Random Thoughts on Sports Performance Training – Installment 14

It’s time for the next installment of this popular series here at EricCressey.com, but I’ve pulled in some help from an old friend for this one. Given that his new DVD set, Elite Athletic Development 2.0, was just released this week, the one-and-only Mike Robertson agreed to chime in with some sports performance tips this week. Those beginning with “MR” are from Mike, and the ones with “EC” are me. Enjoy!

1. MR: When working with overhead athletes, learn to love specialty bars.

When it comes to athletes in general, it’s obvious that they are not powerlifters. Is it helpful if they’re strong? Absolutely. But let’s be honest – no one cares about how they get strong. You don’t get bonus points for deadlifting from the floor, nor do you necessarily have any reason to put a barbell on your back. At IFAST, we’re huge fans of specialty bars for our athletes, but especially for our baseball players.

Trap bars are kind of a god-send, if you ask me. It’s an incredibly easy exercise to coach, you reduce the mobility demands (vs. a sumo or conventional deadlift), and you can load a guy up fairly quickly without compromising technique.

On the other hand, just because we don’t put a barbell on our back doesn’t mean we don’t squat! The safety squat bar is an invaluable tool if you train baseball players (or really, any overhead athlete). You know that your wrist, elbow and shoulder are your money makers, so the last thing you want to do is expose yourself to injury in those areas. The safety squat bar front squat is awesome for newbies, as it teaches them a front squat pattern without having to “rack” the bar using the wrists, elbows and shoulders. I’ll often start my baseball players off with this variation for a month or two, just to get them back in the swing of things. If we want to load up the squat pattern a bit more, all we have to do is flip the safety bar around and now we’ve got a back squat progression that again unloads the upper extremity. Quite simply, if you train overhead athletes – or any athletes, for that matter – invest in a high quality trap and safety squat bar. You’ll thank me later.

2. EC: Show some love to the broad jump!

For some reason, in the world of athletic performance assessments, vertical jump testing gets all the attention. In my anecdotal experience, though, broad jump proficiency has a far greater carryover to actual athletic success. Bret Contreras has also alluded to this as part of his rationale for including hip thrusts and other loaded glute bridge variations in strength training programs; horizontal (as opposed to just vertical) force production really matters in sports.

That said, one reason some coaches shy away from programming broad jump variations in training programs is that they be a bit hard on the joints and elicit more soreness in the days that follow a training session. This is easily remedied by having an athlete land on a more forgiving surface (such as grass), or by using band-resisted broad jumps.

3. MR: Appreciate that push-ups can actually improve rotator cuff function!

Push-ups are a critical component of our training programs, and for numerous reasons. You see, push-ups (versus a traditional bench press), allow for a high degree of serratus anterior development. And I’d argue that in the upper body, the serratus anterior is one of the most overlooked, yet incredibly important, muscles we have. Strengthening the serratus anterior does a host of good things for us, most notably upwardly rotating the scapula. However, what many people don’t understand is how it actually improves thoracic kyphosis.

This is a really loaded topic, so I’ll try to keep it brief. Back in the day we would look at most people and say they have an excessive thoracic kyphosis, but I’m not entirely sure that’s true. What I think we see (more often than not) is a flat thoracic spine, coupled with shoulders that are rolled forward due to an inability to expand a chest wall. (Thank you, Postural Restoration Institute). Here’s an example EC posted a while back of a flat thoracic spine in action:

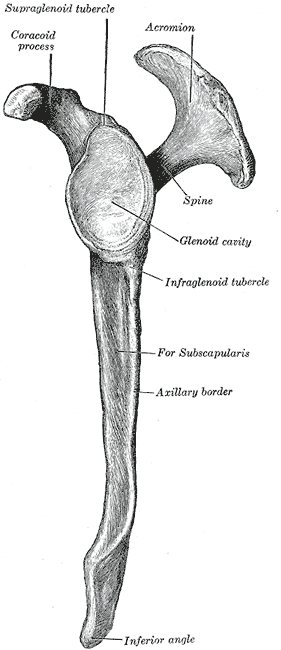

While we tend to get caught up on the scapular attachment site (or motion) of the serratus, it also attaches anteriorly to the ribcage. If we lock the scapulae in place and engage serratus anterior, it pulls on the rib cage and gives us a more normal thoracic kyphosis. Now I’m sure you may be thinking, why do we want a kyphosis? Isn’t more extension a good thing? You need a kyphosis (or subtle rounding of the upper back), because your scapulae are curved as well; just look at this side angle to appreciate it.

