Stop Thinking About “Normal” Thoracic Spine Mobility

Years ago, I published a post, Tinkering vs. Overhauling – and the Problems with Average, where I discussed the pitfalls of focusing on population averages, especially in the world of health and human performance. I’d encourage you to give it a read, but the gist is that you have to be careful about overhauling a program because you see someone as being outside a “norm” that might have been established for an entire population when they are unique in so many ways.

Thoracic spine mobility is an excellent example. What would be considered acceptable for an 80-year-old man would be markedly different than what we’d want from a 17-year-old teenage athlete in a rotational sport. This athlete, for instance, had some marked negative postural adaptations that contributed to two shoulder surgeries during his time as a baseball pitcher. If he was far older with different physical demands, though, he might have never run into problems.

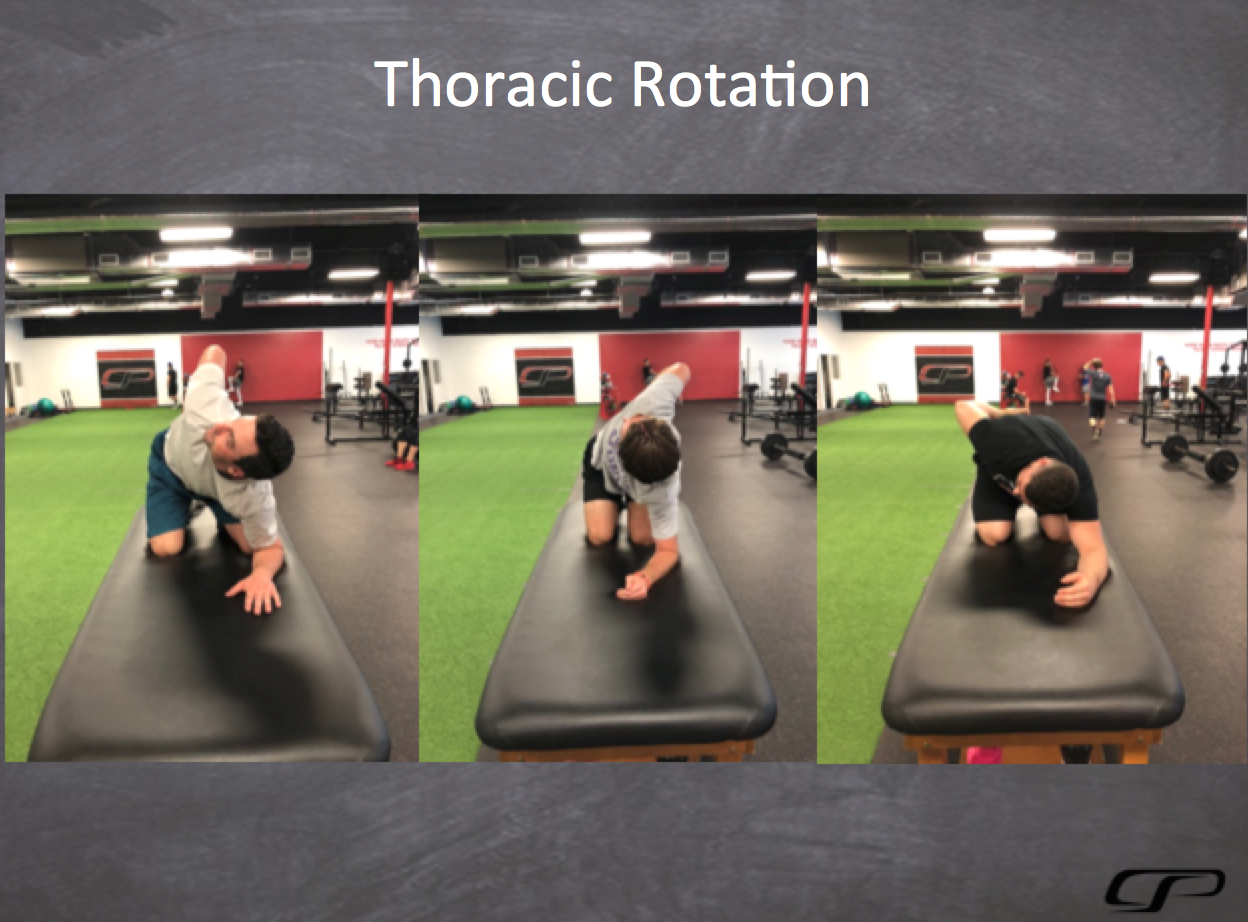

Lumbar locked rotation is a great thoracic spine rotation screen I learned from Dr. Greg Rose at the Titleist Performance Institute. Briefly, you put the lumbar spine in flexion (which makes lumbar rotation hard to come by) and the hand behind the back (to minimize scapular movement). This allows you to better evaluate thoracic rotation without compensatory motion elsewhere. Check out the high variability among three athletes who are all roughly the same age:

On the left, we have a professional baseball pitcher. In the middle, we have an aspiring professional golfer. And, on the right, we have a powerlifter who’s moved well over 600 pounds on both the squat and deadlift. Adaptation to imposed demand is an incredibly important part of this discussion of “normal.” The hypertrophy (muscle bulk) that benefits the powerlifter could possibly make the baseball pitcher and golfer worse, but at the same time, I wouldn’t necessarily say that the powerlifter is “lacking” in thoracic rotation because you don’t need a whole lot of movement in this area for a successful, sustainable powerlifting career.

I should also note that these are all active measures. If we checked all three of these guys passively, we’d likely see there’s even more thoracic rotation present than you can see here. And, that can open up another can of worms, as having a big difference between active and passive range of motion can be problematic, too.

The take-home message is that if you’re going to call someone’s movement quality “abnormal,” you better have a clear designation of what “normal” is for their age and sport, as well as what’s required for their athletic demands.

For more information on how we assess and train thoracic mobility, I’d encourage you to check out my popular resource, Sturdy Shoulder Solutions.