|

As you’ve probably already noticed, it’s been a bit quieter on the blog of late. Normally, I try to get up at least two – and usually three – new posts per week. Over the past few months, it’s been more like 1-2 posts.

With two facilities in two states – and a pair of two-year-olds at home – life has a very brisk pace to it right now. The baseball off-season keeps me very busy, so when October through February rolls around, some things just have to take a back seat. For me, that’s usually writing and traveling for speaking engagements. In-person coaching is what I love, and this is the absolute best time of year for it.

Fortunately, though, it doesn’t have to be “either/or” for me; rather, it can be “and” if I select a convenient medium. To that end, I’ve done more video content on the social media front with my 30 Days of Arm Care series and some random videos of our pro guys training.

Right now, I’m prioritizing the most time-sensitive demands (in-person training), particularly because they’re the part of my professional responsibilities that I love the most. And, obviously, it’s a goal to prioritize family time above all else, and I need to get my own training in.

Simultaneously, while I’d much rather write detailed content and film longer videos, it’s not always feasible – so I’ve conceded that some quick social media posts and even the occasional guest contribution from another writer are solid ways to keep the ball rolling in the right direction with my online brand while I manage the pro baseball off-season.

As I thought more and more about this time crunch conundrum, it goes me to thinking about how it parallels what folks deal with on the training front. Two key principles – prioritization and concession – really stand out in my mind.

The best training programs are the ones that clearly identify and address the highest priorities for the lifter. If a 14-year-old kid can’t even execute a solid body push-up, putting him on a 3x/week bench press specialization program probably isn’t the best idea. Likewise, if a 65-year-old women can’t even walk from the car to the gym without back pain, she probably shouldn’t be learning how to power clean on her first day. These prioritization principle examples might seem obvious, but not all scenarios are as clearly defined. There are loads of factors that have to be considered on the prioritization front once someone has more training experience: duration of the window to train (off-season length), injury history, personal preferences, equipment availability, etc. It’s not always so black and white.

If you’re going to prioritize, it invariably means that you have to concede; very simply, you can’t give 100% to absolutely everything. If you go on a squat specialization program, you need to concede that you’re going to train your deadlift and bench press with less volume/intensity and later in your training sessions. Not everything can be prioritized all the time because of our limited recovery capacities.

Looking back, while I didn’t realize it at the time, these two principles help explain some of the popularity of my High Performance Handbook. By giving individuals various options in terms of both lifting frequency (2x/week, 3x/week, and 4x/week) and supplemental conditioning protocols, it afforded them the opportunity to prioritize and concede as they saw fit while still sticking to the primary principles that drive an effective program.

Additionally, because they were the ones selecting which route to pursue, it gave them an ownership role in the training process. My good friend (and Purdue Basketball Strength and Conditioning Coach) Josh Bonhotal went to great lengths to highlight how important this is to the training process in this article. I love this quote in particular:

As I wrap my head around this even more, it makes me realize that when we educate an athlete about prioritization and concession - usually in the form of a thorough evaluation where we demonstrate that we want to individualize our programs to their needs - we're empowering them as part of the decision-making process. And that's where "buy-in" and, in turn, results follow.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Everyone on the planet is having a Black Friday sale this week, so we figured we wouldn't even attempt to keep you in suspense on this one. With that in mind, you can save 20% on the following products through Cyber Monday at midnightk by entering the coupon code BF2016 (case sensitive) at checkout. Just click on the links below to learn more and add them to your cart:

Functional Stability Training: Individual Programs or a Bundle Pack

Optimal Shoulder Performance

Understanding and Coaching the Anterior Core

Everything Elbow

The Ultimate Off-Season Training Manual

The Specialization Success Guide

The Art of the Deload

Again, that coupon code is BF2016.

Additionally, my products with Mike Robertson are on sale, too. You can pick up Assess and Correct, Building the Efficient Athlete, and Magnificent Mobility for 20% off (no coupon code needed) HERE.

Enjoy - and thank you for your support!

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

I figured it'd be a good time to add another installment to this series, as today is the last day of the sale on The Specialization Success Guide. Through midnight tonight (Sunday), you can save 40% by entering the coupon code ROBINS at checkout HERE.

Here are six strategies to help you in your strength pursuits:

1. Be a beltless badass.

My wife has a very good deadlift for someone who's never competed in powerlifting; she's pulled close to 300 pounds, which is about 2.5 times her body weight. What's most impressive to me, though, is that even when she gets up to 95-100% of her best deadlift, her form never breaks down. This has a lot to do with consistent coaching early on, and the right pace to progressions over the ten years I've known her.

That said, I also think that it has a ton to do with never wearing a lifting belt. Seriously, she has never put on one. Likewise, I have athletes who have been with us for close to a decade who have never worn one, either. I'm a big believer:

[bctt tweet="Optimal long-term technique and strength success is built on a beltless foundation."]

Interesting, on this point, I reached out to Tony Bonvechio, and he said that most of his novice lifters will gain about 20% on their squat and deadlifts by wearing a belt.

