Random Thoughts on Sports Performance Training – Installment 16

With all our Major League Baseball affiliated athletes having left for spring training, things are a bit quieter at Cressey Sports Performance.

![]()

At this time of year, I always like to look back and reflect on the offseason and some of the lessons we’ve learned. Invariably, it leads to a blog of random thoughts on sports performance training! Here are some things that are rattling around my head right now:

1. Just getting a baseball out of one’s hand improves shoulder function – even if an athlete doesn’t actually do any arm care or “corrective exercises.”

If you look at the glenohumeral joint (ball-and-socket of the shoulder), stability in a given situation is essentially just a function of how well the ball stayed in good congruency with the socket. This congruency is governed by a number of factors, most notably the active function of the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff. This is what good arm care work is all about.

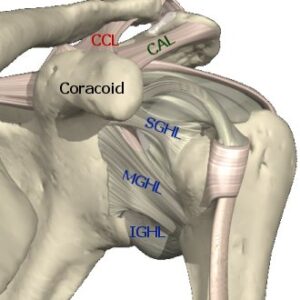

However, what many folks overlook is that there are both passive (ligamentous) and active (muscular) structures that dramatically influence this congruency. In the throwing shoulder, we’re talking predominantly about the inferior, middle, and superior glenohumeral ligaments and long head of the biceps tendon; collectively, the provide anterior (front) stability to the joint so that the ball doesn’t fly forward too far in the socket in this position:

These ligaments and biceps tendon are always working hard as superior (top) stabilizers of the joint at this point, especially in someone with a shoulder blade that doesn’t upwardly rotate effectively. By the end of a long season, these ligaments are a bit looser and the biceps tendon is often cranky. Good arm care exercises shifts the stress to active restraints (cuff and scapular stabilizers) that can protect these structures.

What often gets overlooked is the fact that simply resting from throwing will improve shoulder function in overhead athletes. When you avoid a “provocative” position and eliminate any possibility of pain, joint function is going to improve. And, ligaments that need to stiffen up are going to be able to do so and offer more passive stability.

This is a huge argument in favor of taking time off from throwing at the end of a season. It’s effectively “free recovery” and “free functional improvements.” Adding good arm care work on top of abstaining from throwing makes the results even better.

*Note: this isn’t just a shoulder thing; the ulnar collateral ligament at the elbow can regain some passive stability with time away from throwing as well.

2. Coaches need to find ways to be more efficient – and shut up more often.

Each year, we start up three intern classes at both the Florida and Massachusetts facilities. As such, we have an opportunity to interact with approximately 30 up-and-coming strength and conditioning coaches. Mentoring these folks is one of my favorite parts of my job – and it has taught me a lot about coaching over the years.

Most interns fall into one of two camps: they either coach too much (the “change the world” mentality) or too little (the “don’t want overstep my bounds” mentality). This is an observation – not a criticism – as we have all “been there” ourselves. I, personally, was an over-coacher back in my early strength and conditioning years.

The secret to long-term coaching success is to find a sweet spot in the middle. You have to say enough to create the desired change, but know when to keep quiet so as to not disrupt the fun and continuity of the training process. My experience has been that it’s easier to quickly improve the under-coacher, as most folks will develop a little spring in their step when it’s pointed out that they’re missing things. That adjustment usually puts them right where they need to be.

The over-coacher is a different story, though. It’s hard to shut off that “Type A” personality that usually leads someone in this direction. My suggestion to these individuals is always the same, though:

Don’t let the game speed up on you. Before you say anything, pause – even take a deep breath, if you need to – and then deliver a CLEAR, CONCISE, and FIRM cue. Try to deliver the important message in 25% as many words as you normally would.

The athletes don’t get overwhelmed, but just as importantly, the coach learns what the most efficient cues are. You might talk less, but you actually deliver more.

3. Use the “hands and head together” cue with rollouts and fallouts.

One of the biggest mistakes we’ll see with folks when they do stability ball rollouts is that the hands will move forward, but the hips will shoot back. This reduces the challenge to anterior (front) core stability, and can actually drive athletes into too much lumbar extension (lower back arching). By cueing “hand and hips move together,” you make sure they’re working in sync – and then you just have to coach the athlete to resist the impacts of gravity on the core.

You can apply this same coaching cue to TRX fallouts, too:

4. Ages 28-30 seems to be a “tipping point” on the crappy nutrition front.

I should preface this point by saying that there is absolutely nothing scientific about this statement; it’s just an observation I’ve made from several conversations with our pro guys over the winter. In other words, it’s purely anecdotal, but I’d add that I consider myself one of the “study” subjects.

We all know that many young athletes seem to be able to get away with absolutely anything on the nutrition front. We hear stories about pro athletes who eat fast food twice a day and still succeed at the highest levels in spite of their nutritional practices.

One thing I’ve noticed is that I hear a lot more observations about “I just didn’t feel good today,” “my shoulder is cranky,” or any of a host of other negative training reports in the days after a holiday. The pro baseball offseason includes Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s Eve/Day, and Valentine’s Day. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these observations almost always come from guys who are further along in their career – and as I noted, it’s something I’ve felt myself.

If you eat crap, you’re going to feel like crap.

Why does it seem to be more prevalent in older athletes? Surely, there are many possible explanations. More experienced athletes are usually more in-tune with their bodies than younger ones. Recovery is a bigger issue as well, so they might not have as much wiggle room with which to work as their younger counterparts. Older athletes also generally have more competing demands – namely kids, and the stress of competing at the highest levels – that might magnify the impacts of poor nutrition.

Above all, though, I think the issue is that many young athletes with poor nutritional practices have no idea what it’s like to actually feel good. They might throw 95mph or run a 40 under 4.5 seconds, but they don’t actually realize that their nutrition is so bad that they’re actually competing at 90-95% of their actual capacity for displaying and sustaining athleticism. It’s only later – once they’ve gotten on board with solid nutrition – that they have something against which they can compare the bad days.

Again, this is purely a matter of anecdotal observations, but as I’ve written before, everyone is invincible until they’re not. As coaches, it’s our job to make athletes realize at a younger age the profound difference solid nutrition can make. We can’t just sit around and insist that they’ll come around when they’re ready, as that “revelation” might be too late for many of them.

Speaking of nutrition, today is the last day to get the early-bird registration discount on Brian St. Pierre’s nutrition seminar at Cressey Sports Performance – MA on April 10. Brian is the director of performance nutrition for Precision Nutrition, and is sure to deliver a fantastic learning experience. You can learn more HERE.