Why We Shouldn’t Compare Kids in Sports

One of the more concerning trends I’m seeing on the youth sports scene is the how often the youngest kids are compared to their peers. This is an issue among programs monetizing sports participation, coaches responsible for identifying/developing proficiency, and parents concerned that their kids are falling behind.

I’m somewhat uniquely positioned to speak on this because I’ve been involved on the development of 12-year-olds who’ve eventually become professional athletes. And, more importantly, I’m a parent of three daughters. The older two, Lydia and Addison, are 10-year-old twins.

The most important lesson you learn as a twin parent is that people will always think saying “double trouble” is hilarious even though it’s incredibly hackneyed. Once you move past that, though, lesson #2 is more actionable: you should never try to compare your twins to one another.

This was obvious even when they were in the womb. When we’d go to ultrasounds, Lydia was front and center; we joked that she had her face pressed against the glass. Meanwhile, it would always take the technician and bunch of time to find Addison, who was always “hiding.” At one ultrasound, all we could see was the bottom of her foot.

When they were born, out came a brunette with olive skin (Lydia looks like her mom) and a strawberry blonde with a lighter complexion (Addison is a sunburn waiting to happen, just like dad).

Lydia came out screaming and ready to take on the world. Addison struggled a bit and needed four days in the NICU with oxygen and a feeding tube. Lydia was a feisty baby and always wanted her mother, and Addison was super mellow and could usually be found in dad’s arms while mom was holding her sister.

At 18 months, they flip-flopped. Lydia became the rule follower, and Addison started giving us attitude. Lydia ate just about everything we put in front of her, yet Addison’s taste buds refused to recognize the existence of all but about five foods.

Lydia walked five months before Addison (who was a little taller/heavier) did. Addison picked up swimming faster than Lydia. Lydia swings a bat right handed, while Addison does so lefty. Lydia was reading chapter books while Addison was still working on sight words. Addison, on the other hand, thrived with math relative to her sister.

Lydia is faster; Addison is stronger. Lydia listens intently and has picked up more “coaching intensive” sports like tennis, softball, and gymnastics quickly. Addison, on the other hand, is a bit of a space cadet in the field at soccer games; she’s kicking grass and watching adjacent fields. Conversely, she’s in her element with creative initiatives like music, art, and dance. She reads all the time – to the point that we actually have to ask her to put away her book at the dinner table at just about every family meal.

I develop athletes for a living, and I can tell you without wavering that I have zero clue what sports my kids will enjoy doing next week, let alone years from now. Our twins have spent 99% of their lives together since conception and are completely different now, and we’ve seen unpredictable iterations of them to get to this point.

We don’t predict athletic success well at all. We don’t even predict what sports kids will enjoy well. You’d be amazed at how many professional athletes weren’t child prodigies or even standout middle school athletes. Let’s face it: puberty makes a lot of coaches look much smarter than they are!

In other words, the ONLY thing we can control is enriching their experiences in these sports while they’re participating – and comparisons don’t do that. What does work?

First, praise effort over outcomes. The reps – and the fun that comes with executing them with teammates/friends – are what matter. I can’t tell you a single score from one of my little league games, but I could write a book about an a**hole coach I had who took things way too seriously. In hindsight, he really didn’t know much about baseball, either.

Second, celebrate novelty. It gets kids excited, and participating in a variety of sports at a young age provides a rich proprioceptive environment that cultivates an invaluable athletic foundation upon which specific skills can later be built. This broad athletic foundation includes variability in planes of motion, speed of movement and the forces involved. Collectively, these exposures teach athletes to distribute stress over multiple joints and avoid overuse injuries at specific segments.

Third, appreciate that random practice outperforms blocked practice over the long-term when it comes to skill acquisition. Mix in a variety of drills and fluctuate the order and duration of them, then integrate fun competitions with them.

Fourth, recognize the importance of in-season and off-season periods. This fluctuation of the seasons helps keep kids from getting bored with certain sports, but also facilitates graduated exposures to stressors. A 10-year-old throwing a baseball 12 months out of the year is a terrible idea; playing some soccer and hoops is a great way to stay active while developing in different ways.

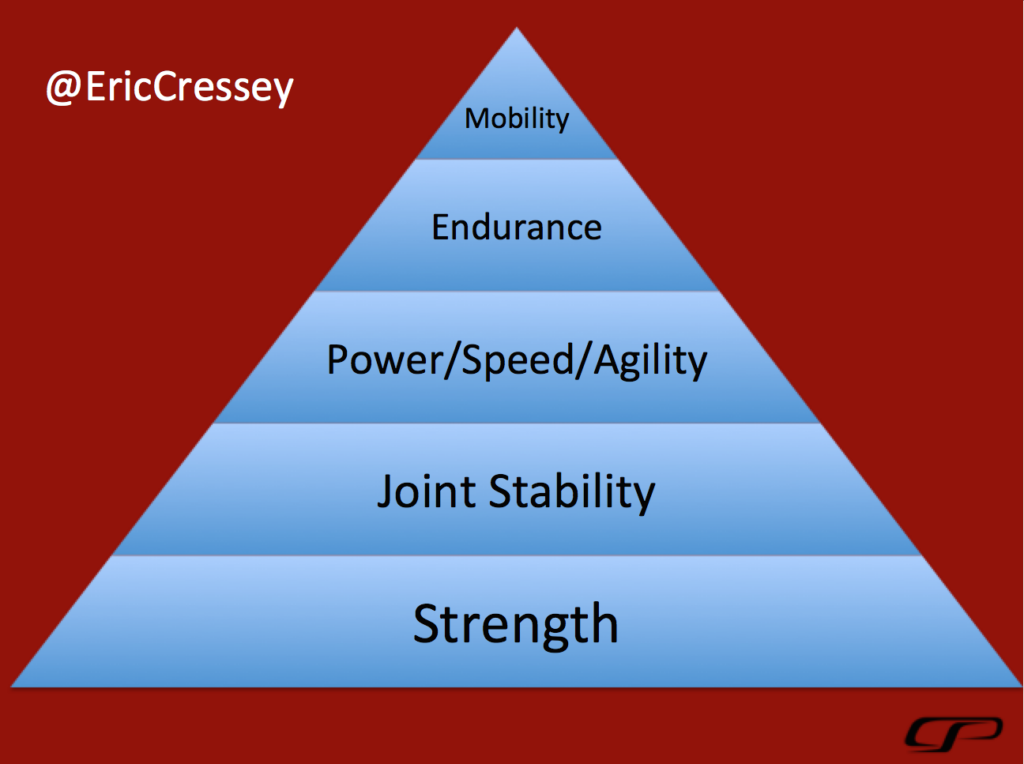

Fifth, as soon as a kid is mature enough for it, get them involved in a foundational strength training program. It’ll have a “trickle-down” effect to a variety of athletic qualities while reducing their risk of injury. Again, it has to be fun, just like everything else!

Summarily, don’t compare kids; instead, appreciate that they’re all unique and develop at different rates and in different ways. Youth sports is all about instilling a passion for the game, enjoying a sense of community, and fostering a positive lifelong relationship with exercise.