Periodization for Teenage Athletes: Part 2

This is part 2 of Cressey Sports Performance coach John O’Neil’s look at periodization for teenage athletes. In case you missed part 1, you can check it out HERE. -EC

When assessing a youth athlete, the most important information we can gather isn’t the only the specific or general movement-based assessments we run. The importance lies in the questions we ask and our ability to judge what kind of training program for which the athlete is ready. If we assume too simple, it’s easy to still see progress and transition to a more advanced program. Conversely, if we assume too complex, we’ve not only stalled progress, but we’ve potentially caused a host of issues – both physically and psychologically – that we will have to address. The industry is full of people using overly complex methods with people who haven’t earned them yet. Don’t be that guy.

Here are the main points I focus on in making this distinction:

- Age

- Actual age: If they’re under 16, it’s definitely going to be a concurrent program, and 16-18 year olds maybe approached the same, based on the answers to the following questions:

- Biological age: How physically mature are they? Do they present like their actual age?

- Training age: Have they trained for any period of 6 months – or multiple 3-month periods?

- Athletic Skill Level

- How far off from being an elite athlete are they? In our setting, throwing velocity for pitchers is often the determinant of this question.

- At what level do they compete athletically? Chances are that your middle school, freshman, and JV level players don’t need anything fancy.

- Personal Maturity

- This one is much harder to quantify, but a typical fail in this category would include the kid who has his/her mom do the talking for them, or, someone who has no quantifiable goals and has no idea why they’re training.

- Will they follow a program to a “T?” Or, is this an individual who’ll cut corners and omit the items he/she doesn’t enjoy?

Concurrent Programming Overview

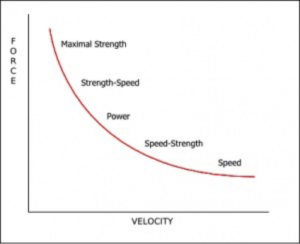

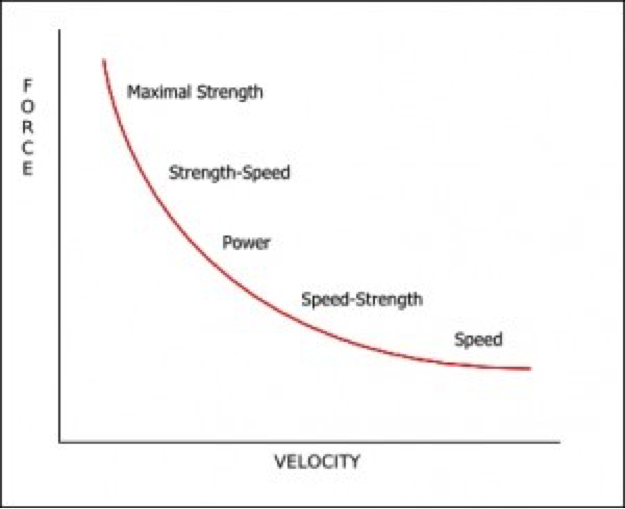

If we look at a force/velocity curve, it’s our job as strength coaches to shift the curve up and to the right as much as we can. When we have a beginner athlete, every quality needs to move in that direction, independent of their sport or time in their competitive calendar. If we look at each quality as a bucket, all of these are empty and we need to fill each of them up. With advanced athletes, we need to assess which buckets are already filled and which buckets are the most empty. The empty buckets need to be filled up for the person to become a better athlete, and we need to consider their competitive calendar. The later in the offseason it is, the more closely the exercises we choose and speeds we prescribe will we need to reflect the movements they’ll actually encounter in sports. With beginner athletes, this doesn’t matter as much.

Strength-speed and speed-strength are also not qualities that we’ll focus on in beginner concurrent model programming. These are more advanced concerns. In beginners, we’ll stick with strength, power, and speed as our big three. Each of these three qualities are going to be trained somewhat equally during an athlete’s first 3-6 months. Chances are these athletes aren’t coming in six days per week, so we will hit each of these qualities every time they walk in the door. A typical session will include a dynamic warm-up, speed work, power work, 1-2 technical lifts, and 4-6 GPP style movements done in a more circuit-based fashion.

