|

Q: I noticed that you include reverse crunches in Maximum Strength, but not standard crunches. Why is it acceptable to have lumbar flexion during a reverse crunch, but not during a standard crunch?

A: This is a great question - and there are a few components to my response.

First, we use reverse crunches in moderation and only in our athletes who are healthy and those who have extension-based back issues (i.e., more pain in standing than sitting, tight hip flexors, anterior pelvic tilt, dormant glutes). We wouldn't use it in folks who have or have had flexion-based back issues (generally, this equates to disc problems and more pain in sitting).

Second, keep in mind that this is unloaded lumbar flexion; we wouldn't add compression to the mix.

Third, and most specific to your question, reverse crunches target the posterior fibers of the external oblique more. Given the points of insertion of these fibers, you can address anterior pelvic tilt without affecting the position of the rib cage.

Regular crunches shorten the rectus abdominus. While this can help with addressing anterior pelvic tilt, you also have to realize that shortening the rectus abdominus will depress the rib cage and pull people into a more kyphotic position. This is not a good thing for shoulder, upper back, or neck health.

So, in a nutshell, if we are going to have any sort of lumbar flexion in our training, it has to be a) unloaded, b) in the right population, c) implemented in lower volumes, and d) offering us something that addresses another more pressing issue (e.g., anterior pelvic tilt).

Combat Core is an exhaustive resource on high-performance core training that I'd encourage you to check out as well.

So, in a nutshell, if we are going to have any sort of lumbar flexion in our training, it has to be a) unloaded, b) in the right population, c) implemented in lower volumes, and d) offering us something that addresses another more pressing issue (e.g., anterior pelvic tilt).

Combat Core is an exhaustive resource on high-performance core training that I'd encourage you to check out as well.

|

| Read more |

|

This morning, my girlfriend turned on Regis and Kelly. Now, before you start giving me a hard time, I’ll make it known that a) it was her choice and b) I was checking my emails, and my computer happens to be in the neighborhood of my television.

My attention shifted from emails to the TV when I saw that they were featuring a transformation contest where a bunch of ordinary weekend warriors went to different personal trainers to get “toned” (I knew I was in for it when I heard that word).

In the minutes that followed, I heard the word “core” mentioned approximately 487 times as trainers put clients through all sorts of stuff:

1. interval jogging on a treadmill (nearly made me vomit in my mouth)

2. playing basketball (You can charge for that? I would have gone with dodgeball so that I could throw stuff at my trainer for ripping me off.)

3. Curls while standing on a BOSU ball in a pair of Nike Shox (yes, you can actually find a way to make unstable surface training MORE injurious by exaggerating pronation even more)

Incidentally, this third trainer was featured with some hardcore Kelly Clarkson blaring in the background. I not only got dumber (and angry) by watching this segment; I also realized that if I ever go nuts and decide to write my suicide note, you’ll hear “SINCE YOU’VE BEEN GONE!!!!” blaring in the background as I sob over my pen and paper.

Normally, my reaction wouldn’t have been so pronounced, but after this weekend, I was all about REAL “core stability.” You see, I got to catch up with my buddy, Jim Smith (of Diesel Crew fame), while in Pittsburgh to give a seminar. “Smitty” and Jedd Johnson gave an awesome presentation outlining their innovative and effective methods on everything from sled dragging to grip work – and most specific to the discussion at hand, they both raved about how much they love Kelly Clarkson! Plus, they’re HUGE Regis and Kelly fans.

Okay, so that last little bit wasn’t entirely accurate; I’m pretty sure that these guys would have Hatebreed or some other angry, belligerent, “my-mother-didn’t love me” music blaring in the background when they finally get their moment in the spotlight on Regis and Kelly. Anyway, they DO know a ton about non-traditional means of training “core stability.”

In addition to watching a great presentation, on the plane ride home, I finally got a chance to read through Smitty’s new e-book, Combat Core: Advanced Torso Training for Explosive Strength and Power. To say that I was impressed would be the understatement of the year.

