Tinkering vs. Overhauling – and the Problems with “Average”

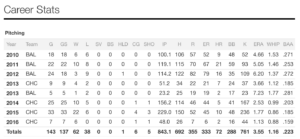

Over the past year or so, Cubs pitcher Jake Arrieta has been a highly celebrated MLB athlete not only for his dominant performances (including two no-hitters) on the mound, but also for “reincarnating” his career with a new organization. Previously, Arrieta had been a member of the Baltimore Orioles organization – and while he had been a Major League regular, his performance had been relatively unremarkable. That all changed when he arrived in Chicago.

Source: Yahoo Sports

In Tom Verducci’s recent piece for Sports Illustrated, Arrieta detailed that his struggles with the Orioles were heavily impacted by constant adjustments with everything from mechanics, to pitch selection, to where he stood on the rubber. He was even quoted as saying, “I pitched for years not being comfortable with anything I was doing. I was trying to be somebody else.”

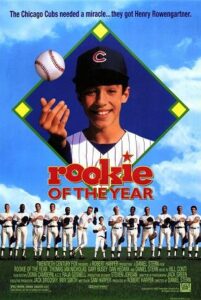

I’m always cautious to take everything I hear in the sports media with a grain of salt, and this blog is certainly not intended to be a criticism of anyone in the Orioles organization. However, what I can say is that this story isn’t unfamiliar in the world of Major League Baseball. There is a lot of overcoaching that goes on as many coaches try to fit pitchers and hitters into specific mechanic models. In other words, rather than looking for ways to make Jake Arrieta into the best Jake Arrieta possible, some coaches look to make athletes into Greg Maddux or Nolan Ryan – and they usually wind up with Henry Rowengartner (minus the arm speed).

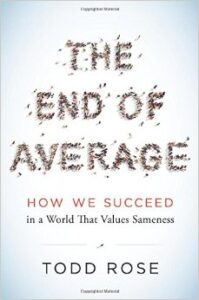

This “phenomenon” isn’t confined to baseball, however. In his outstanding book, The End of Average, Harvard professor Todd Rose, writes: “The real difficulty is not finding new ways to distinguish talent; it is getting rid of the one dimensional blinders that prevented us from seeing it all along.” Moreover, he adds, “We live in a world that demands we be the same as everyone else – only better – and reduces the American dream to a narrow yearning to be relatively better than the people around us rather than the best version of ourselves.”

As Rose notes, we can extend this concept to the idea of standardized testing for students and conventional hiring procedures for new employees, both of which often overlook the brilliant individuals among us who may be wildly capable of remarkable contributions if put in the right situations. In short, pushing the “average” rarely allows anyone to demonstrate – let alone leverage – their unique potential.

This is where coaching becomes more of an art than just a science. On the pitching side of things, we know there are certain positions all successful pitchers get to in their deliveries – and there are certainly bad positions they should probably avoid to stay healthy. With that said, we have to “reconcile” this knowledge with the realization that some of these “bad positions” may help pitchers generate greater velocity, influence pitch movement, or add deception. If we try to change them – especially at the highest level – we may take away exactly what makes a pitcher successful.

You can draw parallels in a lifting environment. Some of the best deadlifters of all time pull conventional, and others use a sumo stance. Their individual anthropometry, training histories, and success to date govern the decision of how to pick heavy things up off the ground.

It’s important to note, however, that it’s very easy to play Monday Morning Quarterback in situations like these, as hindsight is always 20/20. Long-time CSP athlete Corey Kluber won the American League Cy Young award in 2014 in large part because he switched to a 2-seam fastball with the help of Indians pitching coaches Ruben Niebla and Mickey Calloway. And, another long-time CSP athlete, Jeremy Hazelbaker, is one of the feel-good stories of Major League Baseball after a subtle adjustment to his swing from a Midwest hitting coach, Mike Shirley, yielded huge results and put him on the Cardinals opening day roster after seven years in the minor leagues.

Arrieta’s Cubs teammate Jason Hammel spent some time with us at Cressey Sports Performance this off-season and made some mechanical adjustments, and he is off to a good start with a 4-0 record and 1.85 ERA. The point is that we hear a lot more about failures than we do about success stories, and it’s really easy to rant when things don’t work out. Subtle adjustments that keep guys healthy and confident don’t always show up on the radar – and as a result, some really important and tactful coaches from all walks of life don’t always get the recognition they deserve.

So when is it right to tinker on the coaching side? And, are there commonalities among what we’d see in pitchers, lifters, and other facets of the performance world? Here are seven questions I think you need to ask to determine whether the time is right to make a change:

1. Has the athlete been injured using the approach?

If an athlete can’t stay healthy, a change might be imperative.

2. Has the athlete stagnated or been ineffective with the approach?

The more an athlete struggles doing it his way, the more open he’ll be to modifying an approach. Career minor leaguers will buy in a lot easier than big leaguers – and the minor leaguers definitely have much less to lose if things don’t work out. Conversely, Jason Hammel already had over eight years of MLB service time before I even met him; we weren’t about to drastically change things.

3. Is the athlete novice enough that a change is easy to acquire and implement?

It’s a lot easier to correct a 135-pound deadlift than it is to correct a 500-pound deadlift. You’re best of fixing faulty patterns before a lifter has years to accumulate volume of loading the dysfunction. This is one reason why I’d rather work with a young athlete before he has a chance to start lifting on his own; there aren’t any bad patterns to “undo.”

4. What’s the minimum effective dose that can be applied to “test the waters” of change?

Can a “tinker” be applied instead of an “overhaul?” Switching from a 4-seam fastball to a 2-seam fastball is a lot less aggressive than switching from a 4-seam fastball to a knuckleball. And, it’s probably easier to go from an ultra-wise sumo deadlift to a narrower sumo stance than it is to go all the way to a conventional set-up.

5. How can you involve the athlete in the decision-making process with respect to modifications?

The concept of cognitive dissonance tells us that people really don’t like conflict and generally like to avoid it. This works hand-in-hand with the concept of confirmation bias; we like to hear information that agrees with our beliefs and actions. In their fantastic book, Decisive, Chip and Dan Heath write, “In reviewing more than 91 studies of over 8,000 participants, the researchers concluded that we are more than twice as likely to favor confirming information than dis-confirming information.” Furthermore, the Heaths note, “The confirmation bias also increased when people had previously invested a lot of time or effort in a given issue.”

How, then, can we involve our athletes and clients in the decision-making process so that they effectively feel that the necessary changes are their ideas? And, can we regularly solicit feedback along the way to emphasize that it’s “their show?”

6. How can we change the situation rather than the person?

In Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard, another great read from the Heath brothers, the authors note that you will almost never effect quick change a person, but you can always work to change the situation that governs how a person acts. If a pitcher’s velocity isn’t very good in the first inning (particularly during colder times of year), there’s a good chance he needs to extend his warm-up. However, many pitchers are very rigid about messing with pre-game routines. Maybe you just encourage him to do more of it inside where it’s warmer, or have him wear a long-sleeve shirt until he starts sweating. Here, you’re impacting his surroundings far more than his beliefs.

7. Can the change be more efficiently implemented utilizing an athlete or client’s learning style?

All individuals have slightly different learning styles (one more reason “average”coaching isn’t optimal). Some athletes simply need to be told what to do. Others can just observe an exercise to learn it. Finally, there are those who need to actually be put in the right position to feel and exercise and learn it that way. And, you can even break these three categories down even further with more specific visual, auditory, and kinesthetic awareness coaching cues. The more we understand individual learning styles, the more we can streamline our coaching with clear and concise direction. If a adjustment is perceived easy to understand and implement, an athlete will be far more likely to “buy in.”

Closing Thoughts

On the whole, I think there is a lot of over-coaching going on in today’s sports. Above all else, I think us coaches need to talk less and listen more so that athletes can be athletic. And, when a change is warranted, we need to make sure it’s a tinker and not an overhaul – and it’s important to give an athlete or client and ownership stake in the process.