Conversely, Tony himself gets about 9%, and I'm slightly less than that (6-7%). I reached out to some very accomplished lifters, and after crunching the numbers between raw and belted PRs, none of them were over 10% difference.

To this end, I think a big training goal should be to reduce the "Belt Deficit." Training beltless is a great way to make sure that "ugly strength" doesn't outpace technique in beginning lifters, and it can also be a hugely helpful training initiative for more advanced lifters who may have become too reliant on this implement.

2. Don't be afraid to gain some weight.

Make no mistake about it; you can improve strength without gaining weight. It can, however, be like trying to demolish a 30-story building with an ice pick instead of dynamite.

I've had some success as lightweight (165-181-pound class) lifter, but this can be misleading because there have been multiple times in my lifting career when I've pushed calories to make strength gains come faster. In the fall of 2003, for instance, I went from 158 up to 191, and then cut back to a leaner 165. In the summer of 2006, I got up to 202, then back down to the mid 180s. These weight jumps made me much more comfortable supporting heavy weights in the squat and bench press, as a little body weight goes a long way on these lifts.

3. Learn to evaluate progress in different ways.

Traditionally, powerlifters have only cared about evaluating progress with the "Big 3" lifts. Unfortunately, those aren't going to improve in every single training session. To some degree, the Westside system of powerlifting works around this by rotating "Max Effort" exercises - but even with rotating exercises, it's still an approach that relies on testing maximal strength on a very regular basis. Occasionally, it'll lead to disappointments even over the course of very successful training cycles.

For this reason, we always encourage individuals to find different ways to monitor progress. Tracking bar speed can be great, whether you have technology to actually do it, or you're just subjectively rating how fast you're lifting. A lower rating of perceived exertion (RPE) at a given weight would also indicate progress.

Volume based measures are also useful. Hitting a few more reps with the same weight during your assistance work is invaluable; those reps add up over the course of a longer training cycle. Also, making a training session more dense (more work in the same or less amount of time) can yield great outcomes.

Looking for more strength strategies or - better yet - programs to take the guesswork out of things for you? Check out The Specialization Success Guide, a resource for those specifically focused on improving the squat, bench press, and deadlift.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Today's guest post - the first in a new series - comes from Greg Robins.

It’s been a while, and oh how I have missed the electronic pages of EricCressey.com. Quick and Easy Ways To Feel and Move Better was fun, but after 50+ editions, I needed something new.

To piggyback off the idea of quick useful, intelligent tips, I have decided to create a fresh new look. This time around I have decided to speak to the strength-training enthusiast in particular. In short, this new series will be devoted to those in the crowd who are most concerned with – above all else – getting stronger.

My aim is to keep this easy-to-apply and simple strategies to help you get stronger. I will organize each week into four categories, or “pillars of success” in the gym. They are mindset, planning/programming, nutrition/recovery, and technique (via a quick instructional video or photos).

Given that this is the first installment, I figured we’d start of with a BANG, so here are two in each category.

1. Mindset: success in strength training takes sacrifice.

I’ve been fortunate enough to reach many of my own goals, but also to spend time around others who have had tremendous success in their chosen endeavors. The list includes CEOs, professional athletes, entrepreneurs, elite level strength athletes, physique competitors, decorated military leaders, and a host of other “successful” individuals. There are a plethora of commonalities among these people, but the one I want to focus on is the extraordinary amount of sacrifices these people make to accomplish their goals.

To be frank, none of us will attain the strength measures we want, the body we want, or the life we want without making sacrifices. While some may be afforded a hand-up, nobody who truly reaches an admirable level of success receives a hand-out (kudos to my girlfriend for introducing me to the hand-up vs. hand-out analogy).

If you want to do something out of the ordinary, you will make sacrifices on a daily basis that separate you from the majority of people. If what you wanted to achieve was doable by simply going through motions, showing up, and following the masses, it would not be considered extraordinary. I suppose this is common sense., but let’s face it: common sense isn’t so common anymore.

The real advice here is that one must be aware of why they are making sacrifices. Why are you choosing to get to bed rather than to watch the late night game? Why are you choosing to have one beer instead of seven? Why are you leaving early to make sure you can grab groceries before the store closes? As it is so commonly put, what is your why? Lose site of this and sacrifices become tedious chores, your goals become your master, and your life one of self-inflicted servitude. Choose instead to keep yourself focused on the goal.

2. Mindset: selfishness is a rather darker, but necessary, quality of the perennially strong.

There are a few darker truths to reaching uncommon heights. One of them happens to be one I mull around with in my head quite a bit. The truth of the matter is that in order to take extremely good care of oneself requires a degree of selfishness. In order to continually make progress, one must continually find ways to improve upon what they’re already doing. In terms of strength training, one must continue to train at a higher level in some capacity. This also means they must recover at a higher level. Training at a higher level may mean that more focus need be placed on the training sessions, including spending money on equipment or coaching, traveling further, staying longer, and so on.

