A Coach’s View on Internal vs. External Cueing

Today’s guest post comes from Matt Kuzdub.

Stay on top of the ball. Extend the arms. Stay tall. Finish high. Stay back. Follow-through. Use your legs. Snap your wrist…

You’ve probably heard these cues before. Maybe you’ve even used them yourself. From individual sports like tennis, to team sports like baseball, and even in the weight room, coaches have been using verbal cues like these for decades.

While some may be effective, many have issues. For instance, if I tell an athlete, “use more of your legs” when trying to jump higher, what does that really mean?

You see, most of these cues are a bit vague and leave room for ambiguity. But the root problem is this: the types of cues we give an athlete will direct their focus and attention. And this, in turn, will impact their ability to change a movement and learn a new skill.

So the question becomes: what should coaches bring their athletes’ attention to during practices and drills? The same question can be asked about the gym; does cueing differ on the field vs in the gym? Surely learning to hit a 95mph fastball with the game on the line isn’t the same as setting a bench press PR in the weight room.

That’s what we’ll explore in this post. We’ll set the stage by outlining the difference between two types of cueing strategies: internal and external. We’ll then present additional focus of attention research (a branch of motor learning theory) – and suggest a rebuttal to that research. Finally, we’ll provide additional examples to gain some clarity from a coach’s perspective.

One caveat before I continue. I played competitive tennis (the equivalent of the minor leagues in baseball) and hold a MSc degree in sport science. Given this, my role is often one of bridging the gym with the court. In other words, I can relate to both sides of the coin: the technical and tactical elements of the game, along with the off-court elements needed to be physically prepared. Eric, who I have admired for years, is someone who not only can relate to these two elements, but can also bring sports medicine into the mix.

I’m bringing this up because, first, I think that no matter where you lie on the spectrum – on the field as a skills coach or in the lab as a researcher – knowing a little bit about cueing and learning is probably a good thing so that you can have at least have a meaningful conversation about it.

Second, a lot of these principles are interchangeable with different branches of the performance world. Even physios can apply some of the research on attention and motor learning with their patients, just in a slightly different context.

Lastly, because of my experiences in tennis, a lot of the examples you’ll see in this post will stem from there. I’ll do my best to tie in other sporting examples, especially from the baseball world, but please don’t be too hard on me if I’ve made a baseball nomenclature mistake along the way.

What’s the Difference Between External and Internal Cues?

Internal

Remember the cueing examples in the intro? In tennis, we see similar ones. Things like “turn your shoulders” and “move your feet.” The commonality here is that each instruction is focused on a body segment or part.

Gabriele Wulf – prominent researcher in attention and motor learning – would say that these cues are bringing an athlete’s attention to internal factors. More specifically, she defines internally-focused cues as “where attention is directed to the action itself” (2007).

But how does a player interpret a cue like, “bend your knees?” How low should the athlete go? Is a 90-degree knee bend as effective as a 100 degrees of knee flexion? At what point in the swing/movement? Should one knee be bent more than the other?

As you can see, this cue can be interpreted in a number of different ways, depending on the athlete and the context.

Now, I’m not saying this cue can’t be used or that it’s not effective. The fact is, however, it’s got to be much more specific. For example, perhaps I want my player to load the rear leg on the forehand side to initiate a more forceful hip and trunk thrust towards the oncoming ball. So, instead of “bend your knees,” you might say, “put more weight on that rear leg during your set-up, then use it when accelerating to the ball.”

See how much more specific that is compared to “bend your knees”? You might be saying to yourself, “but that’s a pretty long cue”. Yes, it is. But we may only have to use that entire cue once (or periodically). The athlete will now understand a shortened version of it like “load that rear leg” or “add pressure to that back foot” or some similar alternative – and we’ll still end up at the same outcome.

External

Here’s an example of an athlete practicing their serve (and missing a lot) using external cues only (i.e. a target):

Orienting your attention externally, on the other hand, is described as “where the performer’s attention is directed to the effect of the action” (Wulf 2007).

