of respect for all powerlifters, including those who lift in powerlifting equipment like bench shirts and squat/deadlift suits. Honestly, they just weren't for me.

I first got into a bench shirt when I was 160 pounds, and my best raw bench press was about 240-250 pounds. I was deadlifting in the high 400s, and squatting in the mid 300s. In hindsight, it was much too soon; I simply needed to develop more raw strength. My squat and bench press went up thanks to the suit and shirt, respectively, but just about everything I unracked felt insanely heavy. I just don't think I had enough training experience under my belt without any supportive equipment to feel truly stable under big weights. It's funny, though; my heaviest deadlifts never felt like this, as it was the "rawest" of any of the big 3 lifts for me.

There's more, though. Suits and shirts were just an annoying distraction for me. I absolutely hated the time and nuisance of having to put them on in the middle of a lift; training sessions easily dragged on to be three hours, when efficiency was something I'd always loved about my training. Perhaps more significantly, getting proficient with equipment took a lot of time and practice, and the more I was in it, the less athletic I felt. I spent too much time box squatting and not enough free squatting, and felt like I never developed good bottom-end bench press strength because the shirt did so much of the work for me.

At the end of my equipped powerlifting career, I had squatted 540, bench pressed 402, deadlifted 650, and totaled 1532 in the 165-pound weight class. Good numbers - enough to put me in the Powerlifting USA Top 100 for a few years in a row - but not quite "Elite." I tentatively "retired" from competitive powerlifting in December of 2007 when Cressey Sports Performance grew rapidly, but kept training - this time to be athletic and have fun.

For the heck of it, in the fall of 2012, I decided to stage a "raw" mock meet one morning at the facility. At a body weight of 180, I squatted 455, bench pressed 350, and deadlifted 630 for a 1435 total. In other words, I totaled "Elite" by 39 pounds...and did the entire thing in 90 minutes.

Looking back, I think I could have been a much more accomplished competitive lifter - and saved money and enjoyed the process a lot more along the way - if I'd just stuck with raw lifting. Again, I don't fault others for using bench shirts and squat/deadlift suits, but they just weren't for me. I would just say that if you do decide to go the equipped route, you should be prepared to spend a lot more time in your equipment than I did, as my dislike of it (and lack of time spent in it) was the reason that I never really got proficient enough to thrive with it in meets.

2. Not understanding that fatigue masks fitness.

Kelly Baggett was the first person I saw post the quote, "Fatigue masks fitness." I thought I understand what it meant, but it wasn't until my first powerlifting meet that I experienced what it meant.

Thanks to a powerlifting buddy's urging, I went out of my way to take the biggest deload in my training career prior to my first meet. The end result? I pulled 510 on my last deadlift attempt - after never having pulled more than 480 in the gym.

You're probably stronger than you realize you are. You've just never given your body enough of a rest to actually demonstrate that strength.

3. Not getting around strong people sooner.

I've been fortunate to lift as part of some great training crews, from the varsity weight room at UCONN during my grad degree, to Southside Gym in Connecticut for a year, to Cressey Sports Performance for the past seven years.

When I compare these training environments to the ones I had in my early days - or even what I experience when I have to get a lift in on the road at a commercial gym - I can't help but laugh. Training around the right people in the right atmosphere makes a huge difference.

To that end, beyond just finding the right program, I always encourage up-and-coming lifters to seek out strong people for training partners, even if it means traveling a bit further to a different gym. Success happens at the edge of your comfort zone, and sometimes that means a longer commute and being the weakest guy in a room.

4. Spending too much time in the "middle zone" of cardio.

A lot of powerlifters will tell you that "cardio sucks." I happen to think it's a bit more complex than that.

Doing some quality work at a very low intensity (for me, this is below 70% of max heart rate) a few times a week can offer some very favorable aerobic adaptations that optimize recovery. Sorry, but it's not going to interfere with your gains if you walk on the treadmill a few times a week.

Additionally, I think working in some sprint work with near-full recovery can be really advantageous for folks who are trying to get stronger, as it trains the absolute speed end of the continuum.

As I look back on the periods in my training career when I've made the best progress, they've always included regular low-intensity aerobic work - as well as the occasion (1x/week) sprint session. When did cardio do absolutely nothing except set me back? When I spent a lot of time in the middle zone of 70-90% of max heart rate; it's no man's land! The take-home lesson is that if you want to be strong and powerful, make your low-intensity work "lower" and your high-intensity work "higher."