In terms of recovery, it most definitely means finding ways to reduce outside stressors, improve sleep, and dial in nutritional measures. Put in various situations, without enough regard for what YOU want, the aforementioned things will not happen often enough.

How often do we tell people with poor health to care for themselves more – to essentially put themselves, and their needs first, more often? At a much smaller level we are acknowledging that the health and vitality we want them to achieve will take some selfishness. It would be wrong to imagine that if someone wanted to achieve higher than ordinary levels of health and performance, it wouldn’t take more selfishness…because it will. It’s a darker truth, but one you can learn to communicate and help others understand so as not to appear to be merely self involved.

3. Planning and Programming: regulating on the fly.

Many informed gym goers have become savvy on following programs, utilizing technology to monitor readiness, and simply finding every way possible to “optimize” the training process. I must say, of all the strongest people I have ever been around, watched, read about, looked up to, none seem to rely on said measures.

Instead they understand the basic principles of training. When you understand the basics well – very well – you will be able to see the forest through the trees. When you see the big picture, regulating training on the fly isn’t over complicated.

Here’s a good place to get started:

You need to do more than you did last time. That’s the basic premise anyhow. With that, a plan can be formed by looking at the past training and improving on it. At a certain point, weight cannot be continually added to the bar in the same fashion. Therefore, training will revolve around two kinds of sessions. The first is geared toward the amount of weight on the bar. The second is either on the speed the weight moves, and or the amount of times weight is moved.

In any plan, there will be times when things don’t go as planned. At those times, simply keep in mind what the purpose of the training is. If the goal was to move a certain load, and you can’t do it for the planned amount, move it less times that day. If the goal was to move it fast and it’s slow, adjust to a weight you can move fast. If the goal was to move it a certain amount of times, lower the load, and move it the required amount of times.

4. Planning and Programming: unilateral stability is not limited to single-leg exercises.

Single-leg exercises are great if you want to get strong at single-leg exercises, or have some limitation that keeps you from doing bilateral exercises. Why would someone want to get strong on single-leg exercises? Pretty much for every reason possible, unless their overriding goal is to be extremely good at bi-ateral exercises! Simply stated, too much attention and energy must be given to these exercises in order to get them brutally strong that could otherwise be spent getting better on two legs, if that is your goal.

Single-leg stability, which for the sake of this tip I will differentiate from single-leg strength, is something everyone should posses. We do, after all, function in split-stance positions, kneeling positions, and on one leg all the time.

You do not need to do lunges, split squats, step-ups and so forth in order to gain acceptable levels of single-leg stability. This is good news for the squat and deadlift enthusiasts. You will want to keep a good level of unilateral stability so instead just focus more of your accessory exercise choices on movements that test single-leg stability. Examples include half-kneeling and split-stance anti-rotation presses, chops, and lifts, for starters.

Other ideas include carrying variations, and even simple things like low level sprinting, and – dare I say – walking more!

5. Nutrition: eat carbohydrates.

To my own detriment, I spent most of my lifting career still strapped in for the low-carb ride. That was really a big mistake. I initially saw great physique changes when I adopted a low carb approach, and thus I turned to it all the time. However, the truth is that what I really did was stop eating too much processed crap, and eating too much in general.

Carbohydrates are the fuel your body wants be a powerful machine. Simply put, fuel appropriately for the demand you are placing on it. If your goal is to be bigger, stronger, and faster, don’t trade in your oatmeal for a buttered-up coffee.

That said, if your training is sporadic and uninspired, and your life outside of the gym mostly sedentary, then by all means, watch the carbohydrates. If you are training 4+ days each week and trying to progressively push the limit of what you can do, eat more carbohydrates.

6. Nutrition: invest in a rice cooker.

To build off my last point, I prefer to keep my carbohydrate sources as “real” as possible. I won’t lie, I like a good bowl of cereal, and cornbread is something I could easily live on. The majority of the time I stick to five major sources of carbohydrates, and while I’ll divulge them all eventually, the first one is jasmine rice. It tastes better, digests easier, and has a better consistency than any other rice I have tried. I easily consume upward towards 8 to 10 cups of it (dry measure) in a given week. That translates to a lot more cooked. And, on that note, I wouldn’t be nearly as excited about rice if I didn’t have a rice cooker.

This simple gadget will run you anywhere from $15 to $30 and is well worth it. Simply add one part rice to two parts water, press the button, and prepare the rest of your food in the 10 minutes it takes to cook. If that’s too hard for you, then there’s no hope for you as a chef. If you’re someone who struggles to put on size, make the rice cooker as routine as making coffee each morning. I’m willing to bet an added cup or two of rice to your normal intake will have you started back in the right direction.

