8 Training Tips for the New Dad

When I first started getting some noteworthy publications back in 2003, I was a green-around-the-gills 22-year-old graduate student. I had a decent foundation of knowledge in a very specific realm, but in reality, I knew very little about the real world.

In the years that followed, I learned a lot about a lot of things. I competed extensively in powerlifting, read and wrote a ton, and attended and spoke at loads of seminars. We opened Cressey Sports Performance in 2007, and went through three expansions – and trained athletes from all walks of life, including baseball players from all 30 Major League organizations.

In spite of all these experiences, it wasn’t until the fall of 2014 that I really learned about true responsibility. That September, my very pregnant wife and I moved to Jupiter, FL to open up our second Cressey Sports Performance location.

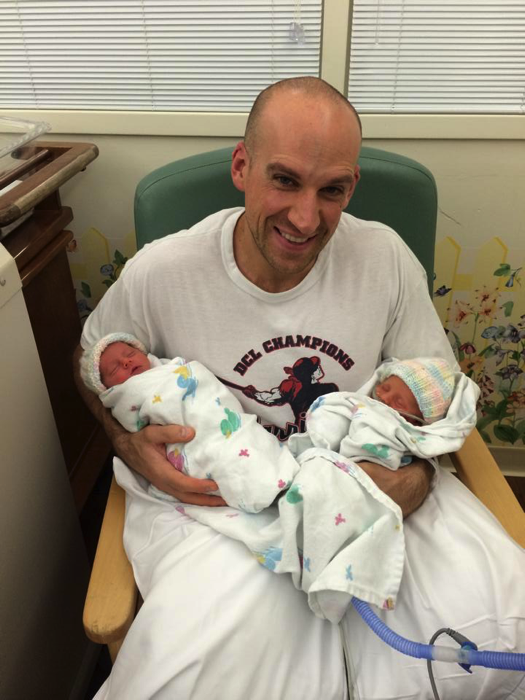

Three weeks after the new facility opened, amidst the chaos of moving to a new state and opening a new business, I awoke one morning at 5AM to my wife yelling, “Eric, my water broke!” Five hours later, we were proud parent of twin daughters – and I was in for more lessons than I’d learned in the previous 14 years of coursework, reading, seminars, training, and business.

It was at that point that I realized I’d never had any empathy for clients I’d trained who had kids at home. I’d always been selfish; I ate, slept, and trained whenever I wanted to do so – and I had assumed that they could always do the same. When you have kids, you back-burner your own needs for good.

As you can probably infer, having twins dominated me. For the first 12 weeks, I typically slept 8:30PM through midnight each night, with any other shut-eye during the day serving as bonus. The quality of my training suffered, and my nutrition slipped as my meal-prep time went by the wayside. I ate more protein bars on the fly, and consumed way too much caffeine to get through the days.

By the time the girls were six months old, I was down roughly ten pounds and a fair amount of strength in spite of the fact that I’d tried like crazy to not miss a beat with my training. It was far and away the most challenging six months of my life, but it was also remarkably rewarding on a number of fronts.

Our daughters are about 18 months old now, and the new facility is much more established – so things are a lot easier today. It’s given me some time to reflect on what I learned, and what I would have done differently in the way I took care of myself during that initial phase. Whether you’re a new father or planning/hoping to become one, I sincerely hope that you’ll take these strategies to heart.

1. Use caffeine to make up for sleep deprivation, but not for crappy diet.

Fatigue during exercise is an extremely complex topic, and we’re still somewhat unclear of all the mechanisms for it. By contrast, fatigue in your daily life is remarkably simple: outside of medical conditions that may cause it, you’re tired because you either a) aren’t sleeping enough or b) aren’t putting the right stuff in your body. The former is a normal part of parenting, but the latter doesn’t have to be.

The two biggest culprits we see with the athletes we encounter always seem to be dehydration and too many of the wrong carbs at the wrong times. If you aren’t drinking enough water, and you’re letting your blood sugar bounce all over the place, you’re going to get tired.

Having a few cups of coffee a day isn’t a problem; having 27 of them plus five energy drinks is. If your nutrition is reasonably good, you won’t have to go to this excess.

2. Clearly communicate a reasonable training schedule.

The old adage goes, “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” This is as true in training with a newborn at home as it is in almost any other part of your life.

I’ll be direct with you: if you try to find time, you’ll fail miserably. If you make time, you’ll do a lot better. However, that’s easier said than done, as there are a lot more competing demands for your attention when you have a baby at home.

This is where I was very fortunate: my wife is a gym rat herself. In fact, I had to hold her back from kicking down the door to the gym to train just 7-10 days after her C-section. To that end, we had some gym schedule reciprocity going; I’d watch the kids while she trained, and she’d watch them while I trained. Sometimes, when the girls were very young, we could bring them with us while we both trained. We also had a nanny who could help out to make sure that we had time when we needed it.

Regardless of how you approach it, it only works if you schedule it. Trust me on this one, as it will endure for a long-time.

3. Pare back on frequency.

Get the delusion of training six days a week out of your head right now. I tried to do it while sleeping 3-4 hours per night, and it went over like a fart in church. You can’t just keep adding when your recovery capacity is compromised.

For most people, three full-body lifts per week is a good bet. You might be able to get away with four if you aren’t doing much, if any, metabolic conditioning. If you have to pare back to two lifts per week in the short-term, you can certainly get away with that, too. Scenarios like this are one reason I offered 4x/week, 3x/week, and 2x/week training options in my High Performance Handbook; sometimes, life gets in the way and you need a strategy to prioritize certain portions of your training while eliminating other components.

The point is that you have to be realistic with your training goals. Maintenance is an acceptable goal in this situation, as much as it might be unchartered waters for you.