As an aside, this is where I think most baseball conditioning programs fail miserably; running poles falls right in this middle zone.

5. Thinking speed work had to be "all or nothing."

"Speed work" is one of the more hotly debated topics in the powerlifting world. I, personally, have always really thrived when I included it in my program. If you want to understand what it is and the "why" behind it, you can check out this article I wrote: 5 Reasons to Use Speed Deadlifts in Your Strength Training Programs.

A lot of people say that it's a waste of time for lifters who don't have an "advanced" level of strength, and that beginners would be better off getting in more rep work. As a beginner, I listened to this advice, and did lots of sets of 5-8 and never really focused on bar speed with lower reps. The end result? I was slower than death out of the hole on squats, off the chest on bench presses, and off the floor with deadlifts. And, it doesn't take much strength training knowledge to know that if you don't lift a weight fast, your chances of completing that lift aren't particularly good.

To the folks who "poo-poo" speed work, I'd just ask this: do you really think focusing on accelerating the bar is a bad thing?

Here's a wild idea, using bench presses as an example. If a lifter has a heavier bench press day and a more volume/repetition oriented day each week, what would happen if he did an extra 3-4 sets of three reps at 45-70% of 1-rep max load during his warm-up? Would that be a complete waste of time? Absolutely not! In fact, the casual observer would never even notice that it was happening.

The point is that speed work is easy to incorporate and really not that draining. You can still do it and get a ton of other quality work in, so there is really no reason to omit it. Having great bar speed will never hurt your cause, but not training it certainly can.

Looking to avoid these mistakes and many more - all while taking the guesswork out of your squat, bench press, and deadlift training? Check out The Specialization Success Guide. This comprehensive product to bring up the "Big 3" has been a huge hit; you can learn more HERE.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

I'm happy to announce to my new product - a collaborative effort with Cressey Sports Performance coach and regular EricCressey.com contributor Greg Robins - is now available. If you're looking to improve on the Big 3 - squat, bench press, and deadlift - this resource is for you! Check it out: www.BuildingTheBig3.com.

This resource includes three separate 12-week specialization programs to improve one of the "Big 3" lifts, and it's accompanied by a 140+ exercise video database and detailed video coaching tutorials on squat, bench press, and deadlift technique. To sweeten the deal, we've got two free bonuses available if you purchase this week at the introductory price.

“As a former international athlete, The Specialization Success Guide gave me the structure I needed to not only get back into form, but has put me on track to crush my previous PRs across the board. Currently squatting 565, benching 385 and deadlifting 620, I am stronger, more mobile, and happy to report that my only regret is not having started this program earlier. SSG has been a game changer for me and I am excited to see where it takes me next!”

Jake S.

Needham, MA

“The Specialization Success Guide is legit! This program is ideal for those who want to get stronger, put on lean muscle, and improve their major lifts. The simplicity makes the program easy to follow and the exercise video library ensures everything is done right. Within the simplicity of the program you will find specific details that will target weak areas of your lifts to get you closer to your goals.

“Prior to running the SSG, Greg had been writing my programs for a year and a half using the same principles and philosophies you will find in The Specialization Success Guide. Greg’s programing has helped me add over 50 pounds to my back squat and a recent PR squat of 420lbs (2.2x my body weight), and I will be closing in on a triple body weight deadlift soon thanks to insights from him and Eric – just as you’ll find in this manual on the Big 3.”

Dave R.

Seattle, WA

Again, this resource - which comes with a 60-day money-back guarantee - is only on sale at the introductory $30 off price this week, so don't miss out. Click the following link to learn more: www.BuildingTheBig3.com. |

| Read more |

|

We're excited to announce that Cressey Performance staff member and accomplished powerlifter Greg Robins will be delivering a one-day seminar on August 24, 2014 at our facility in Hudson, MA. This event is a great fit for lifters who have an interest in improving the squat, bench press, and deadlift - and may want to powerlift competitively.

Overview:

"Optimizing the Big Three" is a one-day seminar geared towards those looking to improve the squat, bench press, and deadlift.

Split into both a lecture and hands on format, the event will provide attendees with practical coaching on the technique of the classic power lifts, as well as valuable information on how to specialize movement preparation, utilize supplementary movements, and organize their training around a central focus: improved strength in these "big three" movements.

Furthermore, Greg will touch upon the lessons learned in preparation for your first few meets, to help you navigate everything from equipment selection, to meet-day logistics.