7. Technique: keep the armpits over the bar.

8. Technique: understand the difference between flexion/extension movements and flexion/extension moments.

Additionally, if you need some programming guidance to prioritize the squat, bench press, or deadlift, check out our collaborative resource, The Specialization Success Guide.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

It goes without saying that the bench press is one of the "Big 3" lifts for a reason: it offers a lot of bang for your upper body training buck. That said, the close-grip bench press is an awesome variation, as it can be more shoulder-friendly and offer slightly different training benefits. Unfortunately, a lot of lifters struggle to perfect close-grip bench press technique, so I thought I'd "reincarnate" this video I originally had featured on Elite Training Mentorship. Enjoy!

If you're looking for a more detailed bench press tutorial - and a comprehensive bench press specialization program - I'd encourage you to check out Greg Robins and my new resource, The Specialization Success Guide.

Have a great weekend!

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

It's time for this month's sports performance training musings. Many of these thoughts came about because we have a lot of our professional baseball guys back to kick off their off-season training, so I'm doing quite a few assessments each week. In no particular order...

1. There is a difference between "informative" assessments and "specific" assessments.

I recently spoke with a professional baseball pitcher who told me that his post-season evaluation included a 7-site body fat assessment, but absolutely no evaluation of scapular control or rotator cuff strength/timing. Skinfold calipers (especially in the hands of someone without a ton of experience using them) are hardly accurate or precise, but they can at least be "informative." In other words, they tell you something about an athlete.

However, I wouldn't call a body fat assessment a "specific" assessment. In other words, it's really hard to say that "Player X" is going to get injured because his body fat is 17% instead of 15%.

Conversely, we absolutely know that having poor scapular control and rotator cuff function is associated with a dramatically increased risk of injury in throwers. Checking out upper extremity function is a "specific" assessment.

This example, to me, illustrates why good assessments really are athlete- and sport-specific. Body fat assessments mean a lot more to hockey players than they do to baseball players, but nobody ever attributed a successful NHL career to having great rotator cuff strength.

Don't assess just for the sake of assessing; instead, assess to acquire pertinent information that'll help guide your program design to reduce injury risk and enhance performance.

2. Extremes rarely work.

Obviously, in a baseball population, most athletes have at least some kind of injury history. It's generally a lot of elbows and shoulders, but core and lower extremity injuries definitely show up on health histories. When I see these issues, I always try to ask plenty of questions to get a feel for what kind of training preceded these injuries. In the majority of cases, injuries seem to come after a very narrow focus - or specialization period.

Earlier this week, I saw a pro baseball guy with chronic on-and-off low back pain. He commented on how it flared up heavily in two different instances: once in college, and the second time during his first off-season. In both cases, it was after periods when he really heavily emphasized squatting 2-3 times per week in an effort to add mass to his lower body. Squats were the round peg, and his movement faults made his body the square hole. Had he only squatted once a week, he might have gotten away with it - but the extreme nature of the approach (high volume and frequency) pushed him over the edge.

I've seen command issues in pitchers who threw exclusively weighted balls, but rarely played catch with another human being. I've seen plenty of medial elbow discomfort in athletes who got too married to the idea of adding a ton of extra weight to their pull-ups.

General fitness folks, powerlifters, and other strength sport athletes can get away with "extreme" specialization programs. Heck, I even co-created a resource called The Specialization Success Guide!

However, athletes in sports that require a wide array of movements just don't seem to do well with a narrow training focus over an extended period of time. Their bodies seem to crave a rich proprioceptive environment. I think this is why "clean-squat-bench press only" programs leave so many athletes feeling beat-up, unathletic, and apathetic about training.

3. Consider athletes' training experience before you determine their learning styles.

I'm a big believer in categorizing all athletes by their dominant learning styles: visual, kinesthetic, and auditory.

Visual learners can watch you demonstrate an exercise, and then go right to it.

Auditory learners can simply hear you say a cue, and then pick up the desired movement or position.

Kinesthetic learners seem to do best when they're actually put in a position to appreciate what it feels like, and then they can crush it.

In young athletes and inexperienced clients, you definitely want to try to determine what learning style predominates with them so that you can improve your coaching. Conversely, in a more advanced athlete with considerable training experience, I always default to a combination of visual and auditory coaching. I'll simply get into the position I want from them, and try to say something to the point (less than ten words) to attempt to incorporate it into a schema they likely already have.

This approach effectively allows me to leverage their previous learning to make coaching easier. Chances are that they've done a comparable exercise - or at least another drill that requires similar patterns - in previous training. As such, they might be able to get it 90% correct on the first rep, so my coaching is just tinkering.

Sure, there will still be kinesthetic learners out there, but I find that they just aren't as common in advanced athletes with significant training experience. As such, I view kinesthetic awareness coaching as a means to the ultimate end of "subconsciously" training athletes to be more in tune with visual and auditory cues that are easier to deliver, especially in a group setting.

4. Separate training age from chronological age.

This can be a difficult concept to relate, so I'll try an example.

I have some 16-year-old athletes who have trained with us at Cressey Sports Performance for 3-4 years and have great anterior core awareness and control. I'd have no problem giving them the slideboard bodysaw push-up, which I'd consider a reasonably advanced anterior core and upper body strength challenge that requires considerable athleticism.