In block periodization, there is a phase of accumulation, a phase of transmutation, and a phase of realization. In concurrent periodization, our goal is to accumulate, accumulate, and continue to accumulate strength, power, and speed until we have deemed the athlete ready for more advanced programming.

Exercise Selection

When selecting exercises, there needs to be some form of linear exercise progression that begins with the exercise that is easiest for the athlete to not only learn quickly, but to load in the safest and most efficient manner possible. Lowest barrier to entry is a great term to summarize the exercise selection for this period. Pick movements that are hard for the athlete to screw up. We are looking to pick the exercise that combines the two following principles:

1) Can the person master the technique in an efficient and timely manner? How quickly can we make this exercise safe?

2) Can the person load the exercise in a way that progresses their main performance qualities – strength, power, speed – without technical difficulty of the exercise itself stalling progress?

External load should be the limiting factor for an appropriate exercise progression, as opposed to an athlete being held back by an inability to handle the implement being used (dumbbell, kettlebell, bar).

[bctt tweet=”Limiting the learning curve may be the safest and most effective way to maximize the loading curve.”]

There’s nothing wrong with keeping a main exercise the same for 12-16 weeks in a beginner. Provide variety in your dynamic warm-ups and unloaded exercises, not your staple loaded exercises. If your reason for programming variety is fun, maybe you should look at your training environment and your personal relationships with the athletes instead of choosing loaded variety to make the athlete enjoy training more. Especially in beginners, everything involving external loading should have a reason; picking a loaded exercise for fun is an asinine reason to program it.

I have these progressions mapped out for each main movement, with a theoretical end point before you change an exercise. For a squat, my progression is as follows:

• Goblet Squat to Box – until the person has awareness of and has owned the bottom position

• Goblet Squat – until the grip becomes the limiting factor towards loading the lower body

• 2KB Squat – until the person can complete sets of 8-10 with 16/20kg bells

• Safety Squat Bar (SSB) Squat – until someone can load 1.5xBW for sets of 3-5

*An athlete might do a front squat in the same spot as an SSB, but I usually find that the SSB is easier for athletes to learn first. We don’t back squat our baseball guys, but other athletes may progress up the chain to that exercise, especially if they’ll have to do it at school.

While these guidelines of progression don’t need to be adhered to strictly, sometimes I will veer off the Goblet or 2KB squat if I think the athlete is either ready for something else for or has stalled on an exercise. My point is simply that it’s important to have general guidelines for progressing exercises in beginners. The key is to make sure you’re not putting someone under a bar when they’re not comfortable with the technique of both the setup and the action.

This is not only true on loaded exercises, but for sprints, jumps, and throws as well. Many sport coaches these kids will have will crush them with lactic work: repeated sprints with inappropriately assigned rep schemes, distances, and rest times – but very few athletes we evaluate have ever been taught a thing about how to sprint more efficiently. As an industry, I think that we have a good understanding of lifting progressions, but power and sprint work isn’t as highly prioritized. If we look at the qualities of the best athletes – the fastest and most powerful with the best rate of force development, but not necessarily the highest strength – this doesn’t make any sense. We need to prioritize these qualities from a young age, at least from a technical proficiency standpoint.

The same principles of technical mastery, erring on the side of too simple and then progress, and lowest barrier of entry apply to sprint, jump, and throw training. While these concepts open up another broad topic, my initial block progressions in a beginner concurrent model are as following:

• Sprints: Work on mastering arm action, marching, and skipping

• Jumps: Learn how to decelerate bilaterally in the sagittal plane before getting into unilateral work, frontal/transverse plane, accelerative and reactive jumps

• Throws: Stationary sagittal plane work, focus on intent and outcome-oriented throwing before going transverse plane and increasing complexity

In part three of this series, I’ll take a deeper dive into how we program using a conjugate method of periodization for our athletes with a higher training age.

About the Author

John O’Neil (@ONeilStrength) is a coach at Cressey Sports Performance-MA. You can contact him by email at joh.oneil@gmail.com and follow him on Instagram.