If you have a curved scapulae sitting on a flat upper back, you lose passive stability at the shoulder. And when we lose stability at the scapulae, we are virtually guaranteed to lose stability at the shoulder. Because the rotator cuff muscles attach to the scapula, trying to stabilize the glenohumeral (ball-and-socket) joint with a flat thoracic spine is like trying to shoot a cannon from a canoe.

Want more serratus? Incorporate more push-ups, and do them correctly. As EC notes in this video, don’t just let the arms do all the work; get the shoulder blades moving. The scapula should rotate toward the armpit as you press up and away from the floor:

Get this upper back positioning squared away, and you’ll improve rotator cuff control both transiently (positional stability) and chronically (better training results).

4. EC: Remember that joint range-of-motion falls off over the “athletic lifespan.”

It never ceases to amaze me how much a teenage athlete will change over the course of a year – even independent of training. If a kid goes through an 8-inch growth spurt at age 13, he’s usually going to go from that “loosey-goosey,” completely unstable presentation to the uncoordinated, stiff movement quality. Basically, the bones have stretched out quickly, and the soft tissue structures crossing the joints haven’t had time to catch up (let alone learn how to establish control of new stabilization demands).

What many folks fail to recognize is that “bad” stiffness doesn’t just increase in teenage athletes, but also in the decades that follow. It’s well established that joint laxity decreases over the lifespan; it’s one of several reasons why your 80-year-old grandmother isn’t as supremely mobile as she was in her 50s.

What’s the point? A lot of the foundational mobility drills you use with your teenage athletes are probably “keepers” that people can use over the course of their entire lifespan. So, teach them perfectly early on so as to not develop bad habits that will be magnified over decades.

5. MR: Remember that good hip development for athletes should be tri-planar.

Whether it’s stealing bases, returning a punt, or changing directions on the ice, there’s more to the hips than sagittal (straight ahead) plane development. Sure, it never hurts to be a stronger squatter or deadlifter, but I’d also argue that’s just the tip of the iceberg. We also need our athletes to be able to move well in both the frontal and transeverse planes as well. I like to think of the sagittal plane as the “key” that unlocks the frontal and transverse plane.

If you’re into the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) , you can even take this a step further and think of it like this: we need the ability to shift into and load our left hip, while we need the strength and stability to push (or get off) our right hip, particularly in those demonstrating this heavily asymmetric postural presentation.

Once we have that basic movement capacity, now we need to start cementing it. This can be done initially in the weight room, with exercises like dynamic chops, lifts, the TRX Rip Trainer, etc. I’m also a huge fan of concentric med ball throws as well. Start low to the hip initially, and then raise it up over time. Progress to eccentric as movement capacity and strength improve.

Taking this a step further, don’t be shy in doing some aggressive lateral plyo progressions as well. Work on Heidens/skier jumps with a stick first to develop eccentric strength and control, then work on improving speed, power and explosiveness. Last but not least, we need to prepare our athletes for the specific demands of their sport, and this is where lateral acceleration and crossover stepping comes into play. At the end of the day, use the weight room to get strong in the sagittal plane, but don’t forget that the frontal and transverse planes are critical for a highly-functioning athlete!

6. EC: Don’t be afraid to progress birddogs.

The birddog is an awesome core stability and hip mobility exercise, but it can quickly become really easy for athletes with some training experience under their belt. Not all exercises need to be progressed, but the band-resisted birddog is one way to add some variety and additional challenge for this invaluable exercise:

As I noted earlier, Mike and Joe Kenn recently released their Elite Athletic Development 2.0 Seminar DVD set. I’ve reviewed this product now myself, and it’s excellent. You can learn more HERE.