Training Programs: Are Health and Aesthetics Mutually Exclusive?

Roughly once a week, I run Q&A sessions on my Facebook page. Often, they give rise to good blog ideas – and today’s post is a perfect example, as I received this inquiry during this week’s Q&A:

“How do you think that we, as fitness professionals, can help people move from looks-based result mentality to health-based result mentality?“

This post really got me thinking, as it can definitely be viewed in a number of different ways.

On one hand, I “get” what this fitness professional is trying to say: there are still a lot of people out there who are steadfastly adhering to old-school “body part splits” for training when it likely isn’t the most efficient way to get to their goals. We want training that improves quality of movement if we’re going to stay healthy and highly functional as the years go on.

On the other hand, I don’t think there is anything inherently wrong with folks wanting to look better – and allowing it to dictate their training approach as the “carrot at the end of the stick.” Whether we like it or not, what one sees in the mirror does have a dramatic impact on one’s health – psychological health, that is.

In order words, the question seems to imply that looking good and being healthy are mutually exclusive training goals. I simply don’t think that’s the case – and for a number of reasons.

First, “health” means something entirely different to everyone. We obviously have a ton of different measures of health status with respect to chronic diseases, but what about being “healthy” enough to take on life’s adventures on a daily basis? I know some powerlifters who would feel incredibly “unhealthy” if they tried to play racquetball, but I can guarantee you that if you took a racquetball only guy and asked him to train with a powerlifter for two hours, he’d feel really “unhealthy” the next day, too. If you train to be “healthy” in everything you do, you just might wind up not being really good at any one thing.

Second, I’d argue that there are loads of people out there who train exclusively for aesthetics and are incredibly healthy. Natural bodybuilders come to mind, and I know of a lot of people who “recreationally” bodybuild and supplement this training with powerlifting, Olympic lifting, sprint work, and recreational sports for variety and supplemental conditioning. I’m sure there are loads of accomplished “recreational” Crossfitters out there who have perfect blood work and no joint pain to match their developed physiques, too.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, it’s not our job to tell people what their goals should be; it’s our job to help them work toward them, even if it does conflict with our own personal biases.

However, I don’t think personal biases should be a problem in this context, though. You see, if you really look at successful strength and conditioning programs, they all have a ton of things in common. In fact, it might be 90% of the program that’s comparable across “disciplines.”

Everybody can foam roll and do mobility warm-ups, regardless of whether they want to look or just feel good.

Compound lower body exercise can benefit anyone, whether they want a firmer backside, better athletic performance, or just to fit in their jeans a little easier.

Most folks need extra horizontal pulling (rowing), regardless of whether they want to step on a bodybuilding stage or just not wind up with shoulder pain from slouching over the keyboard every day.

Fluctuating training stress and incorporating deloading periods is important whether you want to recovery and develop bigger biceps, or you just want to make sure you have enough energy left over after training to play with your kids at the end of the day.

I could go on and on, but the key message is that we can have both health and aesthetics – and if aesthetics are a goal that helps folks to work toward that end, then so be it. I’d be lying if I said that I don’t derive more motivation from seeing my abs in the mirror in the morning than I do from a report that my blood lipid panel looks good. It’s human nature that we’re more concerned with what is public (our appearance) than what is private (our health), so we might as well get used to it. Health goals are awesome, and accomplishments on this front should be celebrated, but don’t think you’re ever going to see a population shift toward wanting the “fit look” less than the “healthy feel.”

Taking it a step further, though, I think improved performance can be lumped in with aesthetics and health as a result of an effective training program. Successful programs might be 75% the same, but it’s tinkering with the other 25% that delivers the benefits on all three fronts.

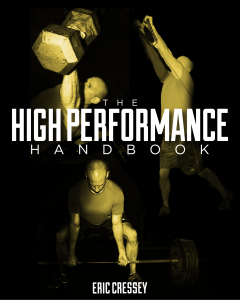

As an example, with The High Performance Handbook, my goal was to create a versatile “main” strength training program that initially could be easily modified based on posture, joint laxity, ideal training frequency, and supplemental conditioning. On the supplemental conditioning front, folks pick different options to shift the program to athletic performance, fat loss, strength improvement, or mass gain perspectives. Thereafter, individuals can choose from a number of different “special populations” modifications, whether it’s for folks who want more direct arm work, those who play overhead throwing sports, or those over the age of 50. Then, there are the obvious nutrition individualization components.

The point is that the best programs are the versatile ones that give people the wiggle room to pursue the goals – aesthetics, health, performance, or some combination of the three – that they hold dear.