The value in learning from Greg is a matter of perspective. He has a wealth of knowledge, and experience stemming from various experiences as a coach and lifter. Greg will effectively shed light on how he has applied human movement principles, athletic performance modalities, and anecdotal evidence from working with a plethora of different populations to one main goal; optimizing the technique, health, and improvements in strength of amateur lifters.

Seminar Agenda:

8:30-9:00AM: Check-in/Registration

9:00-10:00AM: Mechanics, Technique, and Cueing Of the Squat, Bench Press, and Deadlift - In this lecture Greg will break down the biomechanics of each movement, how to optimize technique, and what to consider both as a coach and lifter in teaching / learning the movements.

10:00-11:00AM: Managing the Strength Athlete: Assessing and Meeting the Demands of the Lifter - Learn what demands a high amount of volume in the classic lifts puts on the body, how to assess for it in others and yourself, and what you can do to manage the stress associated with these demands.

11:00-11:15AM: Break

11:15AM-12:45PM: General Programming Considerations for Maximal Strength - Take a look inside Greg’s head at his approach to organizing the training of a lifter. Topics will include various periodization schemes, and utilizing supplementary and accessory movements within the program as a whole.

12:45-1:45PM: Lunch (on your own)

1:45-2:15PM: Preparing for Your First Meet - Based off his own experiences, and knowledge amassed from spending time around some of the best in the sport, Greg will share some poignant information on what to expect and how to prepare for your first meet.

2:15-3:30PM: Squat Workshop

3:30-4:45PM: Bench Press Workshop

4:45-6:00PM: Deadlift Workshop

Date/Location:

August 24, 2014

Cressey Performance,

577 Main St.

Suite 310

Hudson, MA 01749

Cost:

Early Bird (before July 24) – $149.99

Regular (after July 24) - $199.99

Note: we'll be capping the number of participants to ensure that there is a lot of presenter/attendee interaction - particularly during the hands-on workshop portion - so be sure to register early, as this will fill up quickly.

Registration:

Sorry, this event is SOLD OUT! Please contact cspmass@gmail.com to get on the waiting list for the next time it's offered.

About the Presenter

Greg Robins is a strength and conditioning coach at Cressey Performance. His writing has been published everywhere from Men's Health, to Men's Fitness, to Juggernaut Training Systems, to EliteFTS, to T-Nation. As a raw competitive powerlifter, Greg has competition bests of 560 squat, 335 bench press, and 625 deadlift for a 1520 total. |

| Read more |

|

Today's guest post comes from Greg Robins. For more information on group training at Cressey Sports Performance, click here.

Training larger groups of people, or athletic teams, often gets a bad rap. Quickly identifying the downfalls, many of us never explore the intangibles that make group training great.

For example, large groups foster all kinds of natural qualities between people. If you don’t see the overwhelming value in developing camaraderie, loyalty, accountability, and – dare I say, family – you’re missing a large part of what it means to make people feel and perform better.

There are two sides to every coin, and group training certainly falls short in some respects, for some individuals. However, I challenge you to reevaluate how you view the relationship between the group setting and the athlete or client.

Is group training a suboptimal format for training, or are certain people in a suboptimal position to undergo group training?

I would argue the latter.

Furthermore, if you are in disagreement with my assessment, maybe the question is this: if a person is willing and able to train under the obvious constraints of group training (my perspective being that they do not need individual attention and are mentally capable of embracing a social environment) then is it still the case that group training is a suboptimal format? Or, is it that the group training format on which you’ve shaped your opinion to needs to be elevated? In other words, how can we make the group training experience better?

Below, as a good place to start, I have compiled four strategies I use to optimize group training. Quick and easy, you can apply these right away and use them as reference. Enjoy!

1. Effective organization

Organization of a group training session is paramount to its success. If the sessions are clearly thought out, they leave little room for the chaos that often ensues in the mass organization of people.

Start with this concept: “format must fit focus.”

If you read my material, you know I like to have a clearly defined purpose in everything I do. That’s where you begin. What is the focus for your training session? Are you trying to teach new movements, build work capacity, dial in technique, or something else? Sure, these qualities all overlap to some degree, but you need to have an overarching rationale for the day’s training.

With that in mind, the format you choose for the training session should allow you to carry out that goal most advantageously. For example, you won’t have much success teaching someone a complicated new movement when they have 30 seconds to perform it. Instead, you’re better off using a format that allows people to stay with a movement long enough to receive repeated exposure to it – so think out the training parameters. Are intervals the right choice, or is something more along the lines of a workshop or open gym type organization a better approach?

