|

I've gotten several emails over the past week from folks who read the following article in the New York Times:

Stretching: The Truth

You know what the questions were? I'll tell you (paraphrased):

"Didn't you already talk about this in your Magnificent Mobility DVD?"

Yes, as a matter of fact; we did. And, the MM DVD was filmed in November of 2005.

You know what else? With just a cursory glance at our references from peer-reviewed journals for MM, I found two separate studies supporting these facts from - believe it or not - 1999.

Sorry, folks; the New York Times is far from revolutionary. This news is at least nine years old - and even older when you consider that there were guys in the trenches experimenting with dynamic flexibility for decades before the research even came to fruition.

This same "delay" kicked in about a year ago when everyone went crazy when we finally "discovered" in the mainstream media that lactic acid was not the cause of muscular fatigue. I actually first heard this in 2004 back in a Muscle Physiology class in graduate school at the University of Connecticut. This review by Robergs et al. at the University of New Mexico was what opened a lot of people's eyes.

This same "delay" kicked in about a year ago when everyone went crazy when we finally "discovered" in the mainstream media that lactic acid was not the cause of muscular fatigue. I actually first heard this in 2004 back in a Muscle Physiology class in graduate school at the University of Connecticut. This review by Robergs et al. at the University of New Mexico was what opened a lot of people's eyes. |

| Read more |

|

1. This has been quite possibly the busiest week of my career, and it won't be slowing down over the next two weeks, as I'm heading to Baltimore, Miami, and Atlanta in three separate trips. We will persevere with this blog, though...

Factor in that I was up until the wee hours of the morning last night watching the Sox pull off without a doubt the greatest comeback I've ever seen in a single game in any sport, and sleep deprivation is becoming part of the equation...

2. Quite possibly the most awesome forum post directed to me ever:

I own your Magnificent Mobility DVD and Maximum Strength book. The content is revolutionary, at least to somebody like me, who's never had professional strength and conditioning training.

Each is presented in an easy to understand format, but dive into science enough to capture the technical audience as well. The pictures and demonstrations are very valuable to illustrate the key points in each exercise.

There is one thing missing, though. The guy modeling all the exercises could look a little tougher. He absolutely needs a fu manchu moustache.

That would perfect your programs. I know it's too late to revise the current products, but please promise me that in future products the model will be sporting some Goose Gossage handlebars.

2. Quite possibly the most awesome forum post directed to me ever:

I own your Magnificent Mobility DVD and Maximum Strength book. The content is revolutionary, at least to somebody like me, who's never had professional strength and conditioning training.

Each is presented in an easy to understand format, but dive into science enough to capture the technical audience as well. The pictures and demonstrations are very valuable to illustrate the key points in each exercise.

There is one thing missing, though. The guy modeling all the exercises could look a little tougher. He absolutely needs a fu manchu moustache.

That would perfect your programs. I know it's too late to revise the current products, but please promise me that in future products the model will be sporting some Goose Gossage handlebars.

He makes a good point. Once you're magnificently mobile and maximally strong, you might as well be dead-sexy...

3. A lot of people mistake a big butt for anterior pelvic tilt. When the butt sticks out (known as a "badonkadonk," if you ask Tony Gentilcore), it can give the illusion of anterior pelvic tilt when, in reality, these folks might be fine posture-wise. So, you have to look closely (but not too closely; they might slap you, pervert).

So, to recap: Big Butt = Good. Anterior Pelvic Tilt = Bad.

4. The Anti-Cressey Performance. Soooooo Lame.

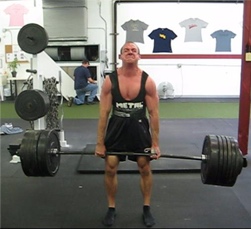

5. In the upset of the week, in the "Stupidest Thing Ever Invented Bowl," the Smith Machine Deadlift narrowly defeated the Meat-Cleaver Colonoscopy.

6. In the past week, I've had three different people tell me that Cressey Performance needs to get with the program and offer mentorships with me. To be honest, it's something I've been pondering for the past month or so, and we're really thinking about putting something special together. If we did it, it would be tight-knit: no more than six attendees at a time. If you'd be interested in something like this, drop us an email at cresseyperformance@gmail.com and let us know.

7. Interesting little fact for the week: 85% of ACL reconstructive surgeries are performed by surgeons who do fewer than ten ACL surgeries per year. So, ask around before you let someone stick an arthroscope in your knee! Or, better yet, pick up a copy of Bulletproof Knees and avoid the ACL injury in the first place!

8. Speaking of healthy knees, check out last week's newsletter. I had some great knee-related content courtesy of Mike Robertson.

Lots to do. See you next week.

He makes a good point. Once you're magnificently mobile and maximally strong, you might as well be dead-sexy...

3. A lot of people mistake a big butt for anterior pelvic tilt. When the butt sticks out (known as a "badonkadonk," if you ask Tony Gentilcore), it can give the illusion of anterior pelvic tilt when, in reality, these folks might be fine posture-wise. So, you have to look closely (but not too closely; they might slap you, pervert).

So, to recap: Big Butt = Good. Anterior Pelvic Tilt = Bad.

4. The Anti-Cressey Performance. Soooooo Lame.

5. In the upset of the week, in the "Stupidest Thing Ever Invented Bowl," the Smith Machine Deadlift narrowly defeated the Meat-Cleaver Colonoscopy.

6. In the past week, I've had three different people tell me that Cressey Performance needs to get with the program and offer mentorships with me. To be honest, it's something I've been pondering for the past month or so, and we're really thinking about putting something special together. If we did it, it would be tight-knit: no more than six attendees at a time. If you'd be interested in something like this, drop us an email at cresseyperformance@gmail.com and let us know.

7. Interesting little fact for the week: 85% of ACL reconstructive surgeries are performed by surgeons who do fewer than ten ACL surgeries per year. So, ask around before you let someone stick an arthroscope in your knee! Or, better yet, pick up a copy of Bulletproof Knees and avoid the ACL injury in the first place!

8. Speaking of healthy knees, check out last week's newsletter. I had some great knee-related content courtesy of Mike Robertson.

