The Biggest Mistake in Program Design

Today’s guest post comes from former Cressey Sports Performance intern and current Boston Bruins Head Performance Coach Kevin Neeld. It’s timely, as he’s a co-creator of the new Optimizing Adaptation and Performance resource that was just released. I’ve reviewed it and it’s outstanding; definitely check it out HERE, as there’s a $50 off introductory discount in place this week. -EC

My programs look at a lot different now than they did ten years ago. This is true despite my “big rock” principals and general exercise progression-regression strategies changing very little.

The evolution of my programs has come largely from acknowledging my own biases, recognizing parallel paths to the same training adaptation, and generally trying to avoid the major program design mistake of training the sport, not the athlete.

[bctt tweet=”All athletes competing in the same sport do not have the same needs.”]

This may seem like a simple statement, but the overwhelming majority of training programs are designed based on the demands of a sport, and not the specific needs of the athlete.

More Than Just Exercise Selection

My first exposure to this concept came early in my career when athletes showed up with a unique injury histories that required finding substitutions for exercises that provoked past injury symptoms.

This is certainly a step in the right direction, but effective program design involves a lot more than just picking exercises that won’t hurt.

Simply, exercise selection does not determine the physiological adaptation; loading parameters do.

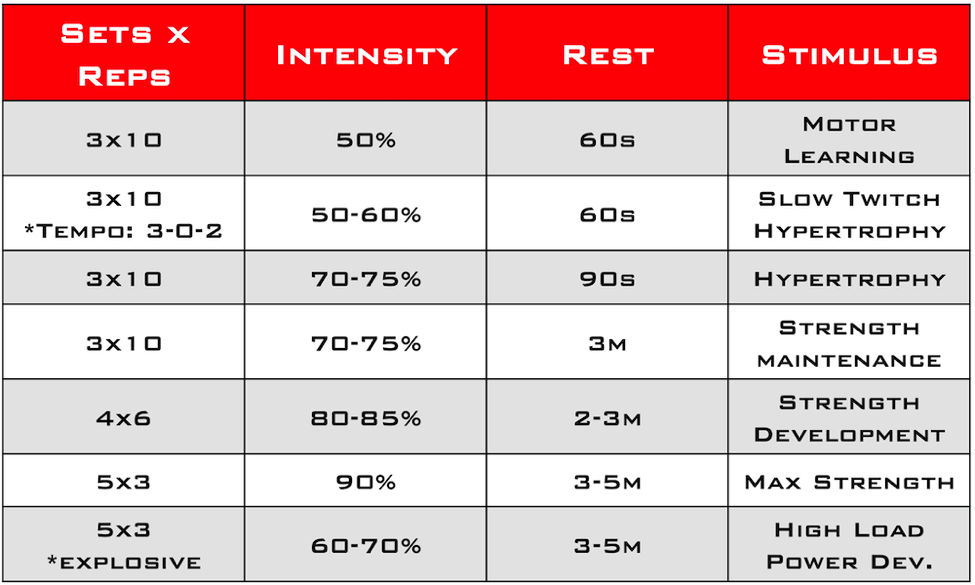

The table below displays several common loading parameters, and the adaptation stimulus each creates within the athlete.

The same exercise can be used to groove a specific movement pattern, develop muscle size, increase maximum strength, and improve power.

Using movement-based assessments in conjunction with injury history to find exercises the athlete can perform correctly and safely is an important foundational step, but it won’t dictate the athlete’s training outcome.

Acknowledge Individual Goals

Each athlete trains for a different reason.

Some want to get bigger and stronger. Most want to get faster. Some simply want to be healthy (i.e. durable).

A general program with well-thought out phase progressions may lead to improvements in each of these areas, particularly in young and untrained athletes.

However, a general program is unlikely to optimize the development of the qualities the athlete is most interested in improving.

Several years ago, I started asking myself a simple question: “How would my approach change if my entire career depended on the success of this one athlete?”

Prior to wrestling with this question, I had overlooked opportunities to further individualize training programs because I over-emphasized logistical constraints to athletes following different programs within the same group, and frankly, I didn’t realize the results the athletes were getting weren’t as significant as they could be.

