Coaching Cues to Make Your Strength and Conditioning Programs More Effective – Installment 5

Today marks the fifth installment of a series that looks at the coaching cues we use at Cressey Sports Performance. Here are three more cues we find ourselves using with our athletes all the time.

1. Move the hands in or out to improve your deadlift technique.

When you’re learning how to deadlift, understanding hand positioning is really important – but each deadlift variation is unique in terms of what you have to do with your grip. Check out this video to understand why:

2. Squat between your legs instead of over them.

In the past, I’ve spoken at length about how stance width impacts where the knees go. Move the feet out too wide, and the knees have no place to go but in. Bring them in closer, and it’s much easier to get the knees out. Check out this video for more details:

So, for many folks, bringing the feet in can really help – particularly with the deadlift. However, squats can be a bit trickier, as the stance coming in can lead to a lot more forward lean and individuals not positioning the torso correctly. Individuals will squat as if they are trying to touch the belly to the quads. There are, in fact, some accomplished lifters who do this, but their bellies are very big, and the Average Joe isn’t fat enough to pull this mechanical advantage off! Most folks wind up turning this approach into a really ugly good morning.

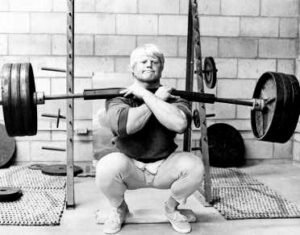

This is why I like the cue of telling folks to squat between the legs instead of over the top of them. Some people grasp it a lot better than “spread the floor” or “knees out.” They can also understand positionally if you show them a bad set-up followed by a good set-up, like this classic photo (notice how the knees around outside the torso from the rear view):

Source: DaveDraper.com

3. Pretend your biceps is a rotisserie chicken.

This is, without a doubt, the strangest cue I’ve given. However, it works.

When we’re doing our (shoulder) external rotation variations, we want to make sure the humeral head (ball) is centered in the glenoid fossa (socket), as that is the primary functional of the rotator cuff. This cue gets the job done:

Looking for more detailed coaching tutorials like this? Check out Elite Training Mentorship, an extensive online education program that features my staff in-services, exercise demonstrations, and articles – as well as the contributions of several other accomplished fitness professionals.