15 Static Stretching Mistakes

One of the most debated topics in the strength and conditioning world in recent years has been whether or not static stretching is necessary and, if so, when it should be implemented. While I don’t think everyone needs it, and that there are certainly are times when it is a bad idea to utilize, I’m still of the mindset that it can have some solid benefits when implemented properly.

Unfortunately, like all training initiatives, some people do it all wrong. To that end, I wanted to devote today’s article to covering the top 15 static stretching mistakes I encounter.

Mistake #1: Stretching through extreme laxity.

This is the most important and prevalent one of all, so it comes first. When I see someone doing this, this is pretty much how I feel:

We’re all have a different amount of congenital laxity. Basically, this refers to how much “give” our ligaments have. Some folks have naturally stiff joints, and others have very loose joints. This excessively joint laxity is obviously much higher in females and younger populations, but, as Leon Chaitow and Judith DeLany discuss in Clinical Applications of Neuromuscular Techniques: Volume 1, it is also much higher in folks of African, Asian, and Arab origin.

When you take someone who is really lax and implement aggressive static stretching, it’s on par with having someone with a headache bang his/her head against a wall. It makes things worse.

This is a tricky thing to understand, though, because many of these “loose” individuals will comment on how they feel “tight.” Usually that tightness is just them laying down trigger points as a way for the body to create stability in areas where they are chronically unstable. They’d be better off working on stability training to get back to efficient movement.

I think yoga has a tremendous amount of applications and we borrow from the discipline all the time, but I think this is where many modern yoga classes fall short; they have everyone in the class go to the same end-range on certain exercises. Folks with serious joint laxity should not only contraindicate certain yoga poses, but also modify others so that they’re training stability short of the true end-range of their joints. Unfortunately, most of the people you’ll see in yoga classes are hypermobile women; you see, they like to do the things they’re good at doing, not necessarily what they need to do.

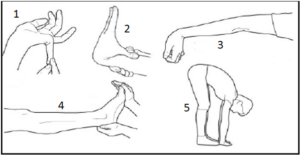

How do you know if you’re lax, though? I like to use the Beighton hypermobility scale to assess for both generalized congenital laxity and specific laxity at a joint. The screen consists of five tests (four of which are unilateral), and is scored out of 9:

1. Elbow hyperextension > 10° (left and right sides)

2. Knee hyperextension > 10° (left and right sides)

3. Flex the thumb to contact with the forearm (left and right sides)

4. Extend the pinky to >90° angle with the rest of the hand (left and right sides)

5. Place both palms flat on the floor without flexing the knees

One of the biggest problems I see in today’s strength and conditioning world is that we assume all “big, strong” athletes are tight and need aggressive stretching. As an example, take a look at this high Beighton score in a 6-3, 240-pound athlete. We do very little static stretching with him – and absolutely none in the upper body.

If someone is really lax, nix the static stretching and instead spend more time on stabilization work. If they still feel like they need to “loosen up,” tell them to do some extra foam rolling. They’ll transiently reduce some of the stiffness they’re feeling, but they won’t be working through harmful end-range joint range-of-motion in the process.

Mistake #2. Substituting knee hyperextension for hip flexion in hamstrings stretches.

This comment piggybacks a little bit on mistake #1, as lax individuals (who probably shouldn’t be stretching their hamstrings, anyway) are the most likely to have problems with this. Because the hamstrings are two-joint muscles (knee and hip), folks will often allow the knee to “give” extra because they are subconsciously trying to avoid an uncomfortable stretch at the hip – or they simply aren’t paying attention. These are the same folks who have terrible hip hinges on toe touch tests, yet can touch their toes without a problem; they just go to knee hyperextension to make it happen. As an example, this particular athlete scores really high on the Beighton hypermobility score, and he can actually put his palms flat on the floor with little to no posterior weight shift (the wall blocks him).

How does he do it? Knee hyperextension.

We’d much rather get a good hip hinge without resorting to excessive joint range of motion at the knee. You get good at what you train, so if you’re always doing your static stretching in a bad position, you’re going to be more likely to wind up in knee hyperextension on the field – and that’s where ACL injuries occur.

Mistake #3: Not creating stiffness at adjacent joints.

In a previous post, I talked about why stiffness can be a good thing, in spite of the negative connotation of the word. Stiffness is a crucial part of keeping us healthy and enhancing athleticism. “Good” stiffness allows us to overpower “bad” stiffness that’s occurring in the wrong places, and it helps to transfer force as part of the kinetic chain. Static stretching can either be an opportunity to foster good stiffness or develop bad habits.

You see, we static stretch to transiently reduce stiffness (or true tissue shortness). However, if we don’t stabilize (stiffen up) adjacent joints, it defeats the purpose. Let me give you an example.

Let’s say that I want to stretch my hamstrings in the supine position with not just a neutral position (center), but also a bias toward internal rotation/adduction (left) and external rotation/abduction (right).