Lastly, how does the session flow through the training space? Do people have to bounce around from one side of the gym floor to the other, or is it very easy to move around? Set up the training session to be ridiculously easy to follow. That means you have to consider where the equipment is, and where people will be at all times.

2. Command presence

Not everyone may be cut out to coach large groups of people. In order to do so effectively, you have to have to do two things, be in charge and communicate clearly. You don’t need to be loud and boisterous, but you can be. I, for one, am not the type to yell; in fact, I rarely raise my voice. That being said, I have had plenty of new group members tell me they were referred by “so and so,” who says I am a “drill sergeant” and whooping their butt into gear. To me, that’s perfect; I’m not being overbearing, but I am fostering an environment in which I am clearly in charge of what we are doing.

In order to be in charge, you need to be prepared, and you need to be heard. Being prepared is simply a question of taking the time to assess the variables and act accordingly. Being heard is about doing what is necessary to deliver a unified message to many individuals at once. That transitions nicely to our final two bulletpoints.

3. Develop context

Context is everything when you want people to learn something. Essentially, we learn by comparing something foreign to us to something we already know (Eric wrote about this in a similar context here). Therefore, the more context you can create, the easier it will be for people to make connections, especially in the faster pace of a group setting.

The first place to develop context is by actually getting to know the people you are instructing. Obviously, we need to know as much as possible about a person’s physical development. Doing so means we can choose wisely from movement and load selection standpoints. However, you cannot overlook getting to know who the person “is” as well. What do they do for work? What sports do they play? This information is gold when it comes to teaching them, as you can appreciate their point of view and help them view the challenge through their perspective.

Context can also be created. You can create context by introducing new movements and concepts slowly and well before they will be applied in a more intense fashion via training. My favorite time to do this is the warm-up. Use your warm ups to test the waters with different movements, as well as to introduce subtle cues to which they can relate later on. A simple glute bridge develops context for someone when you’re quickly instructing him or her to engage the glutes on a deadlift lockout, for example. These subtle cues can also be individualized, and triggered by general cues later on, as per my final point…

4. Create individual focus points

Recently, I attended a fantastic seminar with Nick Winkelman, and my mind was blown with the quality information he was presenting. In many instances, hearing him explain how he coaches helped me realize what I was doing well, not only what I could do better. This was very much the case in regard to developing individual focus points.

Developing individual focus points is HOW YOU PERSONALIZE GROUP TRAINING!

Pull someone aside and show him or her something they need to focus on, and then you can cue the entire group and have each member respond in their own way; that, my friend, will change the game completely. For example, one individual may need to work on better abdominal bracing to keep the spine neutral, while another person may need to create more upper back tension to not lose positioning. Pull them aside, help show them what “right” feels like and explain to them that when they hear “brace,” that is what they should be thinking. When you approach things this way, you can say one single word and have two people doing completely different things. It’s up to you to be creative with how you cue, but if you develop individual focus points, you will have people flourish in a group setting.

In closing, I challenge you to do two things. First, think about whether or not incorporating some group training might be a good idea for your approach. I think it’s a valuable tool that teaches people to be accountable to each other and boosts the sense of community. Second, if you have reservations on the quality of the training with group training, challenge yourself to deliver a better product to those who meet the criteria to participate by using some of the strategies above.

If you're looking to learn more about bootcamps at Cressey Performance, you can check us out on Facebook.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

My random thoughts on sports performance training always seem to be a hit with readers, so I figured I'd turn it into a series I update every month or two. Here are five thoughts that have been rattling around my brain, in no particular order:

1. Anyone who reads this blog regularly knows that we use a ton of positional breathing drills. If you'd like some example, just check out Greg Robins' post from a few days ago here.

With that said, one of the biggest mistakes we made when we starting integrating these drills was not encouraging a "reset" at the end of the full exhalation. Basically, when you cue an athlete to fully exhale, you want a count of 3-4 "one-thousand" before they inhale again. Effectively, this gives an athlete a chance to a) get familiar/comfortable with this less extended position and b) regulate breathing rate (to turn off sympathetic activity). I've also found that it slows athletes down a bit so that they're forced to focus on doing things perfectly, too.