Lots to do. See you next week. |

| Read more |

|

By Eric Cressey

Originally featured at charlespoliquin.net

Even the best athletes are limited by their most significant weaknesses. For some athletes, weaknesses may be mental barriers along the lines of fear of playing in front of large crowds, or getting too fired up before a big contest. Others may find that the chink in their armor rests with some sport-specific technique, such as shooting free throws. While these two realms can best be handled by the athletes' head coaches and are therefore largely outside of the control of a strength and conditioning coach, there are several categories of weak links over which a strength and conditioning specialist can have profound impacts. These impacts can favorably influence athletes' performance while reducing the risk of injury. With that in mind, what follows is far from an exhaustive list of the weaknesses that strength and conditioning professionals may observe, especially given the wide variety of sports one encounters and the fact that the list does not delve into neural, hormonal, or metabolic factors. Nonetheless, in my experience, these are the ten most common biomechanical weak links in athletes:

1. Poor Frontal Plane Stability at the Hips: Frontal plane stability in the lower body is dependent on the interaction of several muscle groups, most notably the three gluteals, tensor fascia latae (TFL), adductors, and quadratus lumborum (QL). This weakness is particularly evident when an athlete performs a single-leg excursion and the knee falls excessively inward or (less commonly) outward. Generally speaking, weakness of the hip abductors – most notably the gluteus medius and minimus – is the primary culprit when it comes to the knee falling medially, as the adductors, QL, and TFL tend to be overactive. However, lateral deviation of the femur and knee is quite common in skating athletes, as they tend to be very abductor dominant and more susceptible to adductor strains as a result. In both cases, closed-chain exercises to stress the hip abductors or adductors are warranted; in other words, keep your athletes off those sissy obstetrician machines, as they lead to a host of dysfunction that's far worse that the weakness the athlete already demonstrates! For the abductors, I prefer mini-band sidesteps and body weight box squats with the mini-band wrapped around the knees. For the adductors, you'll have a hard time topping lunges to different angles, sumo deadlifts, wide-stance pull-throughs, and Bulgarian squats.

2. Weak Posterior Chain: Big, fluffy bodybuilder quads might be all well and good if you're into getting all oiled up and "competing" in posing trunks, but the fact of the matter is that the quadriceps take a back seat to the posterior chain (hip and lumbar extensors) when it comes to athletic performance. Compared to the quads, the glutes and hamstrings are more powerful muscles with a higher proportion of fast-twitch fibers. Nonetheless, I'm constantly amazed at how many coaches and athletes fail to tap into this strength and power potential; they seem perfectly content with just banging away with quad-dominant squats, all the while reinforcing muscular imbalances at both the knee and hip joints. The muscles of the posterior chain are not only capable of significantly improving an athlete's performance, but also of decelerating knee and hip flexion. You mustn't look any further than a coaches' athletes' history of hamstring and hip flexor strains, non-contact knee injuries, and chronic lower back pain to recognize that he probably doesn't appreciate the value of posterior chain training. Or, he may appreciate it, but have no idea how to integrate it optimally. The best remedies for this problem are deadlift variations, Olympic lifts, good mornings, glute-ham raises, reverse hypers, back extensions, and hip-dominant lunges and step-ups. Some quad work is still important, as these muscles aren't completely "all show and no go," but considering most athletes are quad-dominant in the first place, you can usually devote at least 75% of your lower body training to the aforementioned exercises (including Olympic lifts and single-leg work, which have appreciable overlap).

Regarding the optimal integration of posterior chain work, I'm referring to the fact that many athletes have altered firing patterns within the posterior chain due to lower crossed syndrome. In this scenario, the hip flexors are overactive and therefore reciprocally inhibit the gluteus maximus. Without contribution of the gluteus maximus to hip extension, the hamstrings and lumbar erector spinae muscles must work overtime (synergistic dominance). There is marked anterior tilt of the pelvis and an accentuated lordotic curve at the lumbar spine. Moreover, the rectus abdominus is inhibited by the overactive erector spinae. With the gluteus maximus and rectus abdominus both at a mechanical disadvantage, one cannot optimally posteriorly tilt the pelvis (important to the completion of hip extension), so there is lumbar extension to compensate for a lack of complete hip extension. You can see this quite commonly in those who hit sticking points in their deadlifts at lockout and simply lean back to lock out the weight instead of pushing the hips forward simultaneously. Rather than firing in the order hams-glutes- contralateral erectors-ipsilateral erectors, athletes will simply jump right over the glutes in cases of lower crossed syndrome. Corrective strategies should focus on glute activation, rectus abdominus strengthening, and flexibility work for the hip flexors, hamstrings, and lumbar erector spinae.

3. Lack of Overall Core Development: If you think I'm referring to how many sit-ups an athlete can do, you should give up on the field of performance enhancement and take up Candyland. The "core" essentially consists of the interaction among all the muscles between your shoulders and your knees; if one muscle isn't doing its job, force cannot be efficiently transferred from the lower to the upper body (and vice versa). In addition to "indirectly" hammering on the core musculature with the traditional compound, multi-joint lifts, it's ideal to also include specific weighted movements for trunk rotation (e.g. Russian twists, cable woodchops, sledgehammer work), flexion (e.g. pulldown abs, Janda sit-ups, ab wheel/bar rollouts), lateral flexion (e.g. barbell and dumbbell side bends, overhead dumbbell side bends), stabilization (e.g. weighted prone and side bridges, heavy barbell walkouts), and hip flexion (e.g. hanging leg raises, dragon flags). Most athletes have deficiencies in strength and/or flexibility in one or more of these specific realms of core development; these deficiencies lead to compensation further up or down the kinetic chain, inefficient movement, and potentially injury.

4. Unilateral Discrepancies: These discrepancies are highly prevalent in sports where athletes are repetitively utilizing musculature on one side but not on the contralateral side; obvious examples include throwing and kicking sports, but you might even be surprised to find these issues in seemingly "symmetrical" sports such as swimming (breathing on one side only) and powerlifting (not varying the pronated/supinated positions when using an alternate grip on deadlifts). Obviously, excessive reliance on a single movement without any attention to the counter-movement is a significant predisposition to strength discrepancies and, in turn, injuries. While it's not a great idea from an efficiency or motor learning standpoint to attempt to exactly oppose the movement in question (e.g. having a pitcher throw with his non-dominant arm), coaches can make specific programming adjustments based on their knowledge of sport-specific biomechanics. For instance, in the aforementioned baseball pitcher example, one would be wise to implement extra work for the non-throwing arm as well as additional volume on single-leg exercises where the regular plant-leg is the limb doing the excursion (i.e. right-handed pitchers who normally land on their left foot would be lunging onto their right foot). Obviously, these modifications are just the tip of the iceberg, but simply watching the motion and "thinking in reverse" with your programming can do wonders for athletes with unilateral discrepancies.

5. Weak Grip: – Grip strength encompasses pinch, crushing, and supportive grip and, to some extent, wrist strength; each sport will have its own unique gripping demands. It's important to assess these needs before randomly prescribing grip-specific exercises, as there's very little overlap among the three types of grip. For instance, as a powerlifter, I have significantly developed my crushing and supportive grip not only for deadlifts, but also for some favorable effects on my squat and bench press. Conversely, I rarely train my pinch grip, as it's not all that important to the demands on my sport. A strong grip is the key to transferring power from the lower body, core, torso, and limbs to implements such as rackets and hockey sticks, as well as grappling maneuvers and holds in mixed martial arts. The beauty of grip training is that it allows you to improve performance while having a lot of fun; training the grip lends itself nicely to non-traditional, improvisational exercises. Score some raw materials from a Home Depot, construction site, junkyard, or quarry, and you've got dozens of exercises with hundreds of variations to improve the three realms of grip strength. Three outstanding resources for grip training information are Mastery of Hand Strength by John Brookfield, Grip Training for Strength and Power Sports by accomplished Strongman John Sullivan, and www.DieselCrew.com.