Now, let’s see what happens to these stretches if one doesn’t engage the lateral core to prevent the pelvis from rolling toward the direction of the stretch on the ones that go out to the sides.

Mistake #4: Irritating the medial aspect of the knee with 90/90 hip stretches.

Most folks are familiar with doing 90/90 hip stretches or cradle walks as a way to improve hip external rotation in a position of hip flexion. This is the position I commonly see people using at the point of maximal stretch:

The problem is that many folks crank excessively on the medial aspect of the knee by rotating the tibia (lower leg) instead of the femur (upper leg). This actually parallels what happens during a McMurray’s Test for medial meniscus pathology:

It’s a pretty safe bet that static stretching into a position that replicates a provocative test is never a good idea – and it’s one reason we use 90/90 stretches very sparingly. If you are going to use this stretch, however, I recommend that individuals grab the quadriceps on the stretching side to ensure that the majority of the pull into external rotation and flexion comes from the femur and not the tibia. The opposite hand is simply there to support the weight of the lower leg.

Mistake #5: Substituting valgus stress at the knee for hip adduction/internal rotation stretching.

It’s really important than folks have adequate hip internal rotation, as a loss of hip internal rotation has been correlated with low back pain, and it can certainly predispose individuals to hip and knee issues as well. The knee-to-knee stretch is a popular approach for maintaining and improving hip internal rotation, and it’s also my chosen method for demonstrating how incomplete my goatee was at the time of this picture.

As you can see from the picture, this position can also impose some valgus stress at the knees if it isn’t coached/cued properly. So, instead of thinking of letting the knees fall in, I tell athletes to actively internally rotate the femurs (upper leg). The stretch should occur at the hips, not the knees.

In folks with a history of medial knee issues, we won’t use this static stretch. Rather, we’ll use a kneeling glute stretch, which still gets a bit of stretch into adduction, which will still stretch several of the hip external rotators indirectly.

Lastly, keep in mind that the knee-to-knee isn’t a stretch most females will ever have to utilize because of their tendency toward a knock-knee posture (wider hips = greater Q-angle) at rest.

Mistake #6: Not monitoring neutral spine during hip stretching.

This point really works hand-in-hand with #3 from above, which talked about establishing stiffness at adjacent joints. Certainly, maintaining neutral spine falls under the category of “good stiffness,” but because it’s such a common mistake, it deserves attention of its own. When the hip flexes, you shouldn’t go through lumbar flexion. For this split-stance kneeling adductor stretch, notice the correct on the left and the incorrect on the right:

And, when it extends, you shouldn’t go through lumbar extension. Again, the correct is on the left, and incorrect (hyperextended) is on the right:

Mistake #7: Not monitoring neutral spine during standing stretches.

Again, this is another point that piggybacks off of establishing good stiffness, but I see a lot of people doing upper extremity stretches – overhead triceps, lats, pecs – in terrible spine posture. Perhaps the best example is the overhead triceps stretch with the lumbar spine in hyperextension, plus forward head posture further up.

Mistake #8: Stretching your lower back.

There may be times when a qualified manual therapist might want to do some mobilizations on your lower back. The rest of you really shouldn’t be stretching your spine out. Stretch your hips, and mobilize your thoracic spine (upper back), where it’s much safer for you to move. Focus on building up some core stability.

Mistake #9: Stretching your calves – and then wearing high heels the rest of the day.

There’s nothing wrong with the “stretching your calves” part; it’s the high heels part that makes me want to bang my head against the wall. Talk about a dog chasing its tail!

Mistake #10: Stretching a throwing shoulder into extension and/or external rotation (and creating valgus stress at the elbow in the process).

I devoted an entire video to this topic last week in my baseball-specific newsletter:

Mistake #11: Stretching through pain or neurological symptoms.

I honestly can’t think of a single reason why anyone should ever stretch oneself through pain. Sure, there may be times when physical therapists may push a post-operative joint through some uncomfortable ranges of motion, but that’s a trained professional making a educated decision. You stretching yourself through pain is just throwing a bunch of s**t on the wall to see what sticks. Don’t do it.

Sometimes, an indirect approach is better. As an example, there is research demonstrating that core stability exercises can transiently and chronically improve hip internal rotation – even without stretching the joint. If you’re hurting while stretching, see a qualified medical professional to help you devise a plan to work around the issue while reducing your symptoms.

On the topic of neurological symptoms, as an example, intervertebral disc issues with radicular symptoms into the legs may be exacerbated by stretching the hamstrings. Similar issues can come about if folks with thoracic outlet syndrome perform aggressive upper body stretching. If nerves aren’t gliding the way that they need to be, the last thing you want to do is yank on them.

Mistake #12: Not tightening the glutes during hip flexor stretches.