Conversely, I've had professional baseball players in their mid 20s who've shown up on their first day with us and been unable to do a single quality push-up. The professional athlete designation might make you think that they require advanced progressions, but the basics still work with the pros. You might just find that they picked things up quicker - and therefore can advance to new progressions a bit more rapidly than the novice 13-year-old.

Quality years of training means a lot more than simply the number of years a young athlete has been alive, so make sure you're working off the right number!

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

In light of the recent launch of The Specialization Success Guide, I feel like there have been a lot of posts on the site lately on the topic of powerlifting. With that in mind, I thought I'd shuffle things up with a bit more discussion about training in a broader sense, so let's talk some general athletic development.

1. We don't any regular barbell bench pressing with our baseball guys, and it's even pretty rare for us to use dumbbell bench pressing in their programs. This is, in part, because we want to utilize movements where the scapulae can move freely, as opposed to having them pinned down on a bench. In light of this exclusion, we're often ask: what do you do instead?

The answer, as many of you know, is landmine presses, push-up variations, and cable press variations. However, what a lot of people might not realize is that another good option is to simply replace a press with some kind of overhead hold variation, whether it's a Turkish get-up or bottoms-up carry.

One other variation I really like is the kneeling overhead hold to stand. I'll often use this with beginners who might need a little stepping stone before they get to the Turkish get-up. In addition to getting some great reflexive rotator cuff work, we're driving scapular upward rotation in a population that really needs it. Still, that doesn't mean that everyone is ready for it. Watch the video to learn more:

2. It's not uncommon at all to see medial (inside) elbow pain in lifter.s This usually comes from the tremendous amount of grip work one does in combination with lots of loaded elbow flexion. Usually, when these issues pop up, cutting back on lifting volume and modifying exercise selection is imperative.

However, what a lot of folks fail to appreciate is the impact that supplemental conditioning work can have on the overuse pattern. Just imagine how much abuse your common flexor tendon is taking when you hop on the rowing machine for 20 minutes to log a few thousand meters, or add in some barbell or kettlebell complexes. These are very grip-intensive approaches and need to be incorporated carefully - and certainly not all the time. Cycle them in, and then cycle them out.

As an example, I'm someone who deals with medial elbow irritation here and there, and most of the time, it's when I'm doing more work on the rower. As such, I've learned that one rowing session a week is really all I can handle if I'm doing my normal upper body training workload.

3. Having a good hip hinge is a huge contributor to athletic success, and to that end, we include toe touch progressions with a lot of our athletes. Without a doubt, the biggest mistake I see with athletes doing a toe touch is the substitution of knee hyperextension for hip flexion. Here's what that looks like:

You'll notice that there really is absolutely no posterior shift of the center of mass, and he stays in plantarflexion (calves don't stretch). This is something you'll see really commonly in athletes with very hypermobile joints. I've demonstrated it before with the following video; you'll notice that this loose-jointed athlete can actually get a crazy toe touch without any sort of hip hinge, as he's blocked by the wall. Hypermobile athletes will always try to trick you!

Every time you allow them to use a faulty hip hinge pattern, you're giving them two opportunities to work themselves closer to an ACL injury. First, you're putting them in a position where the glutes can't control the femur, and where the hamstrings are too overstretched to really help stabilize the knee effectively. Second, knee hyperextension is commonly a part of the typical ACL injury mechanism (especially in contact injuries where an opponent tackles an athlete low); do we really want to be going to this dangerous end-range over and over again in our training? With that in mind, when coaching the hip hinge, you want to ensure that the athlete establishes and maintains a slight bend in the knee; the "soft knees" cue usually works well.

4. I've often heard people talk about how prone bridges (front planks) are useless if you can already do quality push-ups. While I can certainly appreciate this line of reasoning, I think it overlooks two things.

First, most people rattle through push-ups pretty quickly, so the time under tension may actually be considerably lower than what one would get on a prone bridge.

Second, you can make a prone bridge considerably more difficult via a number of different means, and my favorite is adding full exhalations on each breath. This is something that's very difficult to "sync up" with push-ups, but the benefits are excellent: more serratus anterior recruitment, better posterior tilting of the pelvis, better anterior core engagement, and relaxation of overused supplemental respiratory muscles.

So, don't rule out bridges just yet! I love them as a low-level motor control exercise at the end of a training session - and after the loaded core work (chops, lifts, etc) have been completed.

Have a random thought of your own from the past week? Feel free to post it below; I'm all ears!

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

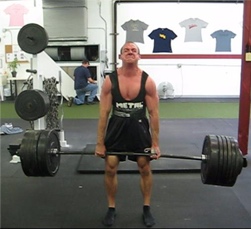

Yesterday, I deadlifted 600 for three reps for the first time. This is a number I've been after for quite some time.

