We welcome Texas Rangers team doctor and renowned orthopedic surgeon Dr. Keith Meister for a conversation on baseball’s injury epidemic. Dr. Meister shares how injuries have evolved in the […]

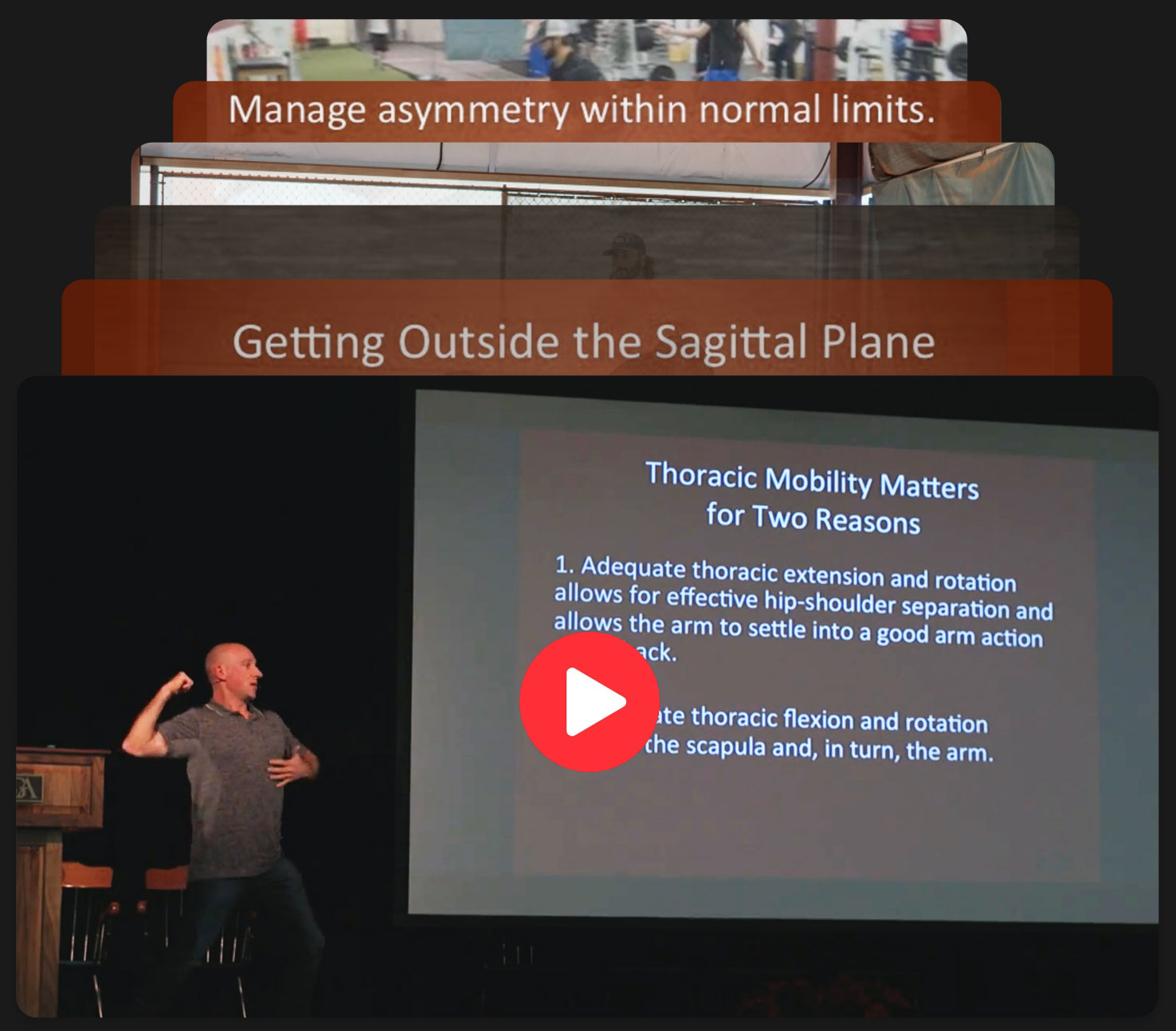

Free Access to Eric’s 47-Minute UNE Lecture

Hip-Shoulder Separation in Rotational Athletes: Making Sense of the Thoracic Spine.

Welcome to Cressey Sports Performance

Over the years, Eric Cressey’s given this lecture to more than 10,000 coaches, players, sports medicine professionals and enthusiasts and it’s been a huge hit. In the video, you will observe a lot of our CSP athletes training and learn: