Youth Strength and Conditioning Programs: “He’s a Big, Strong Kid.”

Recently, while discussing one particular athlete we encountered at Cressey Sports Performance, my staff members and I got on the topic of how it’s more of a challenge to train bigger (taller and heavier) young athletes than it is to work with smaller guys. Interestingly, the challenges come less from the actual physical issues they present and more from the social expectations that surround their size. Here are seven reasons why I cringe when I hear parents say “he’s a big, strong kid” when describing their children on the phone.

1. Bigger kids are often forced into sports and positions that may impede their long-term development – When you’re the heavy kid, you’re automatically pushed toward football and put on the line. If you’re playing baseball, it’s first base or catcher. If it’s basketball, you’re the power forward. You get the picture – and similar “pushes” are made on tall kids to play basketball or volleyball. The problem is that in most cases, these sport and positional “predispositions” put bigger kids in situations where they don’t develop in a broad sense because there simply isn’t enough variety.

2. Bigger kids usually start weight-training on their own – This point relates closely to point #1. Unfortunately, when you’re already labeled as the next star offensive lineman or power forward and you can already push your buddies around, chances are that you learned to lift with Dad in the basement, from a misinformed football coach, or be screwing around with your buddies. I would much rather have a completely untrained 16-year-old start up with me than be presented with a 16-year-old with years of poor strength and conditioning programs and coaching under his belt. This is true regardless of body type, but especially problematic in bigger kids for reasons I outline below.

3. “Strong” has different meanings – Sports require a combination of absolute and relative strength. Strength is also highly specific to the range of motion (ROM) in which one trains. There is also a difference between concentric and eccentric strength.

What do most big young athletes do when left on their own? Focus heavily on absolute strength (train what they’re good at) through small ROMs (rather than fight their bodies) with concentric-heavy workloads (because pushing a blocking/tackling sled is sexier than a properly executed lunge).

I can count on one hand the number of teenage athletes who were called “big and strong” who have actually showed up on their first day and demonstrated any appreciable level of strength in any context – let alone usable strength that will help them in athletic endeavors. Usually, we wind up seeing a sloppy 135-pound bench press with the elbows flared, legs kicking, bar bouncing off the chest…in a kid who can’t do a push-up.

And this is where the problem arises: kids who have always been told they were strong don’t like coming to the realization that they really aren’t strong. We don’t have to directly tell them, either; taking them through basic strength exercises with proper form will reveal a lot. And, there is typically an example of a smaller athlete like this kicking around not too far away.

The kids who check their egos at the door will thrive. A lot might never come back until they’re injured from poor body control or riding the pine because it turns out that their “strengths” really weren’t that strong.

4. Bones grow faster than muscles and tendons – In young athletes who haven’t gone through the adolescent growth spurt, you often don’t have to do any additional static stretching, as a dynamic warm-up and strength training program through a full ROM can cover all their mobility needs. Unfortunately, when kids grow quickly, the bones lengthen much faster than the muscles and tendons do, so we run into situations where bigger kids have truly short (not just stiff) tissues. Effectively, this adds one more competing demand for their time and attention – and it’s the worst kind to add, as most kids hate to stretch.

5. Being bigger changes one’s stabilization strategy – As I described in great detail in The Truth About Unstable Surface Training, the taller one is, the further the center of gravity is away from the base of support. As such, taller kids are inherently more unstable than shorter kids – although this can be partially remedied by gaining muscle mass in the lower body to lower the COG and learning to “play lower” in appropriate situations.Not surprisingly, though, being heavier – particularly with respect to having a belly – can dramatically change one’s stability as well. Carrying belly fat shifts the center of gravity forward – which is why individuals with this “keg” instead of a six-pack appear more lordotic (excessively arched at the lower back). Compensations for this occur all along the kinetic chain, but the two things I’d highlight the most are:

a. An increased need for anterior core strength – As evidenced by the high incidence of spondylolysis (lumbar spine fractures) and how badly most kids perform on basic prone bridging and rollout challenges, the inability to resist lumbar hyperextension (and excessive rotation) is a serious problem. The bigger the belly, the more extended the lumbar spine will be. Just ask any pregnant woman how her back feels during the last trimester.