6. Weak Vastus Medialis Oblique (VMO): The VMO is important not only in contributing to knee extension (specifically, terminal knee extension), but also enhancing stability via its role in preventing excessive lateral tracking of the patella. The vast majority of patellar tracking problems are related to tight iliotibial bands and lateral retinaculum and a weak VMO. While considerable research has been devoted to finding a good "isolation" exercise for the VMO (at the expense of the overactive vastus lateralis), there has been little success on this front. However, anecdotally, many performance enhancement coaches have found that performing squats through a full range of motion will enhance knee stability, potentially through contributions from the VMO related to the position of greater knee flexion and increased involvement of the adductor magnus, a hip extensor (you can read a more detailed analysis from me here. Increased activation of the posterior chain may also be a contributing factor to this reduction in knee pain, as stronger hip musculature can take some of the load off of the knee stabilizers. As such, I make a point of including a significant amount of full range of motion squats and single-leg closed chain exercises (e.g. lunges, step-ups) year-round, and prioritize these movements even more in the early off-season for athletes (e.g. runners, hockey players) who do not get a large amount of knee-flexion in the closed-chain position in their regular sport participation.

7 & 8. Weak Rotator Cuff and/or Scapular Stabilizers: I group these two together simply because they are intimately related in terms of shoulder health and performance.

Although each of the four muscles of the rotator cuff contributes to humeral motion, their primary function is stabilization of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa of the scapula during this humeral motion. Ligaments provide the static restraints to excessive movement, while the rotator cuff provides the dynamic restraint. It's important to note, however, that even if your rotator cuff is completely healthy and functioning optimally, you may experience scapular dyskinesis, shoulder, upper back, and neck problems because of inadequate strength and poor tonus of the muscles that stabilize the scapula. After all, how can the rotator cuff be effective at stabilizing the humeral head when its foundation (the scapula) isn't stable itself? Therefore, if you're looking to eliminate weak links at the shoulder girdle, your best bet is to perform both rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer specific work. In my experience, the ideal means of ensuring long-term rotator cuff health is to incorporate two external rotation movements per week to strengthen the infraspinatus and teres minor (and the posterior deltoid, another external rotator that isn't a part of the rotator cuff). On one movement, the humerus should be abducted (e.g. elbow supported DB external rotations, Cuban presses) and on the other, the humerus should be adducted (e.g. low pulley external rotations, side-lying external rotations). Granted, these movements are quite basic, but they'll do the job if injury prevention is all you seek. Then again, I like to integrate the movements into more complex schemes (some of which are based on PNF patterns) to keep things interesting and get a little more sport-specific by involving more of the kinetic chain (i.e. leg, hip, and trunk movement). On this front, reverse cable crossovers (single-arm, usually) and dumbbell swings are good choices. Lastly, for some individuals, direct internal rotation training for the subscapularis is warranted, as it's a commonly injured muscle in bench press fanatics. Over time, the subscapularis will often become dormant – and therefore less effective as a stabilizer of the humeral head - due to all the abuse it takes.

For the scapular stabilizers, most individuals fall into the classic anteriorly tilted, winged scapulae posture (hunchback); this is commonly seen with the rounded shoulders that result from having tight internal rotators and weak external rotators. To correct the hunchback look, you need to do extra work for the scapular retractors and depressors; good choices include horizontal pulling variations (especially seated rows) and prone middle and lower trap raises. The serratus anterior is also a very important muscle in facilitating scapular posterior tilt, a must for healthy overhead humeral activity. Supine and standing single-arm dumbbell protractions are good bets for dynamically training this small yet important muscle; scap pushups, scap dips, and scap pullups in which the athlete is instructed to keep the scapulae tight to the rib cage are effective isometric challenges to the serratus anterior.

Concurrently, athletes with the classic postural problems should focus on loosening up the levator scapulae, upper traps, pecs, lats, and anterior delts. One must also consider if these postural distortions are compensatory for kinetic chain dysfunction at the lumbar spine, pelvis, or lower extremities. My colleague Mike Robertson and I have written extensively on this topic here. Keep in mind that all of this advice won't make a bit of difference if you have terrible posture throughout the day, so pay as much attention to what you do outside the weight room as you do to what goes on inside it.

9. Weak Dorsiflexors: It's extremely common for athletes to perform all their movements with externally rotated feet. This positioning is a means of compensating for a lack of dorsiflexion range of motion – usually due to tight plantarflexors - during closed-chain knee flexion movements. In addition to flexibility initiatives for the calves, one should incorporate specific work for the dorsiflexors; this work may include seated dumbbell dorsiflexions, DARD work, and single-leg standing barbell dorsiflexions. These exercises will improve dynamic postural stability at the ankle joint and reduce the risk of overuse conditions such as shin splints and plantar fasciitis.

10. Weak Neck Musculature: The neck is especially important in contact sports such as football and rugby, where neck strength in all planes is highly valuable in preventing injuries that may result from collisions and violent jerking of the neck. Neck harnesses, manual resistance, and even four-way neck machines are all good bets along these lines, as training the neck can be somewhat awkward. From a postural standpoint, specific work for the neck flexors is an effective means of correcting forward head posture when paired with stretches for the levator scapulae and upper traps as well as specific interventions to reduce postural abnormalities at the scapulae, humeri, and thoracic spine. In this regard, unweighted chin tucks for high reps throughout the day are all that one really needs. This is a small training price to pay when you consider that forward head posture has been linked with chronic headaches.

Closing Thoughts

A good coach recognizes that although the goals of improving performance and reducing the risk of injury are always the same, there are always different means to these ends. In my experience, one or more of the aforementioned ten biomechanical weak links is present in almost all athletes you encounter. Identifying biomechanical weak links is an important prerequisite to choosing one's means to these ends. This information warrants consideration alongside neural, hormonal, and metabolic factors as one designs a comprehensive program that is suited to each athlete's unique needs. |

| Read more |

|

Last week, I was fortunate enough to get a free copy of Mike Robertson and Bill Hartman’s 2008 Indianapolis Performance Enhancement Seminar DVD Set. To be honest, the word “fortunate” doesn’t even begin to do the product justice; it was the best industry product I’ve watched all year.