After the lift, I got to thinking about some good lessons I could "teach" in light of this milestone for me. Here are five quick Saturday morning thoughts:

1. Personal records sometimes happen when you don't expect them.

I honestly didn't feel particularly great when I started the training session yesterday. In fact, if you'd asked me prior to the lift if I was going to be setting a PR in the gym that day, I would have said, "Absolutely not." However, a thorough warm-up and a few extra sets of speed deadlifts on the "work-up" did the trick. Make sure to never truly evaluate where you stand until you've actually done your warm-up.

2. It's really important to take the slack out of the bar.

If you watch the video above, you'll notice that I pull the bar "taut" before I ever really start the actual lift. Every bar has a bit of slack in it, and you want to get rid of it early on. Check out this video on the subject:

You can actually get a feel for just how much slack there is in the bar if you observe how much it bends at the top under heavy weights. This doesn't happen to the same degree with "regular" barbells.

3. Don't expect to accomplish a whole lot in the training session after a lifetime PR on a deadlift.

Not surprisingly, heavy deadlifting wipes me out. Interestingly, though, it wipes me out a lot more than heavy squatting. From a programming standpoint, I can squat as heavy as I want - and then get quality work in over the course of the session after that initial lift. When the "A1" is a deadlift, though, it's usually some lighter, high-rep assistance work - because I mostly just want to go home and take a nap after pulling any appreciable amount of weight!

4. Percentage-based training really does have its place.

For a long time, I never really did a lot of percentage-based training for my heavier work. On my heavy days, it was always work up, see how I felt, and then make sure to get some quality work in over 90% of my 1RM. As long as I was straining, I was happy. Then, I got older and life got busier - which meant I stopped bouncing back from these sessions as easily. Percentage-based training suddenly seemed a lot more appealing.

I credit Greg Robins, my co-author on The Specialization Success Guide, with getting me on board the percentage-based training bandwagon. He was smarter than me, and didn't wait to get old to start applying this approach when appropriate.

5. You've got to put force in the ground.

This is a cue I've discussed at length in the past, but the truth is that I accidentally got away from it for a while myself. Rather than thinking about driving my heels through the floor to get good leg drive, it was almost as if I was trying to "just lift the bar." It left me up on my toes more than I wanted, and my hamstrings got really cranky.

I took a month to back down on the weights and hammer home the heels through the floor cue with speed work in the 50-80% range, and it made a big difference. I've got almost 15 years of heavy deadlifting under my belt, and even I get away from the technique that I know has gotten me to where I am. Technical improvement is always an ongoing process.

Looking for even more coaching cues for your deadlift technique? Definitely check out The Specialization Success Guide. In addition to including comprehensive programs for the squat, bench press, and deadlift, it also comes with detailed video tutorials on all three of these "Big 3" lifts. And, it's on sale at the introductory $30 off price until tonight at midnight. Check it out HERE.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

Today's guest post comes from CSP Coach Greg Robins, who is my co-author on the resource, The Specialization Success Guide: 12 Weeks to a Bigger Squat, Bench Press, and Deadlift. It's on sale through tomorrow (Sunday) at midnight; just enter the coupon code ROBINS at checkout to get 40% off.

I realize that competing in powerlifting is a far cry from what most aspire to do. That being said, much can be learned from the approach, and much of what the general gym-goer is looking to accomplish can be reached with the help of a powerlifting program.

To be honest, when I began training alongside a few competitive lifters, competing was not even a thought in my mind. To this day, I don’t consider myself first and foremost a “competitive lifter.” I am a coach, and powerlifting simply has done the following positive things for me. I have seen it do the same for countless other people, and so I invite you take a gander, and ask yourself if you aspire for a similar outcome.

1. It teaches you the difference between “training” and “working out.”

Simply stated, if your visits to the gym don’t serve to attain a greater result in some physical endeavor, then you are simply “exercising.” Diving into a powerlifting program gives your visits to the gym a purpose. When you have a purpose for what you do, you are “training,” not “working out.“

When you make the switch, a few essential characteristics of the successful gym goer begin to emerge. For starters, you become more consistent. Knowing that each session builds off the last makes you more accountable to each training session. Consistency is the absolute must-have ingredient to accomplish any goal.

With that in mind, you ultimately become more accountable to yourself. Recovery measures like sleep and nutrition no longer become a tedious chore. Instead, you willingly make the decision to eat right, get adequate sleep, and minimalize activities that may take away from your training.

When those things organically start happening, you become more productive, see more results, and all the while never feel like they are anything but part of your way of lifes.

2. It teaches you about managing variables and gives you a consistent measurement for improvement.

The problem with most gym-goers is that they have no idea what is working, what isn’t working, or even what they are using to measure their success. Following a powerlifting program gives you three fundamental lifts from which you can measure progress. It’s cut and dry: are the numbers going up? If not, you can look back on your training and assess a few possibilities for why your strength isn’t improving. If yes, you can make note of what you are doing as a source of information to look back on should you run into a plateau down the road.

Over time, consistently working on the same end goal helps you to understand the training process as a whole. You will be able to take ownership for your plan, and optimize it for you.

