The Truth About Shoulder Impingement: Part 2

In Part I, I went into some detail on why I really didn’t like the catch-all term “shoulder impingement.” This week, I’m going to talk about the different kinds of shoulder impingement: external and internal.

External impingement, also known as outlet impingement, is the one we hear about the most. Here, we’re dealing with compression of the rotator cuff – usually the supraspinatus, and over time, the infraspinatus (and biceps tendon) – by the undersurface of the acromion. This impingement can lead to bursal-sided rotator cuff tears – and happens a lot more with ordinary weekend warriors and very common in lifters (not to mention much more prevalent in older populations.

External impingement can be further subdivided into primary and secondary classifications. In primary impingement, the cause is related to the acromion – either due to bone spurring or congenital shape. As you can see in the photo below, hook (II) and beak (III) are worst than flat (I), as there are marked difference in “clearance” under the acromion.

Secondary impingement, on the other hand, is usually related to poor scapular stability (related to both tightness and weakness, as described in last week’s newsletter), which alters the position of the scapula. In both cases, pain is at the front and/or side of the shoulder and is irritated with overhead activity, scapular protraction, and several other activities (depending on the severity of the tissue problems). You’ll also generally see a lack of external rotation range-of-motion, as these are folks who do too much bench pressing and computer work (both of which shorten the internal rotators).

Conversely, internal impingement, also known as posterosuperior impingement, really wasn’t proposed until the early 1990s. This form of impingement is more common in younger individuals who are involved in overhead sports, making it more of an “athletic impingement.” Adaptive shortening and scarring of the posterior rotator cuff in these athletes causes a loss of internal rotation and an upward translation of the humeral head during the late cocking phase of throwing (or swimming): external rotation and abduction. These issues are magnified by poor scapular control, insufficient thoracic rotation, and weakness of the rotator cuff.

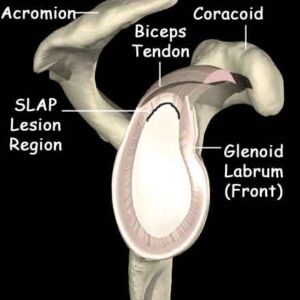

When the humeral head translates superiorly excessively in this position, it impinges on the posterior labrum and glenoid (socket), irritating the rotator cuff and biceps tendon along the way. So, pain usually starts in the back of the shoulder, as you are seeing irritation of the posterior fibers of the supraspinatus and anterior fibers of the infraspinatus tendons. Gradually, this pain may “shift” toward the front as the biceps tendon, and that implies labral involvement. At least initially, the pain is purely mechanical in nature; it won’t bother an athlete unless the “apprehension” position (full external rotation at 90 degrees of abduction) is created.

We often hear about SLAP lesions in the news. This refers to a superior labrum, anterior-posterior injury. In reality, when we are talking about labral injuries in overhead athletes as they relate to internal impingement, it’s mostly just posterior (although serious cases can eventually affect the anterior labrum, too). There are different kinds of SLAP lesions (1-4). Every baseball pitcher you’ll meet has a SLAP 1, which is just fraying. SLAP 2 lesions are far more serious and often require surgical intervention. SLAP 1 issues become SLAP 2 lesions when poor mobility and dynamic stability aren’t established.

So, just to bring you up to speed, we’ve got two different kinds of impingement, one of which (external) has two subcategories that mandate different treatment strategies (primary = surgery, secondary = corrective exercise). We also have two separate areas where pain presents (external = front/side, internal = back). That’s just the tip of the iceberg, though, as we have two more considerations…

First, symptomatic internal impingement tends to be “mechanical pain.” Unless you’re dealing with a more advanced case, athletes with symptomatic internal impingement only have pain when they get into the late cocking phase (and sometimes follow-through). It usually isn’t present when they’re just sitting around – and for this reason, they can usually be more aggressive in the weight room with upper body training. Keep in mind that I use the term “symptomatic” because I think that internal impingement is a physiological norm, just like I observed last week with external impingement. You’re essentially just going to go out of your way to avoid this “apprehension” position in the weight room by omitting exercises like back squats. An apprehension test – illustrated in the most enthusiastic video in internet history – is a quick and easy assessment many doctors and rehabilitation specialists use to check for symptomatic internal impingement, as it reproduces the injury mechanism.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, you are dealing with two rotator cuff tears that are fundamentally different. It’s these differences that make me think doctors need to get rid of the term “impingement.” Here’s the scoop:

Let’s say that we have two guys with partial thickness tears of the supraspinatus – one from external impingement and one from internal impingement.

With external impingement, we’re usually dealing with a bursal-sided tear, as the rubbing comes from the top (acromion). These issues will generally heal more quickly because the bursa actually has a decent blood supply.

With internal impingement, on the other hand, we’ve got an articular-sided tear, meaning that the wear on the tendon comes from underneath (glenoid). The tear is more interstitial in nature. Blood supply isn’t quite as good in this area, so healing is slower (or non-existent).

Traditionally, articular has been an athletic injury, and bursal has been a general population issue. This is not always the case, though.

Factor in the activity demands of overhead throwers, and they have more challenging tears and greater functional demands. Fortunately, they also typically have age and tissue quality on their sides, so things tend to even out.

With all these factors in mind, if a doctor ever tells you that you have “shoulder impingement,” ask:

1. Internal or external?

2. If external, is it primary or secondary? (It’ll probably be both)

3. If internal, is there labral involvement? Biceps tendon?

4. If internal, what is the internal rotation deficit? (They should measure it, as this will begin to dictate the rehabilitation plan)

5. Given my age, activity level, and the nature of the tear, do you feel that surgical or conservative treatment is best?

Click here to purchase the most comprehensive shoulder resource available today: Sturdy Shoulder Solutions.