The DVD set is broken up into six separate presentations:

1. Introduction and 21st Century Core Training

2. Creating a More Effective Assessment

3. Optimizing Upper Extremity Biomechanics

4. Building Bulletproof Knees

5. Selecting the Optimal Method for Effective Flexibility Training

6. Program Design and Conclusion

To be honest, I’ve already seen Mike Robertson deliver the presentations on DVDs 1 and 4 a few times during seminars at which we’ve both presented, so more of my focus in this review will be on Bill’s presentations because they were more “new” to me. That said, I can tell you that each time I’ve seen Mike deliver there presentations, he’s really impressed the audience and put them in a position to view training from a new (and better) paradigm, debunking old myths along the way. A lot of the principles in his core training presentation mirror what we do with our clients – and particularly with those involved in rotational sports.

Bill’s presentation on assessments is excellent. I think I liked it the most because it really demonstrated Bill’s versatility in that he knows how to assess both on the clinical (physical therapy) and asymptomatic (ordinary client/athlete) sides of the things. A few quick notes from Bill’s presentation that I really liked:

a. Roughly 40% of athletes have a leg length discrepancy – but that’s not to say that 40% of athletes are injured or even symptomatic. As such, we need to understand that some asymmetry is normal in many cases – and determining what is an acceptable amount of asymmetry is an important task. As an example, in my daily work, a throwing shoulder internal rotation deficit (relative to the non-throwing shoulder) of 15 degrees or less is acceptable – but if a guy goes over 15°, he really needs to buckle down on his flexibility work and cut back on throwing temporarily. If he is 17-18° or more, he shouldn’t be throwing – period.

b. It’s important to consider not only a client/patient/athlete looks like on a “regular” test, but also under conditions of fatigue. There’s a reason athletes get hurt more later in games: fatigue changes movement efficiency and safety! This is why many tests should include several reps – and we should always be looking to evaluate players “on the fly” under conditions of fatigue.

c. Bill made a great point on “functional training” during this presentation as well – and outlined the importance difference between kinetics (incorporates forces) and kinematics (movement independent of forces). Most functional training zealots only look at kinematics, and in the process, ignore the amount of forces in a dynamic activity. For example, being able to execute a body weight lateral lunge with good technique doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be “equipped” to handle change-of-direction challenges at game speed. In reality, this force consideration is one reason why there are times that bilateral exercise is actually more function than unilateral movements!

d. Bill also outlined a multi-faceted scoring system he uses to evaluate athletes in the context of their sports. It’s definitely a useful system for those who want a quantifiable scheme through which to score athletes on overall strength, speed, and flexibility qualities to determine areas that warrant prioritization.

DVD #3 is an excellent look at preventing and correcting shoulder problems – and in terms of quality, this presentation with Mike is right on par with their excellent Inside-Out DVD. Mike goes into depth on what causes most shoulder problems and how we can work backward from pathology to see what movement deficiency – particularly scapular downward rotation syndrome – caused the problem. There is a great focus on lower trapezius and serratus anterior strengthening exercises and appropriate flexibility drills for the pec minor, levator scapulae, and thoracic spine – as well as a focus on the effects of hip immobility and rectus abdominus length on upper body function.

To be honest, I think that DVD #4 alone is worth far more than the price of the entire set. It actually came at an ideal time for me, as I’m preparing our off-season training templates for our pro baseball guys – and flexibility training is a huge component of this. Whenever I see something and it really gets me thinking about what I’m doing, I know it’s great. Bill’s short vs. stiff discussion really did that for me.

Bill does far more justice to the discussion than I can, but the basic gist of the topic is that the word “tight” doesn’t tell us much at all. A short muscle actually has lost sarcomeres because it’s been in a shortened state for an extended period of time; this would be consistent with someone who had been immobilized post-surgery or a guy who has just spent way too long at a computer. These situations mandate some longer duration static stretching to really get after the plastic portion of connective tissue – and this can be uncomfortable, but highly effective.

Conversely, a stiff muscle is one that can be relatively easily lengthened acutely as long as you stabilize the less stiff segment. An example would be to stabilize the scapula when stretching someone into humeral internal or external rotation. If the scapular stabilizers are weak (i.e., not stiff), manually fixing the scapula allows us to effectively stretch the muscles acting at the humeral head. If we don’t stabilize the less-stiff joint, folks will just substitute range of motion there instead of where we actually want to create it. In situations like this, in addition to good soft tissue work, Bill recommends 30s static stretches for up to four rounds (this is not to be performed pre-exercise, though; that’s the ideal time for dynamic flexibility drills.

DVD #5 is where Mike is at his best: talking knees. This is a great presentation not only because of the quality of his information, but also because of his frame of reference; Mike has overcome some pretty significant knee issues, including a surgery to repair a torn meniscus. Mike details the role of ankle and hip restrictions in knee issues, covers the VMO isolation mindset, and outlines some of the research surrounding resistance training and rehabilitation of knee injuries in light of some of the myths that are abundant in the weight-training world.

DVD #6 brings all these ideas together with respect to program design.

I should also mention that each DVD also includes the audience Q&A, which is a nice bonus to the presentations themselves. The production quality is excellent, with “back-and-forths” between the slideshow and presenters themselves. Bill and Mike include several video demonstrations in their presentations to break up the talking and help out the visual learners in the crowd, too.

All in all, this is a fantastic DVD set that encompasses much more than I could ever review here. In fact, if it’s any indicator of how great I think it is, I’m actually going to have all our staff members watch it. If you train athletes or clients, definitely get it. Or, if you’re just someone who wants to know how to keep knees, shoulders, and lower backs healthy while optimizing flexibility, it’s worth every penny. You can find out more at the Indianapolis Performance Enhancement Seminar website.

New Blog Content

Maximum Strength: The Personal Trainer’s Perspective

Random Friday Thoughts: 7/25/08

Training around Knee Pain

Willing and Abele

All the Best,

EC

|

| Read more |

|

On Monday night, Josh Hamilton put on an amazing show with 28 homeruns in the first round of the MLB Homerun Derby. While he went on to lose to Justin Morneau in the finals of the contest, Hamilton did smash four 500+ ft. shots - and stole the hearts of a lot of New York fans. It's an incredible story; Hamilton has bounced back from eight trips to rehabilitation for drugs and alcohol to get to where he is today.

Geek that I am, though, I spent much of the time focusing on the incredible hip rotation and power these guys display on every swing. According to previous research, the rotational position of the lead leg changes a ton from foot off to ball contact. After hitting a maximal external rotation of 28° during the foot off “coiling” that takes place, those hips go through some violent internal rotation as the front leg gets stiff to serve as a “block” over which crazy rotational velocities are applied.

How crazy are we talking? How about 714°/s at the hips? This research on minor leaguers also showed that stride length averaged 85cm - or roughly 380% of hip width. So, you need some pretty crazy abduction and internal rotation range-of-motion (ROM) to stay healthy. And, of course, you need some awesome deceleration strength – and plenty of ROM in which to apply it – to finish like this.

Meanwhile, players are dealing with a maximum shoulder and arm segment rotational velocities of 937°/s and 1160°/s, respectively. All of this happens within a matter of 0.57 seconds. Yes, about a half a second.

These numbers in themselves are pretty astounding – and probably rivaled only by the crazy stuff that pitchers encounter on each throw. All these athletes face comparable demands, though, in the sense that these motions take a tremendous timing to sequence optimally. In particular, in both the hitting and pitching motions, the hip segment begins counterclockwise (forward) movement before the shoulder segment (which is still in the cocking/coiling phase). Check out this photo of Tim Hudson (more on this later):

Many of you have probably heard about a “new” injury in major league baseball – oblique strains – which have left a lot of people looking for answers. In fact, the USA Today published a great article on this exact topic earlier this season. Guys like Hudson, Chris Young, Manny Ramirez, Albert Pujols, Chipper Jones and Carlos Beltran (among others) have dealt with this painful injury in recent years. You know the best line in this entire article? With respect to Hudson:

“After the 2005 season, he stopped doing core work and hasn't had a problem. Could that be the solution?”

I happen to agree with the mindset that some core work actually contributes to the dysfunction – and the answer (to me, at least) rests with where the injury is occurring: “always on the opposite side of their throwing arm and often with the muscle detaching from the 11th rib.” If I’m a right-handed pitcher (or hitter) and my left hip is already going into counter-clockwise movement as my upper body is still cocking/coiling in clockwise motion – both with some crazy rotational velocities – it makes sense that the area that is stretched the most is going to be affected if I’m lacking in ROM at the hips or thoracic spine.

I touched on the need for hip rotation ROM, but the thoracic spine component ties right into the “core work” issue. Think about it this way: if I do thousands of crunches and/or sit-ups over the course of my career – and the attachment points of the rectus abdominus (“abs”) are on the rib cage and pelvis – won’t I just be pulling that rib cage down with chronic shortening of the rectus, thus reducing my thoracic spine ROM in the process?

Go take another look at the picture of Tim Hudson above. If he lacks thoracic spine ROM, he’s either going to jack his lower back into lumbar hyperextension and rotation as he tries to “lay back” during the late cocking phase, or he’s just going to strain an oblique. It’s going to be even worse if he has poor hip mobility and poor rotary stability – or the ability to resist rotation where you don’t want it.

Now, I’m going to take another bold statement – but first some quick background information:

1. Approximately 50-55% of pitching velocity comes from the lower extremity.

2. Upper extremity EMG activity during the baseball swing is nothing compared to what goes on in the lower body. In fact, Shaffer et al. commented, “The relatively low level of activity in the four scapulohumeral muscles tested indicated that emphasis should be placed on the trunk and hip muscles for a batter's strengthening program.”

So, the legs are really important; that 714°/s at the hips has to come from somewhere. And, more importantly, it’s my firm belief that it has to stay within a reasonable range of the shoulder and arm segment rotational velocities of 937°/s and 1160°/s (respectively). So, what happens when we give a professional baseball player a foo-foo training program that does little to build or even maintain lower-body strength and power? And, what happens when we have that player run miles at a time to “build up leg strength?” How many marathoners do you know who throw 95mph and need those kind of rotational velocities or ranges of motion? Apparently, bigger contracts equate to weaker, tighter legs…

Meanwhile, guys receive elaborate throwing programs to condition their arms – and they obviously never miss an upper-body day (also known as a “beach workout"). However, the lower-body is never brought up to snuff – and it lags off even more in-season when lifting frequency is lower and guys do all sorts of running to “flush their muscles.” The end result is that the difference between 714°/s (hips) and 937°/s and 1160°/s (shoulders and arms) gets bigger and bigger. Guys also lose lead-leg hip internal rotation over the course of the season if they aren’t diligent with their hip mobility work.

So, in my opinion, here’s what we need to do avoid these issues:

1. Optimize hip mobility – particularly with respect to hip internal rotation and extension. It is also extremely important to realize the effect that poor ankle mobility has on hip mobility; you need to have both, so don’t just stretch your hip muscles and then walk around in giant high-tops with big heel-lifts all day.

2. Improve thoracic spine range of motion into extension and rotation.

3. Get rid of the conventional “ab training/core work” and any yoga or stretching positions that involve lumbar rotation or hyperextension and instead focus exclusively on optimizing rotary stability and the ability to isometrically resist lumbar hyperextension.

4. Get guys strong in the lower body, not just the upper body.

5. Don’t overlook the importance of reactive work both in the lower and upper-body. I’ve read estimates that approximately 25-30% of velocity comes from elastic energy. So, sprint, jump, and throw the medicine balls.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Baseball Newsletter and Receive a 47-Minute Presentation on Individualizing the Management of Overhead Athletes!

|

| Read more |

|

| Fantasy Day at Fenway Park

I’ll be making my Fenway Park debut on Saturday. I know it’s hard to believe, but it won’t be for my catching abilities, base-stealing prowess, or 95-mph two-seam fastball. Rather, I’ll be speaking on a panel at the annual Fenway Park Fantasy Day to benefit The Jimmy Fund. And, if people don’t give a hoot about listening to me, they’ve got a skills zone with batting cages, a fast-pitch challenge, and accuracy challenge on top of loads of contests and tours. I’ll be sure to snap some photos for you.

This is an absolutely great cause, and while I know most of you won’t be in attendance, I’d highly encourage you to support the cause with a donation to the Jimmy Fund. What they are doing is something very special, and I’m honored to be a part of it.

Subscriber Only Q&A

Q: One quick question. As a trainer, I'm sure you've come across certain clients who have a problem with their thoracic spine (mild hump) and need to work on mobilizing this region. Other than foam rollers, are there any other techniques or methods that can be used? Maybe there's a book or video out there I could purchase that gives me a better understanding of how to implement some new methods?

A: Thanks for the email. It really depends on whether you're dealing with someone who just has an accentuated kyphotic curve or someone who actually has some sort of clinical pathology (e.g. osteoporosis, ankylosing spondylitis, Cushing’s Syndrome) that's causing the "hump." In the latter case, you obviously need to be very careful with exercise modalities and leave the “correction” to those qualified to deal with the pathologies in question.

In the former case, however, there’s quite a bit that you can do. You mentioned using a foam roller as a “prop” around which you can do thoracic extensions:

Thoracic Extensions on Foam Roller

While some people think that tractioning the thoracic spine in this position is a bad idea, I don’t really agree. We’ve used the movement with great success and absolutely zero negative feedback or outcomes.

That said, I’m a firm believer that the overwhelming majority of thoracic spine mobilizations you do should integrate extension with rotation. We don’t move straight-ahead very much in the real-world, so the rotational t-spine mobility is equally important. Mike Robertson and Bill Hartman do an awesome job of outlining several exercises along these lines in their Inside-Out DVD; I absolutely love it.

