This week’s Pinch Hit Friday is now live. In this episode, I dig in on the concept of “scap loading,” a portion of the pitching delivery that’s been heavily […]

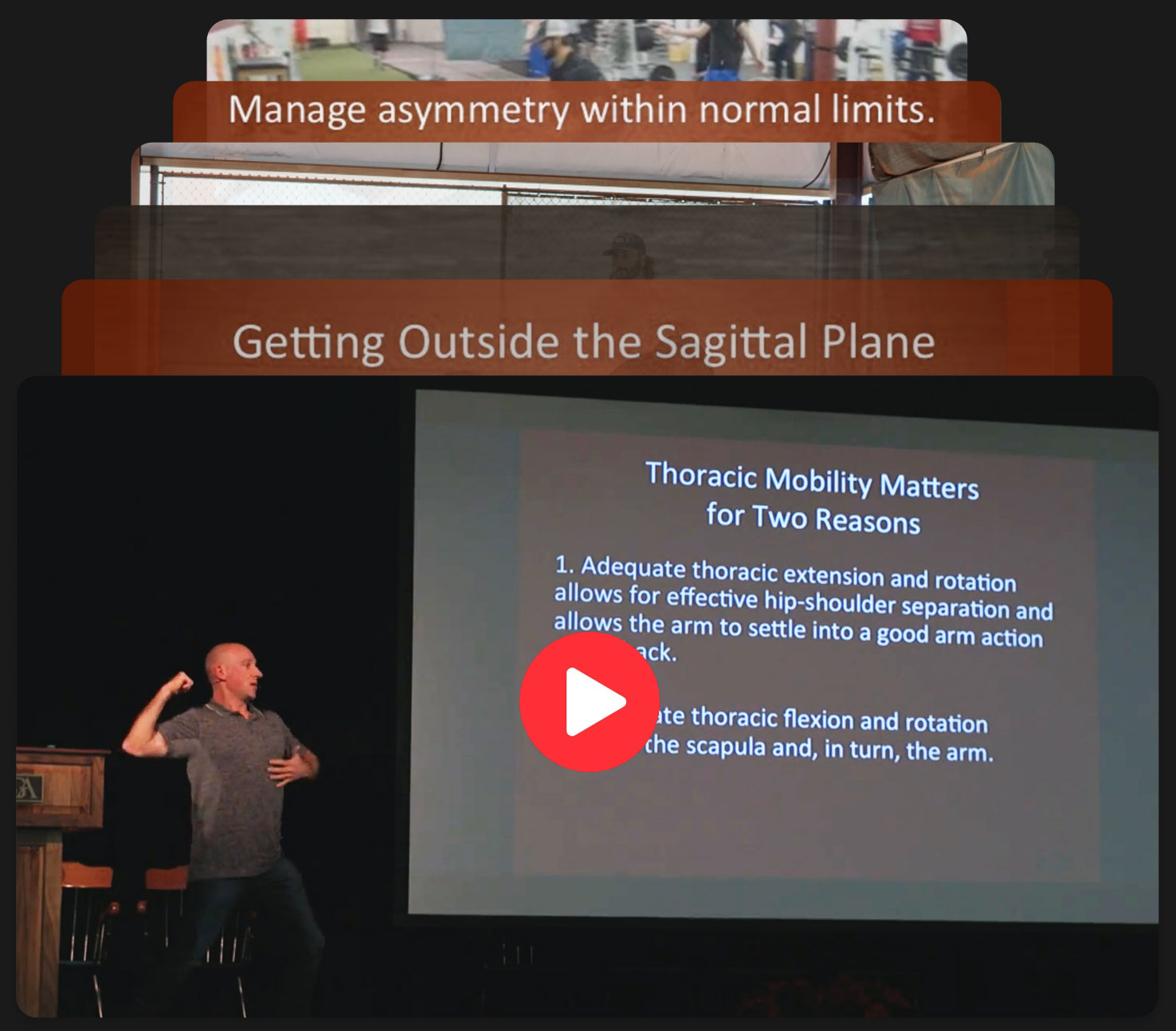

Free Access to Eric’s 47-Minute UNE Lecture

Hip-Shoulder Separation in Rotational Athletes: Making Sense of the Thoracic Spine.

Welcome to Cressey Sports Performance

Over the years, Eric Cressey’s given this lecture to more than 10,000 coaches, players, sports medicine professionals and enthusiasts and it’s been a huge hit. In the video, you will observe a lot of our CSP athletes training and learn: