Random Thoughts on Sports Performance Training – Installment 19

It’s time for the June installment of “Random Thoughts on Sports Performance Training.” With the introductory sale on Functional Stability Training: Optimizing Movement ending on Sunday at midnight, I’m going to use this post as an opportunity to highlight one of the key concepts that resounds throughout the product: relative stiffness.

1. All successful coaching hinges on relative stiffness – whether you’re aware of it or not.

I first came across the concept of relative stiffness in reading Shirley Sahrmann’s work. This principle holds that the stiffness in one region (muscles/tendons, ligaments, or joint) has can have a functional impact on the compensatory motion at an adjacent joint that may have more or less stiffness. You’ll also hear it referred to as “regional interdependence” and the “joint-by-joint” approach by the FMS/SFMA and Mike Boyle, respectively.

For those who do best with examples, think of lower back pain in someone who has an immobile thoracic spine and hips. They don’t move through these regions (excessive stiffness), so the lumbar spine (insufficient stiffness) just compensate with excessive motion. Likewise, a female soccer player with insufficient “good stiffness” in the hip external rotators and hamstrings might be more likely to suffer an ACL injury, as this deficit allows excessive motion into knee valgus and hyperextension.

This is why a knowledge of functional anatomy is so key for strength and conditioning coaches. Every cue you use is an attempt to either increase or decrease stiffness. When you hear Dr. Stuart McGill say, “lock the ribs to the pelvis,” he’s encouraging more (anterior) core stiffness. When you hear “double chin,” it’s to increase stiffness of the deep neck flexors. When you ask an athlete to take the arms overhead during a mobility drill, you’re looking to decrease stiffness through the lats, thoracic spine, pec minor, etc. – and increase stiffness through the scapular upward rotators, anterior core, deep neck flexors, etc.

In short, absolutely everything we do in training and in life is impacted by this relative stiffness.

2. Remember that elbow hyperextension doesn’t only occur because of joint hypermobility.

I’ve written frequently about how elbow hyperextension at the top of push-ups is a big problem, especially in hypermobile athletes who may be more predisposed to the issue. Typically, this is simply a technique issue; you tell athletes to stop doing it, and they do.

However, this doesn’t mean that they’ll automatically correct the tendency on other movements – like catching a snatch overhead, or throwing a baseball. It’s when we look at the problem through a larger lens that we realize there is a big relationship to a lack of scapular motion. If you don’t have enough good stiffness in serratus anterior to get the scapula to “wrap” around the rib cage and upwardly rotate, you’ll have to go elsewhere to find this motion (elbow hypermobility). This is why I’m a huge stickler for getting good scapular movement on the rib cage – and the yoga push-up is a great way to train it. Think “more scap, less elbow.”

3. If you want job security, become a hip surgeon.

The other day, I was speaking with a good friend who works with a lot of strength competitors – powerlifting, Olympic lifting, and Crossfit – and he made a comment that really stood out to me: “I’m seeing uglier hips than ever – even with females.”

This has some pretty crazy clinical implications. Most females of “strength sport competitor age” have quite a bit of natural joint hypermobility, so they typically present with excellent hip range-of-motion prior to the age of 40. Even females who sit at computers all day rarely present with brutal hip ROM before they’re middle-aged. What does this tell us? We have a lot of females who are developing reactive changes (bony overgrowth = bad stiffness) in their hips well too early, and when they later add increased ligamentous stiffness and a greater tendency toward degenerative changes (both normal with aging), we are going to see some really bad clinical hip presentations.

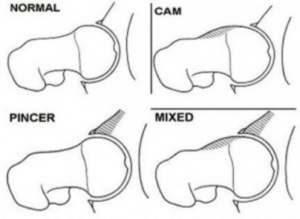

As an aside, it’s widely debated whether those with femoracetabular impingement (FAI) are born with it, or whether it becomes part of “normal” development in some individuals. World-renowned hip specialist Marc Phillipon put that debate to rest with a 2013 study that examined how the incidence of FAI changed across various stages of youth hockey. At the PeeWee (10-12 years old) level, 37% had FAI and 48% had labral tears. These numbers went to 63% and 63% at the Bantam level (ages 13-15), and 93% and 93% at the Midget (ages 16-19) levels, respectively. The longer one played hockey, the messier the hip – and the greater the likelihood that the FAI would “chew up” the labrum.

Source: Lavigne et al.: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15043094

So, whether it’s strength sport athletes, hockey players, or some other kind of athlete, if you want job security, become a hip surgeon – and expect to do a lot of hip replacements in 2040 and beyond. There’s a good chance these folks will need multiple replacements over the course of their life, too, if the longevity of the hardware doesn’t improve before then. The same can probably be said for shoulders, too.

How does it relate to relative stiffness? Once you’ve used up all the “bad” stiffness you can acquire – muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint – there’s a good chance that you’ll have beaten at least some structure up enough to warrant a surgery.

Wrap-up

I could go on and on with other examples of relative stiffness in action, but the truth is that they are countless – and that’s why it’s so important to appreciate this concept. To that end, I’d highly recommend you check out Mike Reinold and my new resource, Functional Stability Training: Optimizing Movement. It’s on sale at an introductory $30 off discount through this Sunday at midnight.