With most of these exercises, you’re using motion of the humerus to drive scapular movement and, in turn, thoracic spine movement.

The importance of t-spine rotation again rang true earlier this week when I had lunch with Neil Rampe, director of corrective exercise and manual therapy for the Arizona Diamondbacks. Neil is a very skilled and intuitive manual therapist, and he had studied extensively (and observed) the effect of respiration. He made some great points about how we can’t get too caught up in symmetry. Neil noted that we’ve got a heart in the upper left quadrant, and a liver in the lower right. The left lung has two lobes, and the right lung has three – and there’s some evidence to suggest that folks can usually fill their left lung easier than their right. The right diaphragm is bigger than the left –and it can use the liver for “leverage.” The end result is that the right rib winds up with a subtle internally rotated position, which in turns affects t-spine and scapular positioning. Needless to say, Neil is a smart dude – and once I got over how stupid I felt – I started scribbling notes. I’m going to be looking a lot more at breathing patterns as a result of this lunch.

Additionally, it’s very important to look at the effects of hypomobility and hypermobility elsewhere on thoracic spine posture. If you’re stuck in anterior pelvic tilt with a lordotic spine, your t-spine will have to compensate by rounding in order to keep you erect. And, if you’ve shortened your pecs and pulled the scapulae into anterior tilt and protraction, you’ll have a t-spine that’s been pulled into flexion. Or, if you’ve done thousands and thousands of crunches, chances are that you’ve shortened your rectus abdominus so much that your rib cage is depressed to the point of pulling you into a kyphotic position.

On the hypermobility front, poor rotary stability at the lumbar spine can lead to excessive movement at a region of the spine that really isn’t designed to move. It’s one reason why I like Jim Smith’s Combat Core product so much; he really emphasize rotary stability with a lot of his exercises. Lock up the lumbar spine a bit, and you’ll get more bang for your buck on the t-spine mobilizations.

As valuable as all the t-spine extension and rotation drills can be, they are – when it really comes down to it – just mobility drills. And, to me, mobility drills yield transient effects that must be sustained and complemented by appropriate strength and endurance of surrounding musculature. Above all else, strength of the appropriate scapular retractors (lower and middle trapezius) is important. You can be very strong in horizontal pulling – but have terrible posture and shoulder pain – if you don’t row correctly.

Not being cognizant of head and neck position can lead to a faulty neck pattern:

Cervical hyperextension (Chin Protrusion) Pattern

Here, little to no scapular retraction takes place. And, whatever work is done by the scapular retractors comes from the upper traps and rhomboids – not what we want to hit.

Then, every gym has this guy. He just uses his hip and lumbar extensors to exaggerate his lordotic posture and avoid using his scapular retractors at all costs.

Another more common, but subtle technical flaw is the humeral extension with scapular elevation. Basically, by leaning back a bit more, an individual can substitute humeral extension for much of the scapular retraction that takes place – so basically, the lats and upper traps are doing all the work. This can be particularly stressful on the anterior shoulder capsule in someone with a scapula that sits in anterior tilt because of restrictions on pec minor, coracobrachialis, or short head of the biceps. Here is what that issue looks like when someone is upright like they should be. A good seated row would like like this last one – but with the shoulder blades pulled back AND down. We go over a lot of common flaws like these in our Building the Efficient Athlete DVD series.

Finally, don’t overlook the role that soft tissue quality plays with all of this. Any muscle – pec minor, coracobrachialis, short head of the biceps – that anteriorly tilts the scapulae can lead to these posture issues. Likewise, levator scapulae, scalenes, subclavius, and some of the big muscles like pec major, lats, and teres major can play into the problem as well. I’ve always looked at soft tissue work as the gateway to corrective exercise; it opens things up so that you can get more out of your mobility/activation/resistance exercise.

Hopefully, this gives you some direction.

All the Best,

EC

Sign-up Today for our FREE Baseball Newsletter and Receive a Copy of the Exact Stretches

used by Cressey Performance Pitchers after they Throw!

|

| Read more |

|

| New Article

I had a new article published on Tuesday at T-Nation; be sure to check out The Prehab Deload.

You can never get enough Hartman…

Earlier this week, Bill Hartman provided us with seven great tips; here are eight more than certainly won’t disappoint!

8. Unilateral lower body training is well accepted, but unilateral upper body training is no less valuable and gets ignored by most trainers and coaches. It’s not uncommon for strength and conditioning coaches to recommend unilateral lower body exercises in an effort to maintain functional relationships in the trunk and hips. There are equally if not more important relationships between the upper extremity, the trunk, and the hips. Consider working toward developing the ability to perform a single-arm push-up as much as you develop your single-leg strength. It will go a long way toward maintaining your shoulder health and improve your performance.

9. It is a rare occasion that athletes needs complex training programs. Most athletes, regardless of level, are not well-trained strength athletes. Just as many HATE supplementary strength/performance training and don’t understand the value that it provides by allowing them to perform at their highest levels of performance. They would rather just play their sport. The exceptions are those athletes who have spent 3 to 4 years in a progressive, controlled, and properly designed strength program. Being advanced in a particular sport does not mean they are advanced in regard to supplementary training. When in doubt simplify.

10. If you choose to emphasize bench pressing in your training program, you need to spend more time strengthening your lower trapezius and rotator cuff.

The lower trapezius tends to be the weak point in your ability to stabilize the scapula and the rotator cuff is the big stabilizer for the glenohumeral joint. It is the ability to stabilize these areas that allows the larger prime movers to lift big weights. If these muscles don’t keep pace, your bench press will stall and you will most likely get injured.

11. Stand more and sit less. If you’re sitting on your ass, you’re not using it. If you’re not using it, you’ll forget how to use it when you train or play a sport. This can result in lower back pain, hip pain, or pain anywhere down the kinetic chain. You’ll also go a long way to prevent the loss of hip motion that will increase joint wear and tear and rob you of your athleticism at a premature age.

12. I recommend four recovery/restoration tools for everyone: sleep, food, soft-tissue work, and ice because they work for everyone.

I know a lot of things that have been used as recovery tools with world-class athletes. Most people are not world-class athletes and I question the value of many restorative tools. I’ve never been able to identify a measurable effect from something like a contrast shower other than shrinkage (you know what I mean). However, the four tools I recommend will apply to everyone.

Sleep is essential. The nervous system needs sleep to function at top efficiency. Food provides energy, reparative materials, and nutrient-based recovery. Soft-tissue work, whether it be massage, foam rolling, ART, or whatever, will maintain a more optimal condition of the soft-tissues. Trigger point, adhesions, and scar tissue affects mobility, tissue extensibility, and the ability to produce strength. An ounce of prevention goes a long way to assure optimal functional relationship between and within muscles and groups of muscles. Ice is under utilized by just about everyone. It is inexpensive and will go a long way to preserve your joint surface. Fifteen minutes of ice to heavily trained joints has been shown to have a preservation effect on joint cartilage.

