Assessments You Might Be Overlooking: Installment 6

It’s been quite some time since I published an update to this series, but some recent professional baseball initial offseason evaluations have had me thinking more and more about how important it is to take a look at lateral flexion.

In the picture above, I’d say that the athlete is limited in lateral flexion bilaterally, but moreso to the left than right. You’ll also notice how much more the right hip shifts out (adducts) as he side bends to the left; he’s substituting hip fallout for true lateral flexion from the spine. The most likely culprit in this situation is quadratus lumborum on the opposite side (right QL limits left lateral flexion).

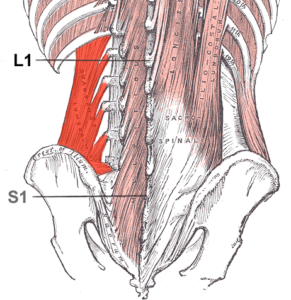

As you can see from the picture below, the triangle shaped QL connects the base of the rib cage to the top of the pelvis and spine.

Stretching out the QL isn’t particularly challenging; I like the lean away lateral line stretch (held for five full exhales). This is a stretch that can be biased to target the lat, QL, or hip abductors.

That said, the bigger issue is understanding why a QL gets tight in the first place. As Shirley Sahrmann has written, whenever you see an overactive muscle, look for an underactive synergist. In this case, the right glutes (all of them) are likely culprits. If the gluteus maximus isn’t helping with extending the hip, the QL will kick on to help substitute lumbar extension. And, if the gluteus medius and minimus aren’t doing their job as abductors of the hip, the QL will kick in to “help out” in the frontal plane. This double whammy has been termed a Left AIC pattern by the good folks at the Postural Restoration Institute, and they’ve outlined many drills to not only address the apical expansion (which creates length through the QL), but also bring the pelvis back to neutral.

Taking this a step further, typically, those with very overactive QLs will also present with limited thoracic rotation (in light of the QL attachment on the inferior aspect of the ribs), so you’d be wise to follow up this stretch with some thoracic mobility work. The athlete in the example at the top of this article had the most limited thoracic rotation (both active and passive) that I’ve seen in any pitcher this offseason.

That said, here’s a good rule of thumb:

If you have a flat thoracic spine athlete with limited thoracic rotation, look at pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and quadratus lumborum. If horizontal abduction (pec) and shoulder flexion (lat) both check out well, go right for QL tissue extensibility (as measured by lateral flexion). It will be absolute game changer – particularly in rotational sport athletes.

If you’re looking to learn more about how we assess, program, and coach at the shoulder girdle, be sure to check out my popular resource, Sturdy Shoulder Solutions.