You see, I spend a ton of money each year on seminars, books, DVDs, etc. – and if I can take away even one little thing from each of them, I’m thrilled. In many cases, it’s “same-old, same-old.” Smitty has quickly built a reputation for overdelivering, and this resource was no exception. In the 133 pages of photos and descriptions of loads of exercises you’ve surely never seen, I found:

-13 sweet modifications to exercises I’m already doing

-16 completely new exercises I can’t wait to incorporate to my own training and that of my athletes

-seemingly countless “why didn’t I think of that?” moments.

So, to put it bluntly, I think it’s an awesome read – and well worth every penny, especially when you factor in all the bonuses he’s incorporated (including lifetime updates to keep you up to speed on his latest bits of insanity). If you’re interested in some effective, fun, innovative ways to enhance TRUE core stability, definitely check it out:

Combat Core: Advanced Torso Training for Explosive Strength and Power |

| Read more |

|

Mike Robertson flew up from Indianapolis to check out a seminar up here in Boston this past weekend. We really enjoyed watching Kevin Wilk, Bob Mangine, and Mark Comerford, three fantastic rehabilitation specialists. Additionally, I enjoyed catching up with Mike just as much, as he’s a wealth of information, particularly with respect to the knees. From just talking with Mike this weekend, I picked up some really good stuff – in addition to the entire day the presenters spent on the knee this weekend.

With that in mind, on Sunday, I wrote down five things that caught my attention this weekend. Then, I handed them to Mike and asked him to elaborate on them on his laptop on the plane ride home for a “guest spot” in my newsletter. Here’s what you’ve got:

5 Keys to Bulletproofing Your Knees

1. VMO specific work is currently poo-poo in the strength and conditioning industry. While I agree that we need to focus on strengthening the hip abductors/external rotators (especially glute max and posterior glute med), current literature leads us to believe that there’s more to the VMO than we might have expected.

Several studies in the past two years have indicated that there is a definite change in fiber pennation between the vastus medialis longus (VML) and the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO). Beyond that, while your other quad muscles like rectus femoris and vastus lateralis only have one motor point, the entire vastus medialis actually has THREE motor points!

We may not totally understand the VMO yet, but I’m not willing to write off its importance with regards to knee health.

2. When looking at the body as a functional unit, we can’t overlook the core with regards to knee health. More specifically, we know the rectus abdominus and external obliques work to keep us in pelvic neutral and out of anterior pelvic tilt. Lack of strength in these core muscles increases anterior pelvic tilt, which drives internal rotation of the hip and valgus of the knee. Getting and keeping these muscles strong could go a long way to preventing knee injuries, especially in female athletes.

3. Are accelerated ACL rehab programs what we need? I’m not so sure, and I think making young athletes follow the accelerated programs the pros use may do more harm than good. Unlike the pros that are getting paid to play, we need to focus on the long-term outcomes of our young athletes, not simply getting them back on the field ASAP.

Many have done an excellent job of rehabbing patients and getting them back on the field quickly, and quantifying strength and power production/absorption is critical. Many of the leading PT’s and orthos, however, are moving back to a slightly more conservative approach to allow the graft itself more time to heal. The properties of a tendon graft slowly take on the properties of a ligament over time; this is called ligamentization. However, ligamentous changes can still be seen as late as 12-18 months post-surgery.

[Note from EC: so, if you have a patellar tendon graft for a new ACL, you might not really have what you want until 1-1.5 years post-surgery. Tendons and ligaments have different qualities.]

4. To piggy-back on the previous point, another factor that isn’t examined as often as it should is long-term outcomes of ACL rehabbed clients. Sure it’s great to get them back on the field in 6, 9 or 12 months, but what are the long-term ramifications?

We know that females who have suffered ACL tears are much more likely to develop early osteoarthritis. If we can improve long-term outcomes by keeping them out a little longer, isn’t that worth it? As a PT or strength coach, it’s our job to help clients/athletes make the best decision for their long-term health, especially if they are too young to understand the long-term repercussions of their decision.

5. When an athlete tears their ACL, proprioceptive deficits are seen as quickly as 24 hours post-injury. What’s really intriguing, however, is that we often see this same deficit carried over to the healthy knee as well! Even after reconstruction this deficit can be seen for up to six years.

To counteract this, don’t forget to include basic proprioceptive training (barefoot warm-ups, single-leg stance work, etc.), and train that “off” leg in the interim.

For more tips, tricks, and programming recommendations on knees, check out Mike Robertson’s Bulletproof Knees manual. It’s by far the best resource I’ve seen on preventing and addressing knee pain.

New Blog Content

Just One Missing Piece

Training Around Elbow Issues in Overhead Athletes

Random Thursday Thoughts

Sturdy Shoulders: Big Bench

All the Best,

EC

PS - For those who missed it last week, be sure to check out my new e-book, The Truth About Unstable Surface Training, at www.UnstableSurfaceTraining.com. |

| Read more |

|

Last week, I was fortunate enough to get a free copy of Mike Robertson and Bill Hartman’s 2008 Indianapolis Performance Enhancement Seminar DVD Set. To be honest, the word “fortunate” doesn’t even begin to do the product justice; it was the best industry product I’ve watched all year.

The DVD set is broken up into six separate presentations:

1. Introduction and 21st Century Core Training

2. Creating a More Effective Assessment

3. Optimizing Upper Extremity Biomechanics

4. Building Bulletproof Knees

5. Selecting the Optimal Method for Effective Flexibility Training

6. Program Design and Conclusion

To be honest, I’ve already seen Mike Robertson deliver the presentations on DVDs 1 and 4 a few times during seminars at which we’ve both presented, so more of my focus in this review will be on Bill’s presentations because they were more “new” to me. That said, I can tell you that each time I’ve seen Mike deliver there presentations, he’s really impressed the audience and put them in a position to view training from a new (and better) paradigm, debunking old myths along the way. A lot of the principles in his core training presentation mirror what we do with our clients – and particularly with those involved in rotational sports.

Bill’s presentation on assessments is excellent. I think I liked it the most because it really demonstrated Bill’s versatility in that he knows how to assess both on the clinical (physical therapy) and asymptomatic (ordinary client/athlete) sides of the things. A few quick notes from Bill’s presentation that I really liked:

a. Roughly 40% of athletes have a leg length discrepancy – but that’s not to say that 40% of athletes are injured or even symptomatic. As such, we need to understand that some asymmetry is normal in many cases – and determining what is an acceptable amount of asymmetry is an important task. As an example, in my daily work, a throwing shoulder internal rotation deficit (relative to the non-throwing shoulder) of 15 degrees or less is acceptable – but if a guy goes over 15°, he really needs to buckle down on his flexibility work and cut back on throwing temporarily. If he is 17-18° or more, he shouldn’t be throwing – period.

b. It’s important to consider not only a client/patient/athlete looks like on a “regular” test, but also under conditions of fatigue. There’s a reason athletes get hurt more later in games: fatigue changes movement efficiency and safety! This is why many tests should include several reps – and we should always be looking to evaluate players “on the fly” under conditions of fatigue.

c. Bill made a great point on “functional training” during this presentation as well – and outlined the importance difference between kinetics (incorporates forces) and kinematics (movement independent of forces). Most functional training zealots only look at kinematics, and in the process, ignore the amount of forces in a dynamic activity. For example, being able to execute a body weight lateral lunge with good technique doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be “equipped” to handle change-of-direction challenges at game speed. In reality, this force consideration is one reason why there are times that bilateral exercise is actually more function than unilateral movements!

d. Bill also outlined a multi-faceted scoring system he uses to evaluate athletes in the context of their sports. It’s definitely a useful system for those who want a quantifiable scheme through which to score athletes on overall strength, speed, and flexibility qualities to determine areas that warrant prioritization.

DVD #3 is an excellent look at preventing and correcting shoulder problems – and in terms of quality, this presentation with Mike is right on par with their excellent Inside-Out DVD. Mike goes into depth on what causes most shoulder problems and how we can work backward from pathology to see what movement deficiency – particularly scapular downward rotation syndrome – caused the problem. There is a great focus on lower trapezius and serratus anterior strengthening exercises and appropriate flexibility drills for the pec minor, levator scapulae, and thoracic spine – as well as a focus on the effects of hip immobility and rectus abdominus length on upper body function.

To