2. One thing that drives me absolutely bonkers is when I see people opening their hands up while doing Turkish get-ups. First, the obvious: do you really want to hold a weight right over your face without gripping it? Second, there are so many remarkable benefits from just gripping something, most notably increasing reflexive recruitment of the rotator cuff. If anyone has a legitimate rationale for opening the hand with the kettlebell overhead, I'd love to hear it - but nobody has been able to justify it to me as of yet.

3. I just finished up Charlie Weingroff's new DVD set, Lateralizations and Regressions, and particularly enjoyed the section he devoted to the "packed neck." Back around 2008, it was a change I made with not only my own training, but also how we coached our athletes - and it's yielded profoundly positive results.

As Charlie pointed out, neck position impacts everything else in the body, particularly with respect to optimizing thoracic mobility and scapular control. I think that sometimes, people discount the importance of neck positioning when teaching beginners, assuming they can just teach it later on in a training plan. In my eyes, when you allow people to deadlift (or perform any lift) while looking up (instead of maintaining a neutral cervical spine with eyes straight ahead), you're really just giving them a faulty compensation pattern to reposition their center of mass. It's a cue that should be provided from day 1.

For more information on Charlie's new resource, click here.

4. If you train athletes who commonly experience shoulder and elbow concerns - including those who have had surgery - and you don't have a safety squat bar handy, you're missing out on a hugely important piece of equipment. When it comes to axial loading (bar on the upper back or anterior shoulder girdle), it's the bar we use more than any other - and it's saved my squatting career, as I have a shoulder issue that doesn't like back squatting.

They aren't cheap, but to me, if you deal with these types of athletes/clients often, it's an awesome investment, not an expense.

5. With the MLB Draft a few weeks away - and several Cressey Sports Performance guys expected to be selected early in the draft - one of the things I hear scouts talking about all the time is "projectability" - or where an athlete will be in the years ahead. This is especially important in a sport like baseball, where a player doesn't just quickly ascend to the highest level, as you would see in the NBA or NFL. Instead, players usually log several years of minor league baseball, and the overwhelming majority of them never even actually make it to the big leagues.

To that end, in terms of projectability, scouts are always looking for players who might make big jumps in pro ball - whether it's due to physical improvements, baseball-specific coaching, positional changes, or any of a number of other "windows of adaptation." When you think about it in this context, the ideal would be to find a kid who hasn't been involved in organized strength and conditioning programs, is weak and undeveloped, and hasn't received good baseball coaching. There's no place to go but up, right?

Well, the corollary to that is that these woefully underdeveloped kids are usually the ones who have the most wear and tear on their bodies. If they are throwing hard or demonstrating great bat speed, they've often spent years hanging out on passive restraints (e.g., ligaments) because the active restraints (e.g., muscles) haven't been sufficient to pick up the slack. In other words, they're injuries just waiting to happen. And, we know that having even just one surgery while in the minor leagues dramatically reduces a player's chance of making it to "The Show;" in face, one MLB strength coach told me that it reduced the likelihood of a player making it to the big leagues by 50%.

So, you could really say that projectability is a balancing act for teams. You want athletes who aren't completely tapped out physically, but at the same time, aren't so fragile-looking that you think they'll fall apart on you before you can even develop them. I think it's why a lot of scouts love to see multi-sport high school prospects; it automatically shows that they're "middle-of-the-road" athletes. They've got solid general athletic development and less wear and tear (because of no year-round baseball). Plus, they can pick up more advanced skills easier because they've expanded their motor learning pool with a wide variety of activities over the years. Coaching them once they're in pro ball is generally easier than it would be with a kid who's spent 12 months each year learning bad habits without ever wiping the slate clean for a few months. Plus, because they've played multiple sports, you know that they've learned to roll with different social circles - and playing professional baseball will certainly test their abilities to interact with a wide variety of people.

Just food for thought from a guy who's not a scout, but can't help but make observations from a pretty informed perspective.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Today's guest post comes from Greg Robins.

I have this weird habit. Although, the more I pick the brains of like-minded individuals the more I realize it’s just something everyone fascinated with human development does.

I like to watch people. I like to watch their curious reactions to their external environment. I like to watch people converse with other people. I like to watch how they move, how they breathe, how they settle into their default static positions. It sounds creepy, I guess, but it’s far removed from the image you have of me lurking in the window with binoculars.

I’ll watch sports and realize I’m no longer even keeping an eye on the ball; I’m lost in awe of the fluidity of an elite athlete’s movement capabilities. If I’m close up at a live sporting event, I’m analyzing the body type and physical development of players while they’re warming up.