To clarify, external focus instructions are aimed at factors outside the body, like an implement, support surface, the trajectory of an object, or a target. A baseball batter, for example, could direct his/her focus to the bat (its path, velocity etc), the ball (its spin, speed, trajectory etc.) or to the area of the field they’d like to hit into (target).

In tennis, hitting with depth (i.e. getting the ball to land near the opponent’s baseline) is a pretty important skill. Because in today’s day and age, if you hit just a touch short, you’ll soon be on defense. To practice this ability, we often use an externally-focused cue, and it’s usually a target. For instance, with our elite guys, we might mark a line three feet from the baseline and get them to focus on hitting the ball past the line. With younger players, a starting point for “depth training” might simply be to get the ball to land past the service line.

In this example, the cue is not only external, but it’s also distal and has an environmental component – meaning that the focus is further away from the athlete. An example of a proximally-oriented external cue would be focusing on the movement of the racquet. This would not fall under the environmental component, but what researchers call skill-oriented (i.e., we’re directly attempting to target the skill of swinging the racquet – or some sort of technical outcome).

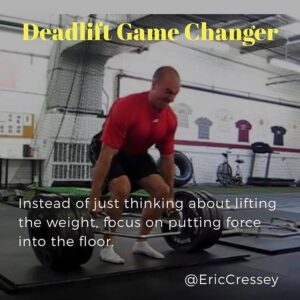

On the gym side, as we’ll see below, there’s been a fair amount of research suggesting the benefits of cueing athlete’s externally to produce more force, more power or during speed training. For example, instead of asking an athlete to use more of their legs during a countermovement jump, you might ask them to “push the ground away” or simply pick a spot on the wall (or use a basketball hoop) and see how high they can touch. I like the latter as a form of competition amongst a group of athletes (see vid below) it’s also more distal/environmental vs. proximal/skill oriented.

Here’s an example of athletes trying to touch the highest part of a ceiling during a jump.

The Theory

If you haven’t figured it out already, a lot of the recent evidence points to bringing an athlete’s attention to external – instead of internal – factors. But why is that?

According to Wulf (2013), internal focus of attention instructions contribute to a conscious awareness of the desired movement. And if we’re more conscious of what we’re doing, this will inhibit automatic processes. The opposite is true for externally-focused cues – they almost deliberately facilitate a subconscious control of movement.

One theory behind this – one which Wulf (2013) suggests – is that directing attention to a particular limb for example, will provide a neural representation of the self. The result, according to Wulf, is we over-regulate our actions.

So instead of moving with more grace, we end up increasing tension. Instead of effortlessness, our movements are rigid and more mechanical. We’ve all been there before, right? You’re given feedback to keep your wrist locked at impact, for example, and what happens? Your entire arm, shoulder, neck, etc. get tight, and you can’t even make clean contact with the ball.

But perhaps there’s a place for being more aware? To consciously move the elbow into a certain position. At least for some period of time.

What’s the Research on Attention and Motor Learning Have to Say About This?

If you’re like me – and get really hyped up about this sort of stuff – then you’re probably eager to find out, what’s the research suggesting? Which is best for learning and ultimately, performance?

In a review article by Wulf (2013) where close to 100 studies were investigated, significant differences exist between externally and internally-focused cueing across a variety of sports and disciplines

Specifically, it’s externally-focused cues that significantly and consistently outperform internal cues. Apart from a few studies that showed benefits to internal cueing – or no significant difference between the two types of cueing strategies – external seems to be the way to go.

But here’s the thing, most coaches use internally-focused cues most of the time. In fact, Porter (2010) found that 84% of track & field athletes reported that their coaches gave instructions that were specific to the movement of a body part or segment. Van der Graff et al (2018) reported a similar finding in elite Dutch league pitchers; they only heard externally-focused cues 31% of the time. If collected, I’m sure data would reveal similar findings across many sports.

Specific Research Examples

In a 2007 study on golfers, Wulf and Su found that external instructions were superior in both novices and experts. When attention was directed at the swing of the club or a target (instead of a specific movement of the arms), performance was better. Conversely, Perkins-Ceccato et al. (2003) found that internal instructions were more beneficial with less skilled golfers than more skilled golfers.

