Coordination Training: A Continuum of Development for Young Athletes

Today’s guest blog comes from Brian Grasso, the director of the International Youth Conditioning Association.

The myths and falsehoods associated with coordination training are plenty. I’ll outline the “Top 3” here:

1. Coordination is a singular element that is defined by a universal ability or lack of ability

2. Coordination cannot be trained nor taught

3. Coordination-based stimulus should be restricted to preadolescent children

This article will provide a broad-based look at each of those myths and shed some light on the realities behind coordination training as a continuum for the complete development of young athletes aged 6 – 18.

1. Coordination & Young Athletes

Largely considered a singular facet of athletic ability, it is not uncommon to hear coaches, parents or trainers suggest that a given young athlete possess “good” or “bad” coordination.

This generalization does not reflect the true nature of the beast, or specific features that combine to create coordination from a macro-perspective. Coordination is, in reality, comprised of several different characteristics:

- Balance – a state of bodily equilibrium in either static or dynamic planes

- Rhythm – the expression of timing

- Movement Adequacy – display of efficiency or fluidity during locomotion

- Synchronization of Movement – harmonization and organization of movement

- Kinesthetic Differentiation – the degree of force required to produce a desired result

- Spatial Awareness – ability to know where you are in space and in relation to objects

While many of these traits have great overlap and synergy, they are unmistakably separate and can, in fact, be improved in relatively isolated ways. That’s not to suggest that your training programs should necessarily look to carve up the elements of coordination and work through them in a solitary manner. Just a notation intended to show that coordination as it relates to young athletes can be improved at the micro level.

2. Coordination – Can You Teach Young Athletes?

The answer, in short, is yes.

Coordination ability is not unlike any other biomotor; proficiencies in strength, speed, agility and even cardiovascular capacity (through mechanical intervention) can be taught, and at any age.

The interesting caveat with coordination-based work, however, is that its elements are tied directly to CNS development and therefore have a natural sensitive period along a chronological spectrum. The actuality of sensitive periods tends to be a contentious topic amongst researchers and many coaches. Some of these individuals are not satisfied with current research and are therefore not eager to believe in their existence and others who accept sensitive periods of development to be perfectly valid. It’s worth pointing out that I am in no way a scientist or researcher, but have read numerous books and research reviews on the subject and feel satisfied that they do exist and can be maximized (optimized for a lifetime) through proper stimulus.

This “optimization” issue is the true crux of the matter. Especially during the very early years of life (0 – 12 years) the CNS contains a great deal of plasticity, or ability to adapt. This plastic nature carries through the mid-adolescence, but then significantly decreases from there. Many mistake this point as an implication that the human organism cannot learn new skills in any capacity once their CNS has passed the point of being optimally plastic, but this is not true. Skill of any athletic merit can be learned at virtually any age throughout life. What the plasticity argument holds is that these skills could never be optimized if they were not introduced at a young age.

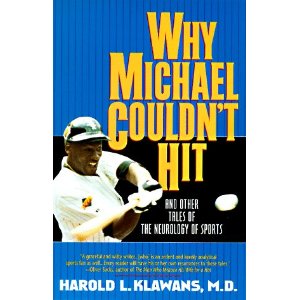

Why Michael Couldn’t Hit: And Other Tales of The Neurology of Sports is a fascinating book by Dr. Harold Klawans. Klawans presents a review of his prediction that Michael Jordan, one of the greatest athletes of all time, would not become an extraordinary baseball player during his attempts to do so with the Chicago White Sox.

Dr. Klawans contented that because Jordan did not learn or practice the specific motor and hand-eye aspects of hitting baseballs when he was young, no matter how great an athlete he was, he would never be able to do so at an advanced level.

Inevitably, Dr. Klawans was correct.

The case for neural plasticity suggests that during the formative years of growth, it is imperative that young athletes be introduced to all types of stimulus that fuel improvement to the elements of coordination listed earlier. This is one of the very critical reasons that all young athletes should play a variety of sports seasonally and avoid any sort of “sport specific” training. Unilateral approaches to enhancing sport proficiency will meet with disastrous results from a performance standpoint if general athletic ability, overall coordination and non-specific load training is not reinforced from a young age.

This bring us to the final myth…

3. Teenage Athletes Are ‘Too Old’

Now, while there is truth to the matter that many of the sensitive periods for coordination development exist during the preadolescent phase of life, it would be shortsighted to suggest that teenage athletes should not be exposed to this type of training.

Firstly, much of the training of coordination takes the form of injury prevention. Any sort of “balance” exercise, for example, requires proprioceptive conditioning and increases in stabilizer recruitment. With “synchronization of movement,” large ROM and mobility work is necessary. “Kinesthetic differentiation,” by definition, involves sub-maximal efforts or “fine-touch” capacity that is a drastically different stimulus than most young athletes are used to in training settings.

Beyond that, there is the matter of motor skill linking. According to Jozef Drabik, as much as 60% of the training done by Olympic athletes should take the form of non-direct load (i.e. non-sport-specific). To truly stimulate these rather advanced athletes however, one option (which is a standard during the warm-up phase of a training session) is to link advanced motor skills (coordination exercises) together creating a complex movement pattern.

For example:

Run Forward —> Decelerate —> 360 Jump —> Forward Roll —> Tuck Jump

Or

Scramble to Balance —> 1-Leg Squat —> A Skips —> Army Crawl —> Grab Ball/Stand/Throw to Target

In each of these patterns, we have represented:

- Spatial Awareness

- Synchronization of Movement

- Balance (dynamic and static)

- Movement Adequacy

- Kinesthetic Differentiation

- Rhythm

I have used warm-up sequences just like these with high school, collegiate and professional athletes from a variety of sports.

Brian Grasso has trained more than 15,000 young athletes worldwide over the past decade. He is the Founder and CEO of the International Youth Conditioning Association – the only youth-based certification organization in the entire industry. For more information, visit www.IYCA.org.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Newsletter: