3 Thoughts for Getting the Glutes Going

Recently, I box squatted for the first time in a few months – and the posterior chain soreness I felt got me thinking about the functional anatomy in play, particularly with respect to the glutes. Here’s what’s rattling around my brain on that front (warning: functional anatomy heavy nerd post ahead).

1. People think of the gluteus maximus too much as a hip extensor and not enough as a posterior glider of the femoral head.

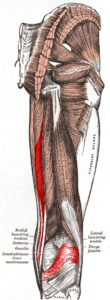

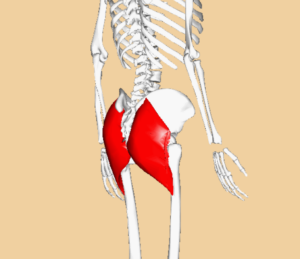

The gluteus maximus is an important prime mover of the hip – especially into hip extension. However, it’s also a crucial stabilizer. The other hip extensors – hamstrings and adductor magnus – have inferior attachment points lower down on the femur.

Meanwhile, the gluteus maximus actually inserts higher up – right near the femoral head.

The result is that when you extend your hips with the hamstrings and adductor magnus, the head of the femur can glide forward in the socket and irritate the front of the hip. When you get adequate gluteus maximus contribution, it helps to reduce this anterior stress. In many ways, the glutes work as a rotator cuff of the hip (while the hamstrings and adductor magnus act like the lats and pecs, respectively).

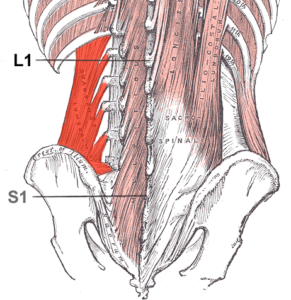

2. Glute activation can be a game changer with respect to chronic quadratus lumborum (QL) tightness – but only if you perform exercises correctly.

Shirley Sahrmann and her disciples have frequently observed that whenever you see an overworked muscle, you should always look for a dysfunctional synergist. A common example at the shoulder is a cranky biceps tendon picking up the slack for an ineffective rotator cuff.

Quadratus lumborum fits the bill in the core/lower extremity because its attachment points unify the pelvis, lumbar spine, and ribs.

When it shortens, it pulls the spine into lateral flexion and the lumbar spine into extension. In other words, it can give you “fake” hip abduction and hip extension – both of which come from the glutes. Whether you’re doing mini-band sidesteps, side-lying clams, or loading your hips in a pitching delivery, you need to make sure the movement is happening at the ball-socket (femoral head – acetabulum) rather than at the spine. And, when you’re doing your prone hip extension, supine bridges, hip thrusts, and deadlifts, you want to make sure you’re getting true hip extension and not just extra low back arching.

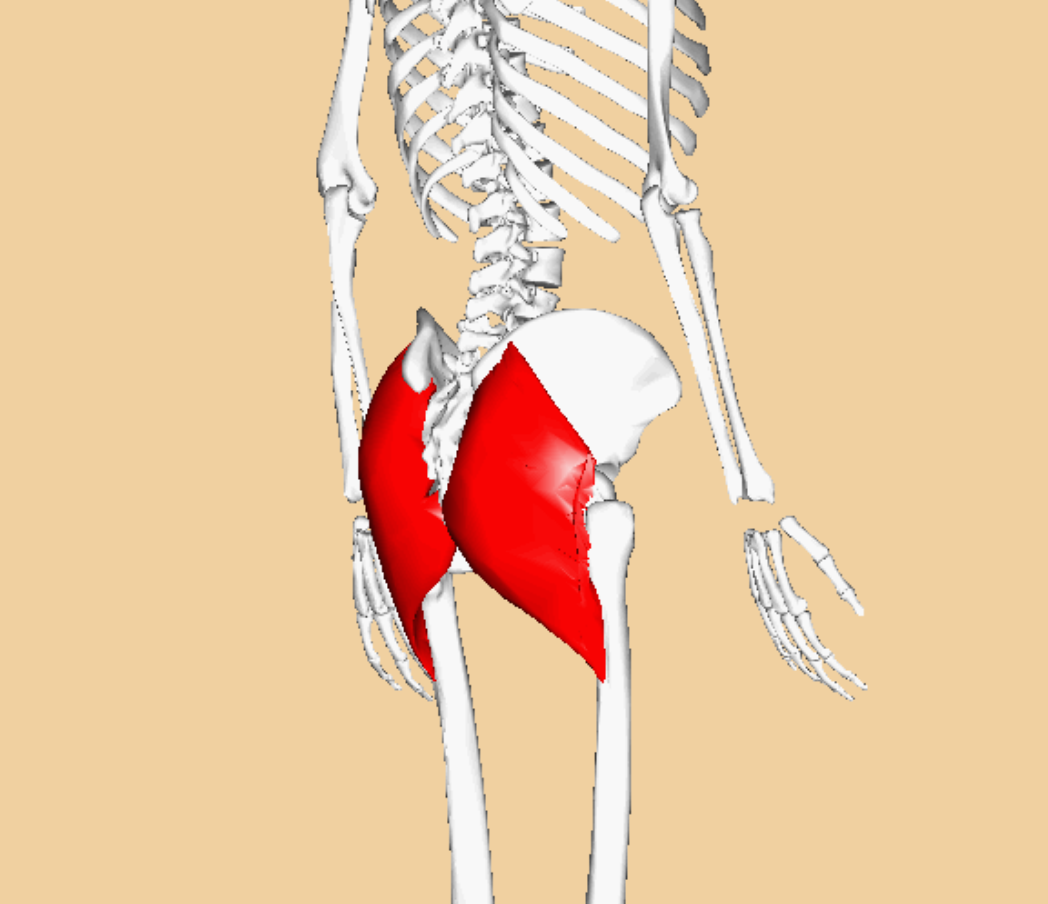

3. The eccentric role of the glutes in the lower extremity might be their most key contribution.

When heel strike happens, it kicks off the process of pronation in the lower extremity. This pronation drives internal rotation of the tibia and, in turn, the femur. There is a lot of ground reaction force and range of motion that must be controlled, so much of it is passed up the chain because we simply don’t have that much cross-sectional area in the muscles below the knee. Because it functions in three planes of motion, the gluteus maximus is in an awesome position to help by slowing down femoral internal rotation, adduction, and flexion.

If you’re looking to learn more about how functional anatomy impacts how you assess, coach, and program, I’d strongly encourage you to check out Mike Robertson’s new Complete Coach Certification. I’ve had the opportunity to review it, and it’s absolutely fantastic. You can learn more – and get a nice introductory discount – HERE.