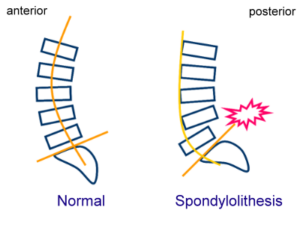

b. Substitution of lumbar (hyper)extension for hip extension – You’ll see a lot of big-bellied kids who can’t fully extend their hip and instead just arch their back to get to where they need to be. This is a problem on multiple fronts. First, the hip extensors are far stronger and more powerful than the lumbar extensors, so performance is severely impaired. Second, there are huge injury implications both chronically (lumbar stress fractures, hip capsule irritation) and acutely (strained rectus femoris or hamstrings).

Simply dropping some body fat and improving anterior core strength is a huge game-changer for many overweight athletes. It’s not always the answer they want to hear.

6. Bigger kids usually have less work capacity – I’ve never been a guy who jumped on the work capacity bandwagon, as I feel that it’s very activity-specific. However, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to observe that the more body fat one carries, the more work he’ll do oxygenating useless tissue, and the less oxygen he’ll get to working muscles. More importantly, though, try doing your next training session with a 60-pound weight vest on and see what it does to your work capacity.

The lower the work capacity, the less quality work one can accomplish in a strength and conditioning program. Gains simply don’t come as quickly on the strength and fitness side of things – even if body fat is pouring off heavier athletes. In other words, they’ve actually sacrificed one window of adaptation (athletic development) in order to make another one (fat loss) larger.

7. I speculate that bigger athletes have an increased prevalence of “subclinical” musculoskeletal pathologies/deviations from normalcy – I’ve written in the past about how many athletes are just waiting to reach threshold because their MRIs and x-rays look terrible – even if they are completely asymptomatic. You can see this just about anywhere in the body; most basketball players are just waiting for patellar tendinosis to kick in, and many football lineman are teetering on the brink of a lumbar stress fracture or spondylolisthesis (or both).

The heavier one is – especially in the presence of insufficient relative strength, as noted above – the more pounding one will place on the passive restraints such as the meniscus, intervertebral discs, and labrum. A bigger belly and the resulting lordosis will drive more anterior pelvic tilt, femoral/tibial internal rotation, and pronation. How would you like to be the plantar fascia or Achilles tendon in this situation?

Tall athletes tend to slouch more because they have to look down at all their peers. Get more kyphotic, add some scapular dyskinesis, and see what happens to the rotator cuff, labrum, and biceps tendon over time.

There are countless examples along these lines. And, to make matters worse, obese individuals are more likely to have inaccurate diagnostic imaging. In an interview I did with radiologist Dr. Jason Hodges, he commented:

By far, the biggest limitation [to diagnostic imaging] is obesity. All of the imaging modalities are limited by it, mostly for technical reasons. An ultrasound beam can only penetrate so far into the soft tissues. X-rays and CT scans are degraded by scattered radiation, which leads to a higher radiation dose and grainy images. Also, the time it takes to do the study increases, which gives a higher incidence of motion blur.

I want to be very clear; I love dealing with bigger kids just like I do all my other athletes. We don’t lock them in a closet with celery sticks and an exercise bike; we work them hard, but make training fun and support them fully in their quest to fulfill their athletic potential. Having been an overweight teenage athlete myself, I know that weight management in young athletes is a hugely sensitive subject that must be approached with extreme care.

I also know, however, that in my overweight years, I would have much rather been worked hard like the other athletes and given the opportunity to choose my sport and position of interest rather than pigeonholed into one specific avenue because of my build. That’s where the “big, strong kid” label really concerns me and makes me want to plan out my strategy – both in terms of the physiological and social approach to training – very carefully.