I’m constantly looking at people, and conversing with people; trying to piece together who they are.

When Eric started this series I thought it was fascinating. It only made me more tuned in to the details of people, outside of any diagnostic tests I may eventually bring them through. Assessments became like an experiment of sorts. I would take all these clues from the first 20 minutes I met someone and see if the eventual tests gave some validity to the observations, and presumptions I was making.

I decided I had to contribute a one of my favorite assessments that you might be overlooking:

Hypertrophy and or tone of the accessory breathing musculature, coupled with primarily breathing through the mouth.

As I stated above, one thing I watch is how people breathe. However, even before I tune into watching individual breaths, I look at the muscularity and apparent tone of their accessory respiratory muscles. In particular, I’m looking at their neck. Often time people who are “stuck” in a faulty respiration strategy have necks that seemingly look to belong on a pro strongman, not a middle-aged weekend warrior, or an undertrained high school pitcher. Their scalenes, sternocleidomastoids, and levator costarum muscles are incredibly developed in comparison to the rest of their musculature. Bill Hartman posted a great video on this a few years back, if you'd like to see it in action:

This little tip off leads me to take a closer look at their respiration. I often notice the same person breathing primarily through the mouth, rather than the nose. I lay them on their back, have them remove their shirt (when appropriate) and cue myself in to the pattern of their inhalations and exhalations.

Not surprisingly these giants of neck development, are often the same folks who are stuck in inhalation, or a state of hyperinflation. They have poor function of their diaphragms, and generally take the form of our usual “over-extended” individual. In many cases, they present with a lack of shoulder flexion because their lats are constantly “on.”

They take shallow, frequent breaths, which never allow for full exhalation. To take a page out of the Postural Restoration Institute’s respiration manual, hyperinflation does the following:

- Increase sympathetic “fight or flight” responses and anxiousness

- Impairs nerve conduction

- Vasoconstricts peripheral and gastrointestinal vessels

- Restricts circulation in cerebral cortex

- Shunts blood flow peripherally

- Impairs coronary arterial flow

- Promotes fatigue, weakness, irregular heart rate, etc.

- Impairs breathing and weakens diaphragm contractility

- Increases overuse of “thoracic breathing”

- Enhances peripheral neuropathic syptoms

- Enhances sympathetic adrenaline activity and hypersensitivity to lights and sounds

- Increases phobic dysfunction, panic attacks, restless leg syndromes, heightened vigilance, etc.

- Facilitates catastrophic thinking and hypochondria

As you can see, this simple observation leads us to a series of additional questions, and more times than not, the discovery that someone’s ailments are the cause of their respiratory dysfunction. Their autonomics are dictating much of their dysfunction, even voluntary movement dysfunctions.

This is an important assessment because acknowledging this discord means we can intervene. Including breathing drills to correct respiratory function can help to restore many of the qualities we aim to improve (i.e. movement patterns, recovery rate, performance qualities, etc.).

If you are keen to excessive tone in the accessory musculature, you can begin to dig deeper and more closely observe their respiration, as well as ask them about different conditions listed above. If the pieces fit together, use some of the following drills to help them correct the dysfunction.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Here's this week's list of recommended strength and conditioning reading:

Cressey Performance Week at T-Nation - Three members of the CP staff had articles published at T-Nation this week. Greg Robins was up first, with Bench Press More in Four Weeks. Tony Gentilcore followed, with Building a Superhuman Core. Then, finally, I had an article published yesterday: How to Build Bulletproof Shoulders. Suffice it to say that I'm a very lucky guy to have such an awesome staff!

Elite Training Mentorship - In this month's update, I provided a presentation called, "20 Ways to Build Rapport on a Client's First Day." Additionally, I've got an article, as well as two exercise demonstrations - and this complements some great stuff from the rest of the ETM crew. Check it out.

10 Nuggets, Tips, and Tricks on Energy Systems Development - Mike Robertson wrote this last week, and I thought it was a fantastic look at some key points coaches need to understand with respect to "conditioning."

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Today's guest post comes from Greg Robins.

Planning the training of an athlete is mainly a question of considering variables. The success of a strength and conditioning program is largely the result of how well a coach can manage these variables, as well as the implementation of the training program.

In order to effectively begin the planning process, a coach must ask himself six questions: who, what, when, where, why, and how.

