What the Strength and Conditioning Textbook Never Taught You: Synergists and Antagonists

As a follow-up to yesterday’s “series premier,” I wanted to use today’s post to discuss another topic that rarely gets sufficient attention in the typical exercise science textbook: synergists and antagonists.

The typical explanation of the relationship of the two is that they’re on opposite sides of the joint and perform opposite actions. As an example, the hamstrings flex the knee, and quadriceps extend the knee. Simple enough, right? Not so much.

Muscles can be synergists and antagonists at the same time.

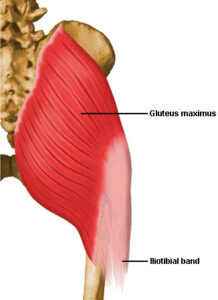

Let’s just look at the hip extensors to explain this point. Your primary hip extensors are the hamstrings, gluteus maximus, and adductor magnus (there are more, but we’re keeping this discussion simple). They all work together to extend the hip each time you squat, lunge, deadlift, sprint, push the sled, or bust a move on the dance floor. That said, the hip can do a lot of things as it extends.

If we use more gluteus maximus and biceps femoris, it externally rotates and abducts a bit as we extend. If we use more adductor magnus, semitendinosis, and semimembranosus, it internally rotates and adducts.

Taking it a step further, as the hamstrings extend the hip, they have little control over the femoral head, so it tends to glide anteriorly in the acetabulum (hip socket) in a hamstrings-dominant hip extension pattern. The glutes have more direct control over the femoral head and can posteriorly pull the head of the femur to avoid anterior hip irritation (usually the capsule). Shirley Sahrmann did a great job of outlining femoral anterior glide syndrome in her landmark book, Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes.

Herein exists the issue: typical discussions of synergists and antagonists focus on things things:

1. Single planes of motion (sagittal, frontal, transverse), but not the interaction of multiple planes

2. Osteokinematics (gross movement of bones at joints: flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, internal/external rotation), rather than arthrokinematics (smaller movements at joint surfaces: rolling, gliding, spinning)

3. Active restraints (muscles, tendons), but not passive restraints (ligaments, bones, labra, intervertebral discs) that may be synergists to them in creating stability

As another example, think about stabilization at the glenohumeral (shoulder’s ball and socket) joint. There are a wide range of movements taking place, yet these movements must be controlled arthrokinematically in a very precise range via a complex system of checks and balances at the joint. If the active restraints (primarily the rotator cuff) don’t do their job, one could wind up with stretched/torn ligaments, a torn labrum, or bony defects. In other words, it isn’t a stretch (no pun intended) to say that muscles can be synergists to ligaments. Put that in your osteokinematic pipe and smoke it!

This is really a topic that deserves far more than a 500-word post; it could be an entire college curriculum in itself! And, the more you can understand it, the better you’ll be able to help your clients and athletes. A great resource to get the ball rolling in this regard is Building the Efficient Athlete, a two-day seminar Mike Robertson and I filmed with functional anatomy heavily in mind.