I’ve written previously at length about how anterior (front) hip irritation is often caused the head of the femur (ball) gliding forward in the acetabulum (socket) during hip extension. This femoral anterior glide syndrome (described in detail here), was originally introduced by physical therapist Shirley Sahrmann. Effectively, the hamstrings have a “gross” hip extension pull – meaning that they don’t have a whole lot of control over the head of the femur. Therefore, we need to have great gluteus maximus contribution to hip extension, as the glute max posteriorly pulls the femoral head back during hip extension so that the anterior hip capsule doesn’t get irritated.

What we don’t consider, however, is that if we stretch a hip into hip extension (osteokinematics), we also need that glute contribution to control the glide (arthrokinematics) of the femoral head. This is a definite parallel to what I described earlier with respect to stretching a throwing shoulder into extension or external rotation; you don’t just want to do it carelessly. As such, whenever you stretch the hip into extension, make sure that you tighten up the glute:

Mistake #13: Stretching into a bony block.

There are a lot of things that may limit range of motion at a joint. It could be muscular shortness/stiffness, capsular tightness, muscular bulk, swelling, or guarding due to injury. In many cases, though, it simply has to do with the congruency of the bones (or lack thereof) at a joint.

In the case of a “fresh” bone spur or loose body at the posterior aspect of the elbow, aggressively stretching into extension could easily provoke symptoms. Conversely, I’ve seen some elbows with flexion contractures that are a combination of bony blocks and subsequent tissue shortening and capsular tightening that can be stretched until the cows come home with no problem.

Each case is unique – but at the end of the day, remember that you’re better off being too tight than too loose. In other words, if you’re unsure about something, don’t stretch it.

Beyond just reactive changes like bone spurs and loose bodies, we also have folks who simply have different congenital or acquired bone structures. Many individuals have retroverted (externally rotated) or anteverted (internally rotated) femoral carrying angles. Those in retroversion will lack hip internal rotation no matter how much you stretch them, and those in anteversion aren’t going to be gaining external rotation no matter what you do. Trying to power through these bony blocks will likely create hip discomfort as well.

We also see retroversion as an adaptation in throwing shoulders, where bones “warp” to allow for more lay-back during the extreme cocking phase of throwing. This is why most throwers will have significantly less internal rotation on the throwing shoulder than on the non-throwing shoulder in-spite of the fact that they have symmetrical total motion (IR + ER) from side to side; they simply shift their arc.

Before you stretch, you better find out if it’s bone or soft tissue that is limiting you at end-range. If it’s bone, you’re better off leaving things alone.

Mistake #14: Putting the band behind your head during hamstrings stretching.

This one drives me bonkers. It screams “I know stretching isn’t hard to do, but I’m still too lazy to put any semblance of effort into doing it correctly.” Why create forward head posture and neck stress when stretching the hamstrings?

Mistake #15: Not monitoring your breathing.

Nowadays, I’d say that we do just as much “positional breathing drills” as we do actual stretches. The more I learn (particularly from the Postural Restoration Institute school of thought), the more I realize that breathing in specific positions can have a dramatic effect on reducing tissue stiffness. For instance, here is one that many of our right-handed pitchers do.

The left femur is internally rotated and adducted, the left rib flare is “tucked,” right thoracic rotation is encouraged, the lumbar spine is flat, and the right shoulder blade is fully upwardly rotated with a bit of upper trap activation. We cue the athlete to inhale through the nose without allowing the rib cage to “fly up,” and then encourage him to exhale fully, allowing the ribs to “come down.”

We stretch to reduce tone, not increase it – and most athletes are in a constant state of inhalation, which corresponds to a big anterior pelvic tilt and lordotic curve.

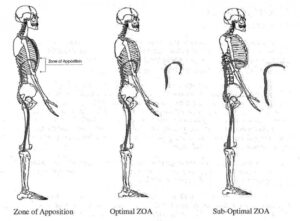

When the rib cage flies up like this, we lose our Zone of Apposition (ZOA), a term the PRI folks have coined to describe the region into which our diaphragm must expand to function.

Source: www.PosturalRestoration.com

In this extended posture, rather than effectively use their diaphragm, athletes will overuse supplemental respiratory muscles like lats, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, and pec minor – and these are all areas where we’re always trying to reduce tone.

Teaching athletes how to control their breathing during stretching – and paying particular attention to fully exhaling on each breath – goes a long way to help reduce sympathetic nervous system stimulation, get rid of unwanted tone in the wrong places, effective favorable changes to posture, and make the most of the stretches you’re prescribing. I think the folks in the yoga and Pilates worlds have done a good job of drawing attention to the importance of breathing, and we should appreciate that with respect to how static stretching and dynamic flexibility drills are implemented.

Conclusion

There are really only 15 mistakes that were right on the tip of my tongue – to the tune of 2,800 words! To reiterate, I have a lot of clients/athletes who do absolutely no static stretching, but that’s not to say that it can’t be of benefit to a good chunk of the population. Just remember that each body is unique, so no two static stretching programs should be alike in terms of exercise selection and coaching cues.

If you benefited from this article, please share it on social media, as this is a very misunderstood topic in the world of health and human performance. Thanks for your support!