3. Getting stronger just so happens to do a lot of good things for your physique, health, and lifestyle.

I’m not clueless; I know why most folks exercise. You can feed me all the lines about health, but the fact is most people just want to look good. I was no different. If I could go back in time, I would have started training like a powerlifter at age 16. If I had, I would have acquired everything I sought out from an aesthetic standpoint a LOT SOONER. When I began powerlifting, I obviously began to get a lot stronger – but I also ate better, slept more, and kicked bad habits that didn’t help my performance to the curb.

Not surprisingly, getting stronger meant I put on more muscle, eating better meant I actually got leaner, and paying attention to how my lifestyle did or did not support my training meant I was actually healthier, more productive, and just generally feeling more awesome.

I realized that looking and feeling good were just a bi-product of training with a purpose. My outlook changed, and I wasn’t caught up in superficial crap, just in paying my dues in the gym and earning my progress.

4. The powerlifting community brings out the best in the industry.

When you begin to train for the “Big 3,” you begin to enlist the help of others who do the same. You read their articles, watch their videos, attend their seminars, and so on. Maybe I’m biased, but those who put the time under the iron – and instill that mindset in others – are the people I have come to admire the most.

It’s really not surprising to me at all. Powerlifting taught me what was important. It taught me about movement, because I had to optimize my positions in each lift. It taught me about programming, because I had to be able to objectively look back on all my training variables. It taught me about delayed gratification, because strength takes time to develop. It taught me about work ethic, because nothing comes easy in the battle of forcing adaption. Again, it taught me about what is important, because I began to only concern myself with things that had positive influences on my development. It has done the same for others who share in the pursuit of strength and they are among the best people to learn from and be around.

When you take on this identity to your training, you become part of that community.

5. It instills a sense of confidence in you that is unparalleled.

Walk around and look at the state of this country. It can be appalling. Exercising, in general, may make you feel like you aren’t wasting away, but possessing a level of physical strength far higher than the normal person makes you feel like the specimen you are.

I’m all about using powerlifting as an outlet for my aggression, my need to push the levels of what I can do, to channel my inner animal, to overcome. To some, that notion is unappealing; it’s too “meatheadish”, or too primal. I beg to differ, completely.

In fact, through purposeful training I am more confident to share how I feel, to learn about anything and everything, to explore different avenues of self-development.

A well-defined training goal gives you an opportunity to willingly make yourself uncomfortable. In doing so you learn that even in times of adversity, or pain, that you did not choose to encounter you can get through. I walk around with a sense of confidence, not because I can lift a certain number of pounds, but because I can welcome a challenge head on, and crush it.

Can other forms of physical activity do something similar? Sure they can, but if you are part of the herd of gym-goers that walks into the gym each day and doesn’t know exactly why you there, and what the focus is for that day, then I challenge you to give a powerlifting-geared approach a shot.

You can pick up several 12-week training programs in The Specialization Success Guide that Eric and I developed, or you can dive into any other number of programs out there. I don’t care what you choose to do, but I do challenge you to see it through for a prolonged period of time. I welcome you to this community of like-minded individuals, and for those of you who do choose to run our program I thank you and look forward to hearing about your success.

For more information on The Specialization Success Guide - which is on sale through this tomorrow night at 40% off the normal price - click HERE. Just enter the coupon code ROBINS at checkout to receive the discount.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

With the release of The Specialization Success Guide, I got to thinking about some of my biggest mistakes with respect to developing the Big 3 (squat, bench press, and deadlift). Here are the top five mistakes I made in my powerlifting career:

1. Going to powerlifting equipment too soon (or at all).

Let me preface this point by saying that I have a tremendous amount of respect for all powerlifters, including those who lift in powerlifting equipment like bench shirts and squat/deadlift suits. Honestly, they just weren't for me.

I first got into a bench shirt when I was 160 pounds, and my best raw bench press was about 240-250 pounds. I was deadlifting in the high 400s, and squatting in the mid 300s. In hindsight, it was much too soon; I simply needed to develop more raw strength. My squat and bench press went up thanks to the suit and shirt, respectively, but just about everything I unracked felt insanely heavy. I just don't think I had enough training experience under my belt without any supportive equipment to feel truly stable under big weights. It's funny, though; my heaviest deadlifts never felt like this, as it was the "rawest" of any of the big 3 lifts for me.

There's more, though. Suits and shirts were just an annoying distraction for me. I absolutely hated the time and nuisance of having to put them on in the middle of a lift; training sessions easily dragged on to be three hours, when efficiency was something I'd always loved about my training. Perhaps more significantly, getting proficient with equipment took a lot of time and practice, and the more I was in it, the less athletic I felt. I spent too much time box squatting and not enough free squatting, and felt like I never developed good bottom-end bench press strength because the shirt did so much of the work for me.

