The Most Important Three Words in Strength and Conditioning

From 2007 to 2009, I was a big sleeper stretch guy. All our throwing athletes did this stretch at the end of their training sessions, and we meticulously coached the technique to make sure it accomplished what we *hoped* it would accomplish. I featured it in the program in my first book, Maximum Strength, and this picture of me even shows up in the first row of photos on Google Images if you search for “sleeper stretch.”

Then, in March 2010, I attended my first Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) event and “saw the light.” I left the course with some great new positional breathing drills that often delivered quick results in terms of improving shoulder internal rotation – without having to actually stretch the shoulder, a joint that doesn’t really like to be stretched. Looking back, we were probably trying to “stretch” out an alignment issue – and that never ends well.

We’ve since progressed our approach, complementing PRI exercises with thoracic spine mobility drills and manual therapy at the shoulder in those who present with true internal rotation deficits. Only after they’ve still come up short following these initiatives do we actually encourage stretching of the glenohumeral (ball and socket) joint. And, even when that happens, it’s gentle side-lying cross-body stretching with the scapula stabilized; this has proven safer and more beneficial for improving internal rotation.

The three preceding paragraphs about my experiences with the sleeper stretch could really be summed up in three words:

I was wrong.

It’s not the only time I’ve been wrong, either.

I wish I’d done more barefoot work and ankle mobility training with the basketball players with whom I worked early in my career.

I wish I’d not just assumed that all athletes needed more thoracic mobility when, in fact, there are quite a few who have hypermobile t-spines.

I wish I’d focused more on the benefits of correct breathing – especially full exhalation – with athletes sooner in my career.

In my own powerlifting career, I wish I’d spent more time free squatting and less time box squatting. And, I wish I’d competed “raw” instead of with powerlifting equipment.

I’ve made some errors in the ways I evaluated, trained, and programmed for athletes. I’ve made dumb decisions in both my business and personal life. However, at the end of the day, I can attribute a lot of my improvements as a person and a professional to the fact that I was completely comfortable admitting, “I was wrong.” Heck, I’m so comfortable recognizing my mistakes that I’ve written entire posts on the subject!

This is trait just about every successful strength and conditioning coach generally shares. Humility is an essential trait for personal and professional advancement, especially in a dynamic field like strength and conditioning where new research and training techniques emerge on a daily basis.

This isn’t just limited to strength and conditioning, though. If you asks a lot of the best surgeons in the country, they’d admit that they were wrong in doing a lot of lateral release (knee) surgeries and thermal capsule (shoulder) shrinkage procedures earlier in their careers. And, they’d probably admit that they misdiagnosed a lot of cases of thoracic outlet syndrome as ulnar neuropathy. If they aren’t willing to admit their past mistakes, you probably ought to find a different doctor.

If you’re an athlete, the same can be said of seeking out a strength and conditioning coach. If the person writing your programs hasn’t learned from his/her mistakes, are you really getting a “modern” or forward-thinking program that has been tested in the trenches? We’ve all seen those programs – both in training and rehabilitation – that have been photocopied so many times over the years that they’re barely legible.

Likewise, if you’re an up-and-coming strength and conditioning coach, you want to seek out mentors that’ll admit their past mistakes and reflect on how they learned from them. Only then can they help you avoid making them, too. You’re better off learning under someone who has 15 years of strength and conditioning experience than someone who has 15 years of the same year of experience.

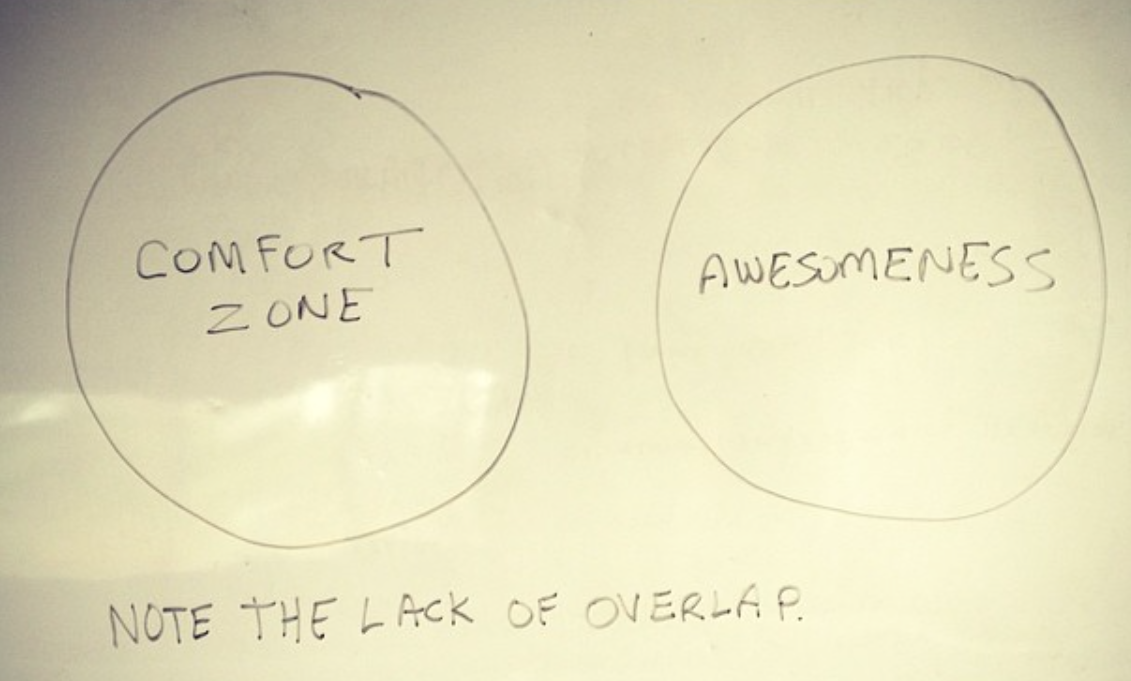

Finally, if you’re an established professional, the only way to grow is to get outside your comfort zone. Five years from now, if you’re not looking back on your current approaches and wondering what the heck you were thinking, then you’re stuck in the bubble on the left.

You need to visit other facilities, talk with other coaches, and empower your employees/co-workers with a voice that challenges the norm. I learn a lot from my staff on a daily basis. And, looking back on that first PRI event I attended, I was the only “non-clinician” in the room. I was surrounded by PTs, PTAs, respiratory therapists, pelvic floor therapists, and ATCs. I got out of my element and it changed the course of my career dramatically.

Looking back on these experiences when I was clearly wrong, part of me wants to send individual apology notes to all the athletes I saw early in my career. By that same token, though, I feel like thank you notes might be more appropriate, as these mistakes played an essential role in my growth as a coach and person.

If you’re looking for an up-to-date look on how we manage shoulders – including a look at identifying and addressing internal rotation deficits – be sure to check out my popular resource, Sturdy Shoulder Solutions.