Pelvic Arch Design and Load Carrying Capacity (Or, How the Heck Does EC Deadlift So Much?)

Today’s guest post comes from Dean Somerset. In reviewing his outstanding resource, The Complete Shoulder and Hip Blueprint (which is currently on sale for $100 off), I loved the section Dean devoted to pelvic structure as it relates to our ability to handle heavy weight training. I asked if he’d be willing to expand on the topic in a guest post, and he kindly agreed. I really enjoy Dean’s work and think you will, too. – EC

I love the deadlift, but it doesn’t love me back all that much. I can pull about 455 on a good day at a body weight of 230, but I haven’t tested a max pull in a few months. I just finished training for a kettlebell course, so it would be interesting to see if it’s gone up at all without specific deadlift training but more accelerative training, but that’s neither here nor there, nor is it relevant to today’s post. It’s just a cool thought.

One reason why I am at the mercy of the deadlift is a previous injury to my right sacroiliac (SI) joint. This causes the arch structure of the pelvis to be compromised, and limits my ability to withstand the shear forces of a heavy deadlift.

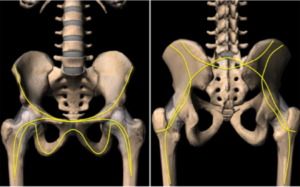

Arch structures are an integral feature of a lot of architectural structures, and for good reason. They help to disburse compressive loads across a span towards abutments on either side of the span. Think of ancient Roman aqueducts, bridges, or even more contemporary structures such as the arch in St Louis.

The ability to withstand compressive forces and maintain a powerful structure is so impressive in an arch structure that many ancient arches were constructed without the use of mortar between the joints of the stones. This compressive resistance is of massive importance not only in buildings, but in our own anatomy.

The pelvis is essentially an amazing structure that’s a composite of a single bone made of dozens of noticeable arch structures that integrate between the left and right sides, using the sacrum as the keystone.

As the pelvis and its arches form a span between the two abutments of the legs, it allows for a tremendous amount of compressive force to be relatively easily dispersed across it with relative ease.

The downside to an SI joint injury comes when in the bottom position of the deadlift, or any forward flexed position for that matter, as the arch structure runs directly across the back of the SI joint and it is required to be completely and perfectly integrated, much like the keystone in an arched doorway. If not, the structure comes down.

Now, I have some theories as to how you could use genetics to your advantage to lift heavy weights, as well as some observations about our mutual good friend Eric here as to why that bugger can pull so much weight, training, diet, and focus aside (hey, we all know he’s a cyborg, but there’s some advantages that a solid work ethic can’t provide everyone). A lot of it depends on how much compressive stress your pelvis can manage.

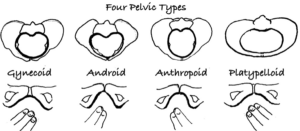

First, there are four different types of pelvis when looking at the width, breadth and angulations of the sit bones (technically known as the ischial tuberosities). This is important because the wider and shorter the arches, the less likely they can sustain during crazy heavy loadings. The best hips for heavy vertical loading are narrow and deep.

The Android and Anthropoid hip positions are the most favorable for pulling a sick deadlift off the floor, whereas the wider and shallower gynecoid and platypelloid hips would most likely result in an epic fail and probably injury.

It should come as no surprise to anyone who reads EricCressey.com that there are different types of pelvises (pelvii?). He’s mentioned a lot that there are different types of acromions in the shoulder and that specific angulations would affect rotator cuff function and risk of shoulder impingement. Everyone has different joints and bones, and it’s the combination of these that allows for some of us to do specific things that others can’t. For instance, I can get my hips way wider and longer in the sagittal and frontal plane than most people can, which means mobility isn’t a problem, regardless of what amount of stretching I do.

As a result of my pelvic angles, I’ve got that on lock down. Conversely, loading through a hip flexed sagittal plane loading means I have to brace like no ones business and use some of my active tissues as passive restraints instead of as drivers for the weight. The form closure of the joint is less effective with a wider pelvis than in a narrower one, and the form closure has to work harder, meaning the amount of weight I can pull is less than optimal, and the amount of weight Eric can pull makes grown men weep and kick walls in frustration.

However, it also means he has some minor issues getting unrestricted mobility outside of the sagittal plane. This video shows a very subtle restriction to femoral external rotation during abduction. Check out the kneecap of the extended leg.

Here’s another view of the same leg, but with a similar movement.

Hey, I’ve got a ton of my own movement restrictions, just like everyone else. Check this action out:

That was terrible! But did you see my earlier Cossack squat? Like a boss.

Eric owns sagittal plane, potentially due to a stacked pelvis that’s designed to bear weight like no ones business. However, in nature you typically don’t see the combination of excellent characteristics. In many cases the yin of mobility is in sharp contrast to the yang of max strength. For liner force production, the guy’s one of the best in the world hands down.

I can hit up lateral mobility like a champ, but sagittal force production is an issue.

So how would you assess each of us to develop a program that would help each of us, given our unique capabilities and hindrances? Would you focus on working towards building up the weakness in an isolative manner (as many corrective strategies employ) or would you look to hit up more of an all-encompassing manner, where we could still use our strengths to our advantage and make progress, without feeling like minor restrictions were a big issue?

I’d rather train like a beast than do stuff that may or may not provide much benefit based on my hip positioning and the arch structure of my specific anatomy any day of the week, so having a big tool box to draw from can make or break a program that gets both of us excited to train and fist pump like champs, which means we’re both going to be more likely to see it through to the end and get some sick gains.

The simple difference could be having me do way more loaded carries to use loading without exposing my spine to as much shear forces, as well as sagittal plane stabilization exercises like front planks and anti-extension presses. For Eric, it may mean using a lot more lower load hip rotational movements that still challenge the core, such as low crawl patterns a la Ido Portal.

Follow this up with stupid amounts of loading through sagittal plane dominant movements and he’d be a champ fo’ sho’.

At the end of the day, programming for the individual is most effective when you balance the “yin and yang” of their strengths and weaknesses, but understand the structural benefits the individual may have available to them, as well as the restrictions. Having a broad hip structure versus a narrower structure can be the difference between someone who loves deadlifts versus someone who wants to hit up rotational drills all day long. Having the tools to assess and develop an awesome program for them can be the difference between being a good trainer and a great trainer.

Looking for more great information like this? Check out Dean and Ton Gentilcore’s product, The Complete Shoulder and Hip Blueprint. It’s on sale through Wednesday for $100 off, and includes tons of fantastic information.