At the end of my equipped powerlifting career, I had squatted 540, bench pressed 402, deadlifted 650, and totaled 1532 in the 165-pound weight class. Good numbers - enough to put me in the Powerlifting USA Top 100 for a few years in a row - but not quite "Elite." I tentatively "retired" from competitive powerlifting in December of 2007 when Cressey Sports Performance grew rapidly, but kept training - this time to be athletic and have fun.

For the heck of it, in the fall of 2012, I decided to stage a "raw" mock meet one morning at the facility. At a body weight of 180, I squatted 455, bench pressed 350, and deadlifted 630 for a 1435 total. In other words, I totaled "Elite" by 39 pounds...and did the entire thing in 90 minutes.

Looking back, I think I could have been a much more accomplished competitive lifter - and saved money and enjoyed the process a lot more along the way - if I'd just stuck with raw lifting. Again, I don't fault others for using bench shirts and squat/deadlift suits, but they just weren't for me. I would just say that if you do decide to go the equipped route, you should be prepared to spend a lot more time in your equipment than I did, as my dislike of it (and lack of time spent in it) was the reason that I never really got proficient enough to thrive with it in meets.

2. Not understanding that fatigue masks fitness.

Kelly Baggett was the first person I saw post the quote, "Fatigue masks fitness." I thought I understand what it meant, but it wasn't until my first powerlifting meet that I experienced what it meant.

Thanks to a powerlifting buddy's urging, I went out of my way to take the biggest deload in my training career prior to my first meet. The end result? I pulled 510 on my last deadlift attempt - after never having pulled more than 480 in the gym.

You're probably stronger than you realize you are. You've just never given your body enough of a rest to actually demonstrate that strength.

3. Not getting around strong people sooner.

I've been fortunate to lift as part of some great training crews, from the varsity weight room at UCONN during my grad degree, to Southside Gym in Connecticut for a year, to Cressey Sports Performance for the past seven years.

When I compare these training environments to the ones I had in my early days - or even what I experience when I have to get a lift in on the road at a commercial gym - I can't help but laugh. Training around the right people in the right atmosphere makes a huge difference.

To that end, beyond just finding the right program, I always encourage up-and-coming lifters to seek out strong people for training partners, even if it means traveling a bit further to a different gym. Success happens at the edge of your comfort zone, and sometimes that means a longer commute and being the weakest guy in a room.

4. Spending too much time in the "middle zone" of cardio.

A lot of powerlifters will tell you that "cardio sucks." I happen to think it's a bit more complex than that.

Doing some quality work at a very low intensity (for me, this is below 70% of max heart rate) a few times a week can offer some very favorable aerobic adaptations that optimize recovery. Sorry, but it's not going to interfere with your gains if you walk on the treadmill a few times a week.

Additionally, I think working in some sprint work with near-full recovery can be really advantageous for folks who are trying to get stronger, as it trains the absolute speed end of the continuum.

As I look back on the periods in my training career when I've made the best progress, they've always included regular low-intensity aerobic work - as well as the occasion (1x/week) sprint session. When did cardio do absolutely nothing except set me back? When I spent a lot of time in the middle zone of 70-90% of max heart rate; it's no man's land! The take-home lesson is that if you want to be strong and powerful, make your low-intensity work "lower" and your high-intensity work "higher."

As an aside, this is where I think most baseball conditioning programs fail miserably; running poles falls right in this middle zone.

5. Thinking speed work had to be "all or nothing."

"Speed work" is one of the more hotly debated topics in the powerlifting world. I, personally, have always really thrived when I included it in my program. If you want to understand what it is and the "why" behind it, you can check out this article I wrote: 5 Reasons to Use Speed Deadlifts in Your Strength Training Programs.

A lot of people say that it's a waste of time for lifters who don't have an "advanced" level of strength, and that beginners would be better off getting in more rep work. As a beginner, I listened to this advice, and did lots of sets of 5-8 and never really focused on bar speed with lower reps. The end result? I was slower than death out of the hole on squats, off the chest on bench presses, and off the floor with deadlifts. And, it doesn't take much strength training knowledge to know that if you don't lift a weight fast, your chances of completing that lift aren't particularly good.

To the folks who "poo-poo" speed work, I'd just ask this: do you really think focusing on accelerating the bar is a bad thing?

Here's a wild idea, using bench presses as an example. If a lifter has a heavier bench press day and a more volume/repetition oriented day each week, what would happen if he did an extra 3-4 sets of three reps at 45-70% of 1-rep max load during his warm-up? Would that be a complete waste of time? Absolutely not! In fact, the casual observer would never even notice that it was happening.

The point is that speed work is easy to incorporate and really not that draining. You can still do it and get a ton of other quality work in, so there is really no reason to omit it. Having great bar speed will never hurt your cause, but not training it certainly can.

Looking to avoid these mistakes and many more - all while taking the guesswork out of your squat, bench press, and deadlift training? Check out The Specialization Success Guide. This comprehensive product to bring up the "Big 3" has been a huge hit; you can learn more HERE.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|

| Read more |

|

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|