5 Keys to Long-Term Deadlift Progress

In the fitness industry, for some reason, folks like to pigeonhole coaches into certain specialty roles. Over the years, I’ve been called the “mobility guy,” “the baseball guy,” and – most applicable to today’s article – “the deadlift guy.” You see, I really enjoy picking heavy things up off the ground, and I’ve gotten pretty good at doing so.

As a “deadlift guy” (whether I really identify with that label or not!), I’ve gotten a lot of inquiries over the years. These questions relate to programming, technique, exercise selection, and a host of even more obscure topics (such as: “why does my iPhone always auto-correct ‘deadlift’ to ‘deadliest;’ doesn’t anyone at Apple actually lift weights?”). In the process of answering loads of these questions and coaching thousands people on how to deadlift, I’ve picked up on some trends that explain why many people don’t make deadlift progress. Contrary to what you may assume, the deadlift is definitely a unique exercise that must be trained a bit differently than just about any other strength exercise. With that in mind, here are my top five keys for long-term deadlift progress.

1. Don’t have setbacks.

This could be said of all training goals, but the unfortunate truth is that a lot of people get hurt deadlifting. This might be because of poor deadlift technique or inappropriate programming, but regardless of the true cause, it goes without saying that it’s a big issue.

I learned this lesson early (age 21), as just a week after I pulled 400 for the first time, I felt a nice “pop” in my lower back during a warm-up set at 225. It set me back a good 3-4 months, but was a blessing in disguise, as it scared me into grooving better technique, as opposed to just piling more and more strength on top of a dysfunctional pattern. From there on out, I did a much better job of not only lifting with better technique, but also fluctuating my training stress within the strength training program and individual training sessions.

2. Recognize that your body may not be ready for specific deadlift variations.

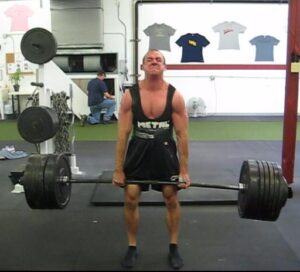

I’ve pulled 660 with a conventional stance, 630 sumo, and 700 on the trap bar. A big part of me being able to train all three lifts (and their variations) regularly was the fact that I’d built a good foundation of mobility and stability that enabled me to execute the lifts from a safe position. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case with everyone who deadlifts for the first time. In fact, for many general population folks, the conventional deadlift might never be an option purely from a risk: reward standpoint, as they simply can’t get into a safe starting position to start the lift. For that reason, we start all our athletes and clients with the trap bar, progress to sumo deadlifts, and see where things stand. Programming a conventional deadlift on Day 1 is like sending a 7th grader into a calculus class when he needs algebra first.

3. Train the deadlift frequently, but not necessarily with high volume.

It never ceases to amaze me how many lifters I encounter who say they want to improve the deadlift, yet answer “twice a month” when I ask them how often they train the lift! For some reason, many folks in the powerlifting world latched on the idea that if you just trained the squat or good morning, it’d automatically carry over to the deadlift. Sorry, that just isn’t the case – at least not if you want to make optimal progress.

I’d estimate that I’ve trained the deadlift twice a week for 80% of my training career, and once a week for the other 20%. It’s almost always trained after the squat within the training session. It may be lighter and for speed, or heavier for sets of 1-5 reps.

I can’t say that I’ve ever spent much time above six reps, though. I find that my percentages fall off quickly, and doing a lot of high rep work at 60% of my one-rep max doesn’t really do much for me besides give me a raging headache. Seriously, every time I pull heavy for high reps; my head pounds for a good day – and I really don’t feel like it gets me any closer to where I need to be.

Either train heavy or train to be fast off the floor, but don’t train to be slow, and methodical by conserving your energy for 87-rep sets.

4. Upper back, upper back, upper back!

Buying shirts and suit jackets is a royal pain in the butt, as my upper back is considerably larger than my arms. In fact, the size of my upper back is what inevitably forced me to go from the 165- to 181-pound weight class during my powerlifting days – in spite of the fact that I was trying to keep my weight down. I think it speaks volumes for how important upper back strength is for the deadlift, as my pulls were improving considerably faster than my squats over this time period. To give you a feel for how accidentally disproportionate deadlifting has made me over the years, take note of this recent picture. In looking at my traps, one would think that all I need to do is develop an underbite, and then I could have a prosperous career as a troll underneath a bridge, demanding tolls from unsuspecting passersby.

Very simply, having a strong upper back enables you to control the bar, as opposed to it controlling you. It’s obviously of great importance to getting the shoulder blades back at the top of the lift, but it’s also essential to making sure that the bar doesn’t drift away from you, which would effectively increase the distance between the weight and the axis of rotation (hips). Letting the bar drift away from you doesn’t just decrease the likelihood of you completing the lift; it also raises the stress on your spine, increasing your likelihood of injury. Having a strong upper back helps to spare your lower back.

You’ll find the best carryover from rowing variations, farmer’s walks, and rack pulls. However, vertical pulling variations (chin-ups, etc) can still have a beneficial effect. I also always responded well to doing heavy single-leg work, as it challenged my grip and upper back while I was still training the lower half.

5. Have a plan.

It’s easy to build a solid deadlift, but taking a “decent” amount of success and expecting it to automatically translate to really big time deadlift numbers is a recipe for disaster, as what you do to get to a 315 deadlift is going to be dramatically different from what you do to try to pull 500. Very simply, you need a plan.

To that end, if you’re looking for a good deadlift development program, I’d encourage you to check out The Specialization Success Guide. Whether you want to pack some poundage on your deadlift or just pick up some heavy stuff to look, feel, and move better, this is a great resource that I’d encourage you to check out.