In baseball, the results vary based on a number of factors, including the skill being coached. Out of four different attentional conditions, Castaneda and Gray 2007 found that highly skilled batters performed best when attention was focused on “the flight of the ball leaving the bat.”

These same batters performed worse when attending to “the movement of their hands” where the focus was internal. Interestingly, however, the less-skilled batters performed worse when attending to environmentally-oriented external cues. These batters fared best when the attention was aimed toward the execution of the skill – and there was no significant difference between external and internal instructions. So, in less skilled performers, both internal and external cues benefited performance.

In other sports, we see more of the same (Wulf 2013). Basketball free throw shooting accuracy benefited more from external cueing vs internal – i.e. focus on the trajectory of the ball instead of the flexion of your wrist. On the performance side, agility scores were better after external cues versus internal ones (Porter et al 2010).

There’s a host of other studies that have reported better results for externally-focused groups versus internally-focused ones (Wulf 2013). Benefits include greater maximal force production, more reps being performed during a bench press test, reduced 20m sprint times, increased broad jump distances, further discus throws, and a host of others. For specifics, I direct you to Wulf’s review, Attentional focus and motor Learning – A review of 15 years.

My Counter-Viewpoint

By now, you’re probably ready to throw all your internal cues out the window and completely switch over to external cueing strategies. Before you do, hear me out.

Let me be candid for a moment. Yes, there’s some compelling evidence suggesting that directing an athlete’s focus externally is more effective compared to internally. But after dissecting some of the research, conversing with world-class coaches – and testing it with my own athletes – I’m not sure that I’m completely convinced.

Because there’s an issue with a lot of the research. First, most studies are short lived. Learning is similar to typical training adaptations; there’s often a latency period (and at times, a pretty lengthy one at that). So, we’re still not quite sure if long-term retention and learning would be better served by using external versus internal cues.

Second, most seasoned coaches employ a combination of these two cueing strategies. They assess the situation and the athlete, and then provide a cue that corresponds to the needs of that particular moment/setting.

Do you really think a basketball player will become a better shooter, in the long run, if the only thing they focus on is the target (i.e., the basket)? That improving elbow position, and sequential extension of the elbow and flexion of the wrist won’t help the player perform better, eventually? If so, I’m sorry but you haven’t been around sport enough; and in particular, you haven’t seen less skilled athletes evolve their skills.

Sure, tell the basketball player to “flick the wrist” after releasing the ball and you’ll probably see them tense up certain muscles…initially. But over time, as that movement becomes automated, and they now have the ability to add spin and height to their shot, those muscles will eventually relax. And now tell that player to focus more on the hoop.

Personally, I believe there’s a constant tug and pull, a back and forth, a mix and match type scenario that should occur. Sometimes, we need to focus on the positioning and/or execution of a particular body part. Other times, we should focus more on an external factor like the flight of the ball or a target. But this will all depend on the athlete, their preferences, their skill level, the time of year, the complexity of the task, the sport in question, and probably a host of other factors I haven’t yet considered.

My Experiences and Personal Observations with Cues

1. With beginners, I’ve used a mix of strategies from day 1. I have never been a fan of a kid standing in line waiting to hit a tennis ball from a stationary position. So instead, we would try to get kids rallying as quickly as possible. And a good way to do that would be to get them to focus on some external cues first. Drills that would help with the perception of an oncoming ball, the trajectory of the ball, a target, focusing on bouncing the ball off the string bed and so on. Then, we would try to tie in some interna’ cues to help them rally with more power, get more spin and so on. Things like “get your chin to touch your front shoulder” to facilitate more of a shoulder turn worked well.

2. In certain cases, external cueing can be more beneficial when approaching competitions. Many tennis players I’ve coached don’t want to hear anything about “traditional” technical cues (e.g., arm position, leg drive) when a big match is around the corner. In these instances, I’ve found that talking more about targets and trajectories works well. Things like “add shape” (using my hands to show the shape I’m looking for) to the ball might help to get more height (and safety) over the net. “Aim for the baseline” might help achieve more depth on shots when players are hitting short. Those types of external cues are also more distal – which get players thinking even less about their bodies (and letting automation take over).

3. While most players I’ve worked with don’t want to hear much about technique during competition time, there are some that need that type of feedback. In most cases, keeping cues familiar and simple has worked best. The key though, is that it should be specific to that player, and what you’ve been working on (and reinforcing) of late. For instance, one of my “minor league” pro guys was getting stuck with his forehand. He just wasn’t creating enough space between his elbow and his torso, which took some power off the swing (less leverage). We tried many cues but what worked for him was the feeling of getting his elbow “straighter” at contact (even though it was never completely straight). This actually forced him to prepare a little sooner, so that he could strike the ball earlier (more in front), which led to more distance between his elbow and torso (and all the other benefits – kinematically – that come with that) and which resulted in more speed on his forehand. This internal cue (“get that elbow straighter at impact”) worked for this player, no matter the time of year (even hearing it during the warm-up before a match helped).

4. I believe that some of the externally-focused cueing has been blown way out of proportion. On certain tasks, do we really need to bring an individual’s attention to an external source? Here’s an example I heard recently that a coach was cueing an athlete’s stance during a squat and said, “Imagine you’re standing on two railway tracks.” Really? Can we not just say, “stand shoulder width apart”? Is that going to make a big difference? Perhaps a cue like “I want to see your shirt logo during the entire squat” could help an athlete maintain better trunk positioning…but some athletes might be just fine with, “Keep your chest up”. As you can see, a lot of this is probably very athlete-dependent, which means a coach needs to know their athlete. And a lot of the cueing will be trial/error. And I think that’s completely fine!

5. One cue in, one cue out. This has been a game-changer for me, as I believe certain athletes are intelligent individuals and can process more than one cue at a time. For this to work well, tell the athlete to focus on one cue at the beginning of a movement – usually internal. And then one cue after that movement, or during the execution portion – usually external. For instance, during a jump, you might tell an athlete to “swing the arms back” as they are loading the movement and then ask them to “push the ground away” just prior to the propulsive (jumping) phase. The same can probably be done with swinging a racquet and hitting a baseball – keep the elbow [insert internal cue] during the prep phase and aim for the [insert external cue] when in the midst of striking.

6. The type of sport matters. Running, track, strength training, all have less opportunities for external focus cues compared to open-skilled sports like tennis and baseball. Therefore, it’s no wonder that more track coaches employ internal vs external cues with their athletes; there’s logic to that. Tennis and baseball, on the other hand, probably allow us to use a bit more externally-focused cueing strategy and just let the athlete go at it for a while.

Wrapping it Up…And What’s Next

I’ve heard the argument from researchers before – because most coaches use internal cues instead of external cues, athletes are accustomed to them and prefer them. But I’m not entirely convinced of this. Many elite settings – like Cressey Sports Performance, Altis, and others – have coaches who understand and employ both.

Either way, as you’ve noticed, I don’t believe we should use one type of cueing exclusively. Both have their place. Dan Pfaff, an elite tack coach (and mentor of mine), offered me this advice: “Most successful coaches are the ones that know when to use one over the other, and how to tread that line.”

He also mentioned that the timing/frequency of cueing – when, how often, etc. – is equally, if not more important. And when it comes to internally-focused cues, maybe that’s the issue. Maybe it’s tough to learn when you’re hearing five different cues in the span of ten seconds? But that’s a whole other can of worms…one we’ll explore in a follow-up post.

Note from EC: if you’re looking to dig a bit deeper on this topic, I’d highly recommend you check out this podcast I did with Nick Winkelman:

About the Author

Matt Kuzdub, MSc, (@CoachKuzdub) is best known for creating www.mattspoint.com – an online platform for all things tennis training – including coaching, resources and ebooks. He also coaches a small group of elite players (college & pro), both on and off the tennis court. Previously, Matt was the lead sport scientist at ‘Train with PUSH’ and holds an MSc in Strength & Conditioning from the University of Edinburgh. You can follow him on Instagram at @mattspoint_tennis.