Many coaches instinctively weigh the answers to these questions in order to develop the training as a whole. I am no different. That being said, I recently watched a presentation from James Smith in which he organized common consideration into the familiar WWWWWH format. His acknowledgment of these considerations was the inspiration for this article, so thank you, James.

Who?

The first consideration must be the athlete with whom you’ll be working. Each athlete is different, and thus each athlete will need an individualized approach to his or her preparation. We are quick to label a program or exercise “sport specific,” but in reality, a good programs are exercise selection are “athlete specific.”

Are you planning the training of a male or female? What is the athlete’s age?

The sex of the athlete may call for different training parameters. The same is true of the athlete’s age, as well as the interaction of the two factors.

Furthermore, what are their movement or orthopedic limitations, and injury history? This is a huge question in both the terms of exercise selection and workload. This consideration will also affect the answer of subsequent questions. Not to jump ahead, but the “why” you are training an athlete can be greatly influenced by their limitations.

Lastly, who is the athlete from a preparation level? This question can lend itself to the “when” as well as the “how.” However, an athlete’s “identity” is largely a product of their preparation to date. What is their level of skill or sport mastery, general and specific work capacity, limit strength, explosive strength, and exercise technique?

What?

The main question here is, “what is the athlete’s sport?“

The training plan must aid an athlete in attaining a high level of sport mastery. Do you as the coach understand the parameters and demands of the athlete’s sport?

How do the improvements of different categories translate to the improvement of the athlete in their sport? The special work capacity of the soccer player differs greatly from that of the sprinter. Limit strength, for example, may hold a higher priority to the football player than the baseball player.

Also of consideration for some sports is the position or primary event of the athlete. Offensive lineman are a lot different than quarterbacks, and goalies have markedly different demands than midfielders. Obviously, this consideration weighs more heavily in some sports than others.

When?

Asking “when?” leads us to series of questions based on time.

When is the athlete’s competitive season, and when is the off-season? The answer to this question helps us to form an idea of the length of any training stages.

For example, a Major League Baseball season consists of spring training, plus 26 weeks and 162 regular season games, plus a possible 20 additional post-season games. In other words, a MLB player spends more time in the competitive season than he does in the off-season. Factor in a block for restoration from the competitive season, and you have very little time to actually prepare the athlete for the following season. Now, ask yourself the difference in the length of the competitive season for a minor league player, college player, and high school player? Each offers different lengths of time for the coach to prepare the athlete. Therefore, while each athlete’s training should be geared toward producing the best possible result on the field, each athlete will be able to spend different amounts of time on improving certain abilities.

Football, on the other hand, has a pre-season, plus a 17-week competitive season, and a possible additional 3-4 post-season games. The football player has considerably more time to prepare in the off-season.

Lastly, when will you be working with this athlete?

Will you have them for a few weeks, a single off-season, the next four years, or the next eight years? Furthermore, when will you be monitoring their training, and when will they be carrying out the training plan without your guidance?

These final answers MUST be taken into account when developing the strength and conditioning program of an athlete. A coach must train for the future, and knowing that you will influence an athlete for multiple years rather than multiple weeks greatly changes the approach.

Where?

Where are you receiving this athlete in their preparation and skill development timetable? While a coach may receive an athlete who has developed a high level of skill, they will not necessarily have a high level of physical preparation. The two are not linked.

Is this the first time ever dedicating any time to physical preparation as opposed to skill development?

Has the athlete acquired a high level of physical preparation, and lacks the skill development to move forward?

The answers to these questions will help you as the coach better determine the means, and minimal effective dose, for this athlete to make improvements to their game.

To back track, you must also ask yourself where the athlete is in relation to their competitive season. If you receive an athlete one week after the close of business, as opposed to one month before the start of business, the training focus must be in line with the plan, regardless of what you see them lacking in on a global scale.

One month before the competitive season is not the time to makes gain on maximal strength, even if that is a weak link. Moreover, one week after the competitive season is not the time to place a majority focus on skill development, regardless of the fact that an athlete may be greatly lacking in this quality.

Why?

This may be the single best question you can ask yourself as a coach. Why are you working with this athlete?

The answer to that question is the sum of all the questions you have asked yourself up to this point. On a general level, the answer is the same: to improve the athlete’s sport outcome.

The real question you are asking is on a far more specific level.

You are not working with a professional athlete for the same reason you are working with a freshman in high school. Additionally, you may not be working with professional athlete A for the same reasons you are working with professional athlete B.

Each athlete will produce different answers to the questions of Who, What, When, and Where. Therefore, the “why” is different in each athlete’s case, and the training must be tailored to that individual’s needs.

