A while back, I wrote up an article, 10 Important Notes on Assessments, that was one of my most popular posts of the year - and I'm ready for a sequel! Here are a few thoughts that came to mind.

1. Just like training, assessments are getting more specialized.

As the sports performance and even personal training worlds get more specialized, the assessments we need to utilize with our clients must be correctly matched up to the people in front of us. As examples, rotator cuff strength tests are huge for a baseball pitcher, but relatively unimportant for a soccer player. We’d “weight” a single-leg squat test result as less significant for a kayaker than we would for a basketball player. The goals of the client and the functional demands of their sport guide the assessments – both in terms of which ones we perform and how we value the results.

However, the challenge is that you can’t test everything, so it’s important to prioritize. If we used every assessment under the sun, the evaluation would last all day – and we’d spend an entire session pointing out everything that’s wrong with someone. I’d much rather use this time to build rapport.

A VO2max test isn’t high on my list of priorities for baseball players even if it might shed some light on their aerobic base. I can probably get the information I need just as easily – and much more affordably – by taking a quick resting heart rate measurement.

2. Every good test that has an unfavorable outcome immediately sets you up for an even more telling retest.

Assessments give you a glimpse into what could potentially be wrong or right about how someone moves. The more important question is: what interventions make a difference? Their squat pattern improves when you give them an anterior counterbalance? Their hip internal rotation improves when you add some core recruitment? Their shoulder pain goes away when the massage therapist works on their scalenes?

One tenet of the Selective Functional Movement Screen (SFMA) system is to always start with dysfunctional, non-painful patterns. What interventions clean up aberrant movement in non-painful areas to give us "easy" adaptations? This not only expands our movement repertoire, but also facilitates buy-in from the athlete/client.

3. Never go to movement screens without first performing a thorough health history and client “interview.”

I think we can all agree that a pre-participation evaluation can dramatically reduce the likelihood in training. And, I'd argue that the single most important part of this evaluation is the health history and conversation you have with them before they even start the movement screen portion of it.

As an example, imagine you have a hypermobile female client with a history of serious anterior shoulder instability that hasn't been surgically treated. If you do thorough paperwork and a detailed conversation with her, you'll quickly ascertain that you have to be careful with anything that involves shoulder external rotation. If you don't do that preliminary work, though, you might very well pop her shoulder out of the socket doing a basic external rotation range-of-motion test.

Summarily: paperwork first, conversation second, movement third!

4. Have assessment regressions for people who can’t perform certain tests due to pain or poor movement competencies.

I like to use a Titliest Performance Institute screen – lumbar locked rotation – to assess thoracic rotation. It requires an individual to get into a lot of knee flexion, though. So, if you have someone who is extremely short in their quads – or has had a knee replacement and permanently lost that motion, then it’s not a solid test.

You’re better off going to a seated thoracic rotation screen with these folks.

As a good rule of thumb, you’ll need more alternatives to general screens (involving more joints and motor control challenges) than you will for specific assessments (involving fewer). So, as you look through your assessment approach, start to consider how you’ll regress things when things don't go as planned.

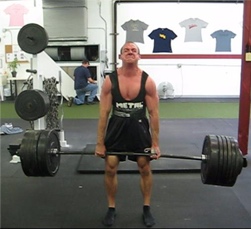

5. Don’t overlook evaluating training technique as a means of assessing.

During almost every evaluation of someone who has struggled with pain or performance (which is really everyone), I look at technique exercises they commonly perform. For our pitchers, this might be arm care exercises, or a video of a bullpen. For powerlifters, it might be technique on the squat, bench press, or deadlift. As much as our assessment protocols can be thorough, they’ll never fully offer the specificity that comes from watching people actually train.

6. Don’t use tests to embarrass people.

As an extension of the previous point, if you know someone is going to fail miserably on a screen, don’t test it. If you have a 350-pound woman who wants to lose 200 pounds, she’s not going to do well on a push-up test. You can assume that her upper body strength and core stability aren’t sufficient to handle her body weight.

I keep coming back to it:

7. Watch for straining.

This is something I’ve watched for a lot more in recent years after spending time around my business partner, Shane Rye, who’s one of the best manual therapists I have ever seen. He’s a master of watching people move and picking up on where they tend to store their tone. Maybe it’s jaw clenching when you test rotator cuff strength, or making an aggressive fist when you check their active straight leg raise. Watching for changes in accessory tone can give you a glimpse into where you might get the best benefit with your manual therapy work – and how you might coach them differently while they’re training.

8. The best outcome of an assessment might actually be a referral for a more thorough assessment.

At least once a year, I have an assessment come in - but without doing any training, I refer them on for further evaluation. Usually, it's because something very "clinical" in nature presents, and I feel that they need to see a medical professional before we start working with them. It doesn't happen often, but I'm never shy about "punting" when I feel that someone else is better equipped than I am to help the person in front of me.

9. Don’t take their word for it on body weight.

I once had a 6-8 pitcher tell me that he weighed 235 pounds. The next day, he walked in and remarked, “Coach, I actually weighed in this morning. I was 253 pounds.” Now, 18 pounds isn’t as huge a percentage of total body mass on a 6-8, 253 guy as it is on a 14-year-old, 110 pound female teenager, but it’s still tell us a lot that he could actually swing 18 pounds without even feeling it. That’s a sign of an athlete with poor body awareness and a lack of nutritional control (they definitely weren’t a good 18 pounds). You're better off measuring than just asking.

A side note: this applies to male athletes only; I never weigh female athletes for obvious reasons.

10. Take meticulous notes.

I often find myself looking back on notes we have on long-term clients to see how their movement (and prescribed training) has evolved over the years. It wouldn't be possible if I wasn't very detailed in my note-taking - and this is something I'm always striving to improve upon, as we want to create sustainable systems in our business.

Employees move on, so a client's programming responsibilities may be shifted to other staff members. Sports medicine professionals may want to work from some of our notes. Teams and agents might want information on what we discovered with a player and how we plan to manage them. The more you document, the more prepared you'll be in these situations when collaboration is necessary.

Most importantly, though, whenever I write a new program for a client, I have their evaluation form and their previous program open on my computer. I want to see what I initially noticed and put it alongside the up-to-date programming to verify where we are in our progressions. It's this kind of documentation that allows me to program for dozens of athletes who are not only in our facility, but across the country and overseas.

Wrap-up

I've been assessing athletes for close to 15 years, and I find that our evaluations evolve every single year. If you're looking to stay on top of some of the latest developments on this front, I'd strongly encourage you check out our Functional Stability Training series.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter and receive a four-part video series on how to deadlift!

|