Understanding Elbow Pain – Part 1: Functional Anatomy

Today’s piece kicks off a multi-part series focusing specifically on the elbow. I’m going to start off this collection by talking about the anatomy of the elbow joint, but in appreciation of the fact that a lot of you are probably not as geeky as I am, I’ll give you the Cliff’s Notes version first:

The elbow is the most “claustrophobic” joint in the body; there is a lot of stuff crammed into very little space. This madness is governed not just by the joint itself, but (like we know with all joints) by the needs of the forearm/wrist and what goes on at the shoulder and neck.

Even for the geeks out there, in the interest of keeping this thing “on schedule,” I’m just going to focus on your pertinent information. I would highly recommend The Athlete’s Elbow to those of you interested in learning more; it’s insanely detailed.

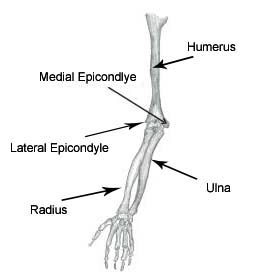

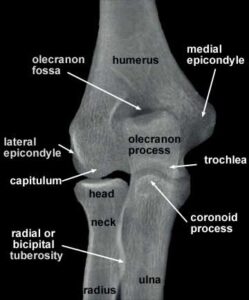

Your big players on the osseous (bone) front are going to be the humerus, ulna, and radius. At the humerus, in the context of this discussion, all you really just need to pay attention to are the medial and lateral epicondyles, as they are crucial attachment points for both tendons and ligaments (as well as sites of stress fractures in younger athletes).

Posteriorly, you’ll see that olecranon process of the ulna sits right in the olecranon fossa of the humerus. This is a pretty significant region, as it gives the elbow its “hinge” properties and prevents elbow hyperextension. Fractures of the olecranon can occur and leave loose bodies in the joint that will prevent full elbow extension. And, not to be overlooked is the attachment site of the triceps (via a common tendon) and anconeus on the olecranon process.

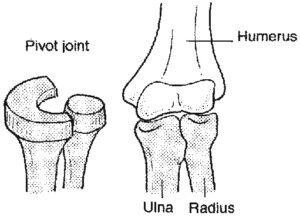

The “elbow” may just be a hinge to the casual observer, but in my eyes, it’s important to distinguish among the humeroulnar joint (described above) and the humeroradial (pivot) and proximal radioulnar joints – which give rise to pronation and supination.

Likewise, the wrist (and the fingers, for that matter) is directly impacted in flexion/extension, radial deviation/ulnar deviation, and pronation/supination by muscles that actually attach as far “north” as the humerus. Muscles aren’t just working in one plane of motion; they’re working for or against multiple motions in multiple planes.

In all, you have 16 muscles crossing the elbow. For those counting at home, that’s more than you’ll find at another “hinge” joint, the knee, in spite of the fact that the knee is a much bigger joint mandating more stability. More muscles equates to more tendons, and that’s where things get interesting.

As any good manual therapist, and he’ll tell you that soft tissue restrictions occur predominantly at:

A. Areas of increased friction between muscles/tendons

B. Areas where forces generated by a myofascial unit come together (termed “Zones of Convergence” by myofascial researcher Luigi Stecco): this is generally the muscle-tendon-bone “connection,” as you don’t typically see prominent restrictions in the mid-belly of a muscle.

This is a double whammy for the muscles acting at the elbow. In terms of A, you have many muscles in a small area. Most folks overlook the importance of B, though: a lot of them share a common (or at least directly adjacent) attachment point. The flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, palmaris longus, and flexor digitorum superficialis all attach video the common flexor tendon on the medial epicondyle, with the pronator teres attaching just a tiny bit superiorly. There’s ball of crap #1.

![]()

Ball of crap #2 occurs at the lateral epicondyle, where you have the common extensor tendon, which is shared by extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi ulnaris, supinator, extensor digitorum, and extensor digiti minimi – with the extensor carpi radialis longus attaching just superiorly on the lateral supracondylar ridge. Ball of crap #3 can be found posteriorly, where the three heads of the triceps converge to attach on the olecranon process via a common tendon, with the much smaller anconeus running just lateral to the olecranon process. You can see both balls of crap (double flusher?) coming together here:

![]()

Ball of crap #4 is a bit more diffuse consisting of the attachments of biceps brachii (radial tuberosity), brachioradialis (radial/styloid process), and brachialis (coronoid process of ulna) on the anterior aspect of the forearm.

This last graphic demonstrates that there are a few other factors to consider in this already jam-packed area. You’ve got fascia condensing things further, and you’ve also got a blood supply and nerve innervations – most significantly, the ulnar, median, and radial nerves – passing through here. The median nerve, for instance, passes directly through the pronator teres muscle.

Oh, and you’ve also got ligaments mixed in – some of which are attaching on the very same regions that tendons are attaching. The ulnar collateral ligament attaches on the medial epicondyle in close proximity to the flexors and pronator teres, for instance. These ligaments are heavily reliant on soft tissue function to stay healthy. As an example, flexor carpi ulnaris is going to be your biggest “protector” of the UCL during the throwing motion.

So what’s the take-home message of this functional anatomy lesson? Well, there are several.

1. Lots of stuck is packed in a very small area.

2. When things are stuck together, they form dense, fibrotic, nasty balls of crud.

3. These gunked up muscles/tendons can impact everything from nerve function to ligamentous integrity – or they can just give out in the form of a tear or tendinopathy.

4. Diagnosis can be tricky because all the potential issues take place in a small area, and may have very similar symptoms. Different pathologies take place in different athletic populations, too. We’ll have more on this in Understanding Elbow Pain – Part 2: Pathology.

Related Posts

Why Do Some Guys Come Back to Pitch Better After Tommy John Surgery?

Things I Learned from Smart People: Installment 2

Click here to purchase the most comprehensive shoulder resource available today: Optimal Shoulder Performance – From Rehabilitation to High Performance.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Baseball Newsletter and Receive a Copy of the Exact Stretches

used by Cressey Performance Pitchers after they Throw!