Consider two athletes that both have a 12-week off-season. One has a goal of putting on size and strength, and the other just wants to get faster. Will the same program lead to optimal improvements in both areas?

Unlikely.

Fixating on the Destination, Ignoring the Starting Line

Every time I’ve added a new assessment or test to my intake process, I’ve learned something.

For example, early on I thought all that was required to get an athlete to perform an exercise well was good coaching and a little practice.

When I first started implementing movement assessments, it became immediately apparent that athletes had wildly different structures and movement capacities, and that certain athletes simply could not get into optimal positions to perform specific exercises correctly.

Of course, unique characteristics don’t only apply to movement capacity, but to all physical qualities. This became really apparent when I started analyzing team/group test results using aggregate scores.

Aggregate scores combine performance in different tests of the same quality to create a score for that quality. For example, if a testing protocol involves 3-RMs in three different exercises (e.g. Trap Bar Deadlift, Pull-Up, and Bench Press), performance on the three tests could be combined to create a single “Strength” score.

With an appropriately comprehensive testing battery, these aggregate scores provide a very simple and effective tool for identifying the athlete’s performance profile, and communicating areas of need to the athlete.

The graph below presents four different athlete profiles. From left to the right, each column represents performance in Movement Capacity, Speed, Power, Upper Body Strength, Anaerobic Conditioning, and Aerobic Conditioning.

Red and green bars represent position averages and best performances, respectively.

Should these athletes follow the same program?

This process is extremely important for two reasons.

First, the athlete may not be communicating the most optimal training goal.

Athletes express training goals for different reasons. Ideally, the goal would be based on identifying a limiting factor that is preventing the athlete from earning an opportunity to compete at their desired level.

But frequently training goals are arrived at much more arbitrarily. For example, an athlete may want to get bigger and stronger because they have a friend (or older sibling) that is stronger.

Or they say they want to get faster…because that’s what everyone says, even if it’s not their most pressing need.

A comprehensive testing process can help illustrate the athlete’s strengths and weaknesses so decisions about the best training target can be discussed with better context.

Second, the athlete may not possess the fundamental physical capacity to make optimal progress in their desired training goal.

This comes back to a very straight-forward idea: even if the destination is the same, the starting point is not.

In the most simplistic terms, expressing speed requires creating high amounts of force, quickly, in efficient movement patterns.

If an athlete wants to improve speed, but lacks sufficient strength, creating a program that emphasizes improvements in the athlete’s ability to produce force will be the most effective “speed training” program for that athlete.

Alternatively, an athlete with above average speed but severely limited movement capacity may have the right “engine” to be fast, but can’t get into the optimal positions to express that engine’s capacity within efficient sport movements.

As a third example, another athlete may have above average strength and appropriate movement capacity, but simply can’t apply force quickly. This athlete will benefit from a program that emphasizes speed, power, and rate of force development.

Finally, an athlete may simply be under-trained and benefit from a more general program that addresses multiple qualities of need.

This may seem like a hypothetical scenario, but these are the exact cases presented in the graphs above.

Top Left: Lacks sufficient strength.

Bottom Left: Lacks sufficient movement capacity.

Top Right: Lacks speed/power

Bottom Right: Under-trained

Wrap Up

Optimizing an athlete’s training progress requires having an individualized target, and an in-depth understanding of the athlete’s current capabilities. It’s only with a clear vision of both the starting point, and destination that the most effective path can be determined.

The biggest change to my training programs came when I stopped thinking about how I could design the perfect program, and started asking how I could design the best program for a specific athlete to achieve a specific goal.

I’ll leave you with the question that still guides my program design decisions today: “How would your approach change if your entire career depended on the success of this one athlete?”

To learn more about Optimizing Adaptation and Performance from Kevin, Mike Potenza (San Jose Sharks), and James LaValle (authority in nutrition and supplementation), head HERE. It’s on sale for $50 off as an introductory discount, and I’d highly encourage you to give it a watch.