How?

How is the final question, and one that has many different answers. This is not an article on training philosophies, and so the answer to this question is different for each of you. That said, once you get to this final question, all pre-requisite variables have been established.

From here, you as the coach must form the training plan. How will you sequence the training, and what means, methods, amounts of volume, intensity, and frequency will you use?

In ending, qualified coaches will ask themselves these six questions before ever entering a single digit or exercise name into their template. Not doing so is to completely ignore the preparation process as a whole. Consider the training process on a much larger scale than just a single workout, or four-week phase. Instead, investigate where an athlete falls in the scheme of physical preparation and skill mastery on a career-long basis. Use the information gathered to enter the athlete into the proper phase of preparation and to focus the training to the needs of each athlete on an individual basis.

Looking for a program that helps you with individualization and takes the guesswork out of self-programming? Check out The High Performance Handbook, the most versatile strength and conditioning program on the market.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Today's guest post comes from Cressey Sports Performance coach, Greg Robins.

Hi, my name is Greg, and I have a problem.

I love the barbell.

In fact, I would be perfectly happy just training with the bar, a rack, a bench, and some plates. Call me crazy, but every exercise that has ever made a serious impact on my physique and strength levels involved the barbell.

To be honest, most people don’t use the bar enough. It’s not surprising, given the state of a typical “gym” these days. For every three or four bars, there must be a few hundred other pieces of equipment.

I continually challenge people to use the bar more often. Usually, my advice centers on doing more variations of the basic lifts. For me, the staple lifts never get old. However, I know plenty of people who thrive on variety in their training. With that in mind, here are five lesser-used exercises that include the barbell.

1. Barbell Rollouts

Rollouts are a great exercise, but not everyone has a wheel or other fancy implement. Not a problem! In fact, using a barbell is just as effective, if not more effective.

One benefit is that you can make the bar heavier or lighter. This may seem like a trivial difference, since the bar stays on the floor. However, you will notice that a 185-pound bar is a heck of a lot harder to pull back to the starting position. This will make your lats work harder, and tax your core. The best part? It makes your lats and abs work together, as they should!

)

2. 1-arm Barbell Rows

Heavy rowing should be a staple in most people’s programs, especially those of you who want to move some appreciable weight in the gym. This variation is a serious grip challenge. It’s also a great way to load up past what the gym offers in DBs; just use a strap so you can hold on. However you choose to do it, the basic premise is simple: perform a row in the same fashion as 1-arm DB row. In this case, keep the barbell between your legs, and make sure to use 10- and 25-pound plates so you can keep a decent range of motion.

3. Weighted Carries

Most folks look immediately to farmer’s handles, DBs, and KBs to do weighted carries. That’s all well and good, but the barbell lends itself very well to a few loaded carries as well. Among my favorites are a barbell overhead carry, a barbell zercher carry, and a 1-arm barbell suitcase carry.

Each offers a totally different advantage. Overhead helps people work anti-extension properties in full shoulder flexion. The Zercher carry is great as an anti-extension exercise as well, and a better choice for those who can’t get overhead safely. Lastly, the suitcase carry trains core stability in virtually every plane, and even challenges the grip quite a bit.

4. Self Massage

Forgot your PVC pipe? No worries! The barbell with a small plates on each hand can make for a roller as well. It’s not for the more tender individuals, but works perfectly fine for people who have a longer history doing self-massage.

I also like the fact that the bar is much thinner than a roller, putting more direct pressure on the areas of interest. Try this baby out on your lower extremities and lats next time you hit the gym.

5. 1-arm Overhead Exercises

I’ve written previously about the benefits of bottoms-up KB exercises. They create a lot more need for shoulder stability, and tax the grip. However, the barbell can offer a similar benefit.

Since the bulk of the weight is now further from your hand, the forearm and shoulder demands increase BIG time.

It’s a great challenge on 1-arm shoulder presses, as well as Turkish Get Ups. Don’t believe me? Give it a try.

If you’ve been hunting down some new physical challenges in the gym, these should definitely get you moving. Train hard and use the barbell!

Greg will be presenting his popular "Optimizing the Big 3" training workshop at Cressey Sports Performance in Massachusetts on August 2. This event is a great fit for lifters who have an interest in improving the squat, bench press, and deadlift - and may want to powerlift competitively. And, it's also been very popular with strength and conditioning professionals. For more information, click here.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|