4. Fluctuate intensity and volume.

One lesson I’ve learned over the years that never ceases to amaze me is that the more experienced you are, the less frequently you need to lift to maintain your strength. It’s really hard to improve your strength, but surprisingly easy to maintain it. Even just taking a few heavy singles over 90% of your max each month seems to do the trick for most intermediate and advanced lifters.

This is an especially important “phenomenon” to remember during a period of sleep deprivation. “Fatigue masks fitness,” so the chances of you feeling good enough to push huge weights aren’t very high. You just have to do “enough.”

A good general guideline I would put out there is to always work high or low, but rarely in the middle. This has two meanings:

a. With your metabolic conditioning, either do high-intensity interval training, or stick to low-key aerobic work to help with recovery. Spending a lot of time doing work at 80% of your max heart rate is like trying to ride two horses with one saddle (check out my old article, Cardio Confusion, for details on why).

b. You need to cycle sessions of higher intensity or volume in to your training program to maintain a training effect. I think a good rule of thumb at this time frame in your life is to hit the higher intensity portion once a month and higher volume once a month. The other two weeks would be lower key in a format like this:

Week 1: lower intensity and volume

Week 2: higher intensity, lower volume

Week 3: lower intensity and volume

Week 4: higher volume, lower intensity

Note: for more information on deloading strategies, check out my e-book, The Art of the Deload.

5. Condition at home.

This is one way in which you might be able to slightly up the training frequency without adding a ton of stress. If you can score a quick 20-30 minute conditioning session at home (or sprinting at a park nearby), it can definitely go a long way. I use my rowing machine at home once a week year-round. Additionally, if you’re really badass, you can throw on a 100-pound weight-vest while pushing the double stroller and walking the dog.

6. Outsource wherever possible, and welcome help.

I often tell our athletes that “stress is stress.” At the end of the day, your body doesn’t really care whether you have a big project due at work or you’re trying to squat 405 for 10 reps; both are stressful to your system.

Having a kid shifts a big chunk of your “stress allotment” to outside the gym. And, it pushes out a lot of the important stress management approaches – sleep, quality nutrition, massage – that you might normally employ to manage the stress the body encounters.

With that in mind, it’s to your advantage to deflect some of this stress here and there. I’m not encouraging you to have a nanny raise your kid for you; I’m simply saying that it’s okay to ask for help. Nobody is going to judge you as a bad parent if a babysitter or family member watches your kid for a few hours while you get a lift in. And, if you have the financial resources, outsourcing food preparation can ensure that you’ve got healthy nutrition options at your fingertips. My mother-in-law lived with us for six weeks after our daughters were born, and it was a game-changer for us.

Just as Bill Gates doesn’t waste his precious time mowing his own lawn, you shouldn’t try to handle absolutely everything. It’s okay to ask for help.

7. Embrace simplicity – and do the simple things savagely well.

In my early days as a father, I had a habit of trying to take complex solutions to simple problems. The babies would cry, so I’d try to change the setting on their swing, turn on some music, give them an elaborate toy, or make a bunch of silly faces. Usually, the solution was just to feed them, change a diaper, or simply hold them.

A simple approach has merit for your training – especially during this crazy time of your life. When you have a newborn at home, it’s not the time for an elaborate squat specialization program, loads of direct arm work, or a 45-minute feel-good foam rolling session. Stick to the meat and potatoes: squats, deadlifts, presses, rows, lunges, chin-ups, etc.

I’d even argue that if you were ever going to embark on a one-set-to-failure machine based training block, this would be the time to do it. There’s quick adjustments on most selectorized equipment and the prospects of doing 6-8 sets in a training session will sound pretty appealing with you are working on three hours sleep and only have 30 minutes to get a training session in. Simplicity works.

It also works on the nutrition front. Make sure drink plenty of water and eat protein and veggies at every meal. Nobody is going to judge you if you have eggs for dinner because you didn’t have time to prepare something elaborate.

8. Remember that someone always has it harder than you do.

Strategies are all well and good, but perspective is invaluable.

Very simply, your significant other has it as lot worse than you. Pregnancy and childbirth are tremendously hard on women.

First, a lot of women deal with nausea (“morning sickness”) early in pregnancy. Constantly wanting to vomit isn’t exactly good for consistent, high-quality training. The truth is that this is the tip of the iceberg, though; they may experience heartburn, constipation, or any of the other fun symptoms elevated progesterone can deliver.

Second, as the baby grows during pregnancy, the woman’s center of mass is displaced forward relative to the base of support. This effectively rewires a long-term, engrained pattern of stabilization – and explains why many pregnant women wind up with back pain.

Third, remember that the baby grows under the rectus abdominus. So, the muscles of the anterior core are heavily overstretched and in a tough position to provide much support. I can remember when my wife – who can normally bang out 10-12 chin-ups – tried to do one when she was about six months pregnant. She did a half a rep, told me that it didn’t feel good at all – and she didn’t attempt another one for the rest of her pregnancy. Just putting the arms overhead can really stretch and already-lengthened anterior core significantly.

Fourth, during pregnancy, concentrations of the hormone relaxin increase dramatically to prepare the “lower quarters” for the stretching that takes place during childbirth. This hormone also works on ligaments at other joints, so women – who are normally more loose-jointed than man, anyway – become even more hypermobile. Less passive stability – combined with the anterior weight shift and lengthened core musculature – is a recipe for pain.

Just when you think things can’t get any physically harder for women, though, they have to go through the trauma of childbirth – or have a hole cut in their abdomen for a C-section. And, instead of the rehabilitation they deserve at this point, they get to start breastfeeding – and encountering sleep deprivation that’s far worse than yours.

Sorry, dude; someone has it rougher than you.