13. Make your icing more effective by periodically moving the joint or muscle to which you’re applying ice. It promotes a more uniform application of the cold to the affected area. After you remove the ice, limit the motion of the affected area to preserve the cooling effect, as movement will increase rewarming.

14. Hip mobility affects more than you think. A lack of hip mobility will promote overuse of the lumbar spine to compensate for the lack of mobility. In patients with unilateral shoulder instability, almost half of those patients also showed poor hip mobility on the opposite side.

15. There are “money muscles” in almost every type of injury that when treated or activated immediately improve function. For shoulders, it’s the subscapularis. The subscapularis prevents the humeral head from moving forward and upward into the acromion in cases of impingement. Many times it’s overused due to repetitive movement, heavy loading, or both. Get it functioning again (ART does wonders) immediately restores shoulder function in a majority of cases.

For lower back pain, it’s the psoas. If someone has trouble forward flexing AND extending the spine (you can also see that they limit hip extension when they walk) check the psoas for spasm or adhesions. Restoring normal psoas function immediately restores spinal range of motion.

For lower back pain, it’s the psoas. If someone has trouble forward flexing AND extending the spine (you can also see that they limit hip extension when they walk) check the psoas for spasm or adhesions. Restoring normal psoas function immediately restores spinal range of motion.

For the knee, it’s the popliteus. Many times when rehabbing an athlete or patient with a knee injury, there’s sense of residual instability. Rather than going for the wobble board, consider checking the function of the popliteus. The popliteus assists in rotatory control of the knee. Restoring the popliteus function with soft-tissue work and a little strengthening often restores stability in no time.

About Bill

Bill Hartman is a physical therapist and strength and conditioning coach in the Indianapolis area. Bill is the co-creator of Inside-Out: The Ultimate Upper-Body Warm-up and a contributing author to Men's Health Magazine. He is also the creator of Your Golf Fitness Coach's Video Library, available at www.yourgolffitnesscoach.com. You can contact Bill directly via www.billhartman.net.

I’m off to Maine to lift some heavy stuff and see the family. Have a great weekend, everyone!

All the Best,

EC |

| Read more |

|

Yesterday morning, Tony Gentilcore and I got out to the local track to do some sprinting work. After we had wrapped up our 45-minute session, as we walked off the track, we noticed a 20-something year-old female runner on the ground banging out crunches in what we estimated were sets of 800.

What caught my eye even more than her elite training protocol (insert sarcastic smirk here), though, was a knee brace so large that it looked like a giant octopus had devoured her leg. Geek that I am, I started pondering things over.

Most people would say that she’s probably got an overuse injury from all the running. I wouldn’t disagree.

To take it a step further, though I immediately started thinking about why she had a dysfunction/ imbalance that could be predisposing her to pain with all that running.

Think about what happens with a crunch: trunk flexion.

As Mike Robertson and I described in our Building the Efficient Athlete DVD set, in the process, we actually make ourselves more kyphotic (rounded over at the upper back) via a shortening of the rectus abdominus, which pulls the rib cage down toward the pelvis. Just check out the points of attachment in the image below and you'll see what I mean:

In most cases, when we round over at the upper back, as a compensation to keep us upright, the lumbar spine tends to become more lordotic – meaning that the natural lumbar arch is exaggerated. Go to a more lordotic position, and you’ll “trigger” an increased amount of anterior pelvic tilt (associated with shortening/tightness of the hip flexors, including the rectus femoris, psoas, iliacus, tensor fascia latae, among others).

We know that the hip flexors play a very important role in knee health; the rectus femoris actually attaches to the patella, too. In addition to the pull these muscles have on the leg, they also tend to force one into anterior weight-bearing (already a problem in most females, thanks to evolution and high-heeled shoes).

Just imagine how great that knee would feel if she swapped the thousands of crunches for some foam rolling, lacrosse ball work, and glute activation and hip and ankle mobility drills. Success in training (and corrective exercise) is all about the opportunity cost of your training time and effort; you just need to select the drills that give you the most bang for your buck while ironing out imbalances that help you to move more efficiently.

Building the Efficient Athlete

Food for thought. Enjoy the rest of the week, everyone.

EC |

| Read more |

|

Seminar Stories

I wanted to start this newsletter off with a thank you to everyone who came out last weekend for the John Berardi seminar here in Boston. Dr. Berardi put on a great show, and the feedback has been fantastic. If you ever have the chance to see JB speak, don’t hesitate to jump at the opportunity.

Naked Nutrition

A few months ago, Mike Roussell sent me the preliminary version of his new project, The Naked Nutrition Guide. Mike went out of his way to contact several industry notables to go over this manual with a critical eye, and this feedback – combined with Mike’s outstanding knowledge of nutritional sciences – resulted in a fantastic finished product. There are bonus training programs from Alwyn Cosgrove, Nate Green, and Jimmy Smith. Check it out for yourself:

The Naked Nutrition Guide

Female Fitness

Last week, Erik Ledin of Lean Bodies Consulting published Part I of an interview he did with me on female training. Check it out:

EL: First off, thanks for agreeing to the interview. We've known each other for a number of years now. I used to always refer to you as the "Anatomy Guy." You then became know for being "The Shoulder Guy" and have since garnered another title, "The Mobility Guy." Who is Eric Cressey?

EC: Good question. As you implied, it's the nature of this industry to try to pigeonhole guys into certain professional "diagnoses." Personally, even though I specialize in athletic performance enhancement and corrective exercise, I pride myself on being pretty well-versed in a variety of areas - endocrinology, endurance training, body recomposition, nutrition, supplementation, recovery/regeneration, and a host of other facets of our industry. To some degree, I think it's a good thing to be a bit all over the place in this "biz," as it helps you to see the relationships among a host of different factors. Ultimately, I'd like to be considered a guy who is equal parts athlete, coach, and scholar/researcher.

All that said, for the more "traditional answer," readers can check out my bio.

EL: What are the three most underrated and underused exercises? Does it differ across gender?

EC: Well, I'm not sure that the basics - squats, deadlifts, various presses, pull-ups, and rows - can ever be considered overrated or overappreciated in both a male and female population.

Still, I think that single-leg exercises are tremendously beneficial, but are ignored by far too many trainers and lifters. Variations of lunges, step-ups, split squats, and single-leg RDLs play key roles in injury prevention and development of a great lower body.

Specific to females, we know that we need a ton of posterior chain work and correctly performed single-leg work to counteract several biomechanical and physiological differences. Namely, we're talking about quad dominance/posterior chain weakness and an increased Q-angle. Increasing glute and hamstrings strength and optimizing frontal plane stability is crucial for resisting knock-knee tendencies and preventing ACL tears. If more women could do glute-ham raises, the world would be a much better place!

