How to Win 99% of High School Baseball Games

I’ve never coached a high school baseball game – or any game, for that matter. I have, however, worked alongside some tremendous high school coaches – from my time with Team USA, to our five staff members who’ve coached, to various close friends. And, I’ve watched more high school baseball games than I can possibly count (my fourth date with my wife was a high school state championship game in 2007). So, I feel reasonably qualified to comment on this topic – and I’ve run this theory by several accomplished coaches who have all agreed.

I’m of the belief that high school baseball games are rarely won; rather, they are lost. Usually, the mistakes far exceed the outstanding play, and the team who makes fewer mistakes invariably ends up on top. As Cressey Sports Performance – MA pitching coordinator Christian Wonders has said, “you have to win the free base war.”

With that said, bear with me as I outline five things that virtually guarantee you wins in high school baseball.

1. Have a catcher who can receive/block.

There is nothing more painful to watch than a CATCHer who can’t CATCH or block. It derails an entire game because you immediately take away a pitcher’s confidence (impacting #5 from below) and have him worried about the running game all the time. The good news is that receiving and blocking is highly trainable – and in a relatively short amount of time – with good instruction as long as you have a player who isn’t afraid to put in the work and roll around in the dirt. And, elite arm speed isn’t necessary behind the plate at the high school level. This quality is highly trainable.

2. Make the throws and catches you’re expected to make – and don’t throw the ball around.

You don’t need to have Andrelton Simmons’ range or arm to be a good high school defender; you just need to be intelligent enough to not make big mistakes in overestimating your abilities. I’m a huge believer that paying strict attention to good, aggressive catchplay during the warm-up period pays big dividends in this regard. Most high school kids just shoot the breeze during inattentive catchplay, and most coaches rush the long toss period because they’re anxious to get to other stuff during practice. This quality is highly trainable.

3. Have strong kids that can hit the ball hard.

This is where I’m going to nerd out a bit. If you hit the baseball hard, you will get on base more often. It’s follows logically, but with the increased focus on exit velocity in MLB in recent years, we can more easily quantify it. Take a look at the huge, linear relationship between exit velocity and batting average (not to mention the concurrent increase in HR percentage):

This shouldn’t surprise you: a greater exit velocity will always enable balls to find more holes and gaps, and put more pressure on the defense to induce more errors (especially in high school baseball, where many young athletes are still legitimately afraid of the ball). I can guarantee you that the averages probably go up an additional 150-200 points in the high school game because defenders don’t have as much range, parks are smaller, infields aren’t as smooth, and a host of other factors. How realistic is it for high school hitters to attain these exit velocities? I asked my buddy Bobby Tewksbary, and he sent this along to me:

“High school exit velocities vary greatly depending on many factors like weight, strength, speed and skill. Using HitTrax, we see high school freshmen who are still prepubescent and struggle to break 70 mph. On the upper end, we recently had a high school junior hit a ball 108 mph. This is on par with – or higher than – our pro clients. Most varsity players are in the upper 80s to low 90s. Anything above 100 mph is usually reserved for D1 caliber players. As an example, we recently had a senior D1 commit (on HitTrax) hit a ball 106.4 mph and 481 feet.”

Obviously, this doesn’t take into account that you actually have to face live pitching, but if you’re a high school hitter consistently hitting the ball 90mph+ in games, you can bet that you’ll be hitting at a .400 clip.

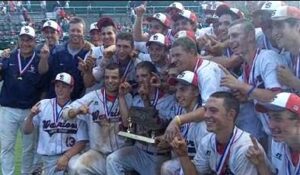

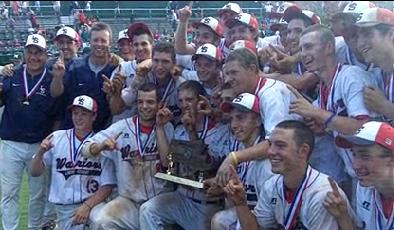

As a frame of reference, the best Cressey Sports Performance “attendance” from a single team was the 2011 Lincoln-Sudbury (L-S) Regional High School baseball team that won the Massachusetts state championship. Of the 25 kids on the roster, 24 trained at CSP – and they hit .361 on the season. They scored 61 runs in six games in the playoffs. Strong players who prioritize strength and conditioning – especially in-season – hit balls hard and win a lot of games. This quality is highly trainable.

4. Run the bases aggressively/intelligently.

This is the single biggest window of adaptation and untapped competitive advantage in a high school population because a) very few coaches understand how to teach it, b) even fewer prioritize it, and c) 99% of players have easy adjustments they can make to set-up, sprint mechanics, and strategy that differentiate them quickly. With the number of walks, dropped third strikes, errors, passed balls, wild pitches, and balks we see in high school baseball, having a relatively fast, intelligent athlete on the bases is a game changer. The best athletes run wild on mediocre defenses. As a frame of reference, that same L-S team I highlighted above actually stole 81 bases in 28 games (seven innings each); that basically works out to a stolen base almost every other inning. This quality is highly trainable.

5. Have strike throwers on the mound.

Velocity is awesome and it’s great to train it. The problem is that a lot of hard throwing high school arms have no idea how to harness it to command the baseball. I’ve seen a lot of 86-88mph arms get yanked in the second inning after seven walks while getting outpitched by a 70-poo mph arm that throws strikes. Don’t misinterpret what I’m saying, though: velocity is really useful (especially at the next level), but in high school, it doesn’t impact outcomes nearly as much because other teams rarely have hitters that accomplish #4 from above (hitting the ball hard). In other words, you see far more games lost by crappy teams than you do games won singlehandedly by elite arms. The L-S team from earlier took 127 walks in 196 innings while only striking out 110 times. Meanwhile, their pitching staff (which included two D1 arms, including future Vanderbilt closer and 4th round draft pick Adam Ravenelle) punched out 254 guys while walking 110. If you put up a 2.5: 1 K:BB ratio in high school baseball, you’re going to win a lot more games than you lose. This quality is highly trainable, although not quite as much as some of the others from above.

Bringing It Together

Go to most high school practices, and you’ll see a lot of time wasted. You’ll see a lot of guys standing around in the outfield shagging BP. You’ll watch the mind-numbing slow jog around the field during the warm-up, or some underwhelming static stretching in a circle. You’ll want some pre-throwing drills – wrist flicks and half-kneeling work – that can probably be skipped. It may be excessive time spent on every obscure situational defense scenario with lots of guys standing around. In other words, there is a lot of time that can be “repurposed.”

How do you use this time better?

1. Work with your catchers. Don’t just beat them like rented mules; challenge them and teach them.

2. Teach baserunning and sprint mechanics, and run the bases hard.

3. Prioritize and coach the heck out of catch play. Don’t rush long toss.

4. Emphasize strength and conditioning year-round, and don’t let it fall off inseason.

5. Give pitchers consistent developmental challenges. Actually schedule bullpens and have an expectation for what is to be worked on and achieved in each one.

You win games focusing on big rocks, not majoring in the minutia where there aren’t large windows of growth possible.

*A special thanks to Coach Kirk Fredericks for not only pulling all these statistics together for me, but for teaching me a lot of these things over the years. Kirk went 269-68 with three state titles in 14 years as a head coach at L-S and is one of the best coaches I’ve seen at any level. I’m lucky to have him as a resource.