EL: What common issues do you see with female trainees in terms of muscular or postural imbalances that may predispose them to some kind of injury if not corrected? How would you suggest they be corrected or prevented?

EC:

1. A lack of overall lower body strength, specifically in the glutes and hamstrings; these shortcomings resolve when you get in more deadlifts, glute-ham raises, box squats, single-leg movements, etc.

2. Poor soft-tissue quality all over; this can be corrected with plenty of foam rolling and lacrosse/tennis ball work.

3. Poor core stability (as much as I hate that word); the best solution is to can all the "turn your lumbar spine into a pretzel" movements and focus on pure stability at the lower back while mobilizing the hips and thoracic spine.

4. General weakness in the upper body, specifically with respect to the postural muscles of the upper back; we'd see much fewer shoulder problems in females if they would just do a LOT more rowing.

EL: You've mentioned to me in the past the issues with the ever popular Nike Shox training shoe as well as high heels in women. What's are the potential problems?

EC: When you elevate the heels chronically - via certain sneakers, high-heels, or any other footwear - you lose range of motion in dorsiflexion (think toe-to-shin range of motion). When you lack mobility at a joint, your body tries to compensate by looking anywhere it can to find range of motion. In the case of restricted ankle mobility, you turn the foot outward and internally rotate your lower and upper legs to make up for the deficit. This occurs as torque is "converted" through subtalar joint pronation.

As the leg rotates inward (think of the upper leg swiveling in your hip joint socket), you lose range of motion in external rotation at your hip. This is one of several reasons why females have a tendency to let their knees fall inward when they squat, lunge, deadlift, etc. And, it can relate to anterior/lateral knee pain (think of the term patellofemoral pain ... you've got restriction on things pulling on the patella, and on the things controlling the femur ... it's no wonder that they're out of whack relative to one another). And, by tightening up at the ankle and the hip, you've taken a joint (knee) that should be stable (it's just a hinge) and made it mobile/unstable. You can also get problems at the hip and lower back because ...

Just as losing range of motion at the ankle messes with how your leg is aligned, losing range of motion at your hip - both in external rotation and hip extension - leads to extra range of motion at your lumbar spine (lower back). We want our lower back to be completely stable so that it can transfer force from our lower body to our upper body and vice versa; if you have a lot of range of motion at your lower back, you don't transfer force effectively, and the vertebrae themselves can get irritated. This can lead to bone problems (think stress fractures in gymnasts), nerve issues (vertebrae impinge on discs/nerve roots), or muscular troubles (basic strains).

So, the take-home message is that crappy ankle mobility - as caused by high-top shoes, excessive ankle taping, poor footwear (heel lifts) - can cause any of a number of problems further up the kinetic chain. Sure, we see plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinosis, and shin splints, but that's just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what can happen.

How do we fix the problems? First, get out of the bad footwear and pick up a shoe that puts you closer in contact with the ground. Second, go barefoot more often (we do it for all our dynamic flexibility warm-ups and about 50% of the volume of our lifting sessions). Third, incorporate specific ankle (and hip) mobility drills - as featured in our Magnificent Mobility DVD.

Oh, I should mention that elevating the heels in women is also problematic simply because it shifts the weight so far forward. If we're dealing with a population that needs to increase recruitment of the glutes and hamstrings, why are we throwing more stress on the quads?

Stay tuned for Part II - available in our next newsletter.

Have a great week, everyone!

EC |

| Read more |

|

This week, we've got Part 2 of the Alwyn Cosgrove fat loss interview along with a few quick announcements.

Just a quick note, first: I had my first article published at Active.com just recently. Check it out:

Must-Have Weight Room Movements for Cyclists: Part 1

EricCressey.com Exclusive Interview with Alwyn Cosgrove: Part 2

Last week, Alwyn tossed out a ton of great information with respect to fat loss programming, but he's not done yet! Without further ado, let's get to it...

EC: As a mobility geek, I was intrigued when I heard you mention that you felt that corrective exercise - especially in the form of mobility and activation work - had merits with respect to utilizing compound movements to create a metabolic disturbance. Could you elaborate?

AC: If you think about the fiber recruitment potential, the answer is pretty obvious. Even if you're using compound movements to create that metabolic disturbance, if your muscles were not activated like they should be, you still are not creating as big as a disturbance as you could.

For example, squats and deadlifts will give you more bang for your buck if your glutes are active than if they aren't. Many of the movements from your Magnificent Mobility DVD - supine bridges and birddogs, for example, with respect to the glutes - are great pairings for more of these compound lifts if you're looking to create more of a metabolic disturbances. In the upper body, you might pair chin-ups with scap pushups, or bench presses with scapular wall slides.

And, to add on the above points, you can ignore the value of that mobility and activation work when it comes to preventing injury. Many times, form will start to break down with some of the longer time-under-tension prescriptions in more metabolically demanding resistance training protocols. When you get things firing the way they should, you immediately make these complexes and circuits safer.

EC: Great points. Now, you bust my chops for being a guy that reads the research on a regular basis, but we both know that you’re as much of a “research bloodhound” as I am. As such, I know that you’ve got some ideas on the “next big thing” when it comes to fat loss. Where do you feel the industry will be going along these lines in the years to come? Here’s your chance to make a bold prediction, you cocky bastard.

AC: Ok – you’re putting me on the spot here.

If you don’t drink water – what happens? Your body immediately tries to maintain homeostasis by retaining water – doing the opposite.

Does weight training build muscle? No. It destroys muscle and the body adapts by growing new muscle. The body adapts by homeostasis – trying to regain balance by doing the opposite.

If we look at aerobic training – and look at fat oxidation – we can see that fat oxidation increases at 63% V02 max. We burn fat during the activity. How does that EXACT SAME BODY respond? Hmmmm...

What cavemen survived the famine in the winters? The cavemen that stored bodyfat efficiently. We have evolved into a race of fat storing machines.

We are aerobic all day. If aerobic training worked – then we wouldn’t need to work harder would we? When we work harder we see a trend – we lose fat – but is it because we are moving towards anaerobics?

My prediction is that as we understand more and more about the science of losing fat (which in reality we haven’t really studied in any depth) I think we’ll find that excessive aerobic training may retard fat loss in some way.

I’ve been saying for years that I don’t think it helps much. And the studies support that. I’m now starting to feel that it may hurt.

How many more studies have to come out that show NO effect of aerobic training to a fat loss program before we’ll recognize it?

DISCLAIMER – I work with endurance athletes. I work with fighters. I am recovering from an autologous stem cell transplant and high dose chemotherapy. I think aerobic training is extremely helpful. But not as a fat loss tool.

EC: Excellent stuff as always, Alwyn. Thanks for taking the time.

I can't say enough great things the fat loss resources Alwyn has pulled together; I would strongly encourage you all to check them out: Afterburn.

All the Best,

EC

All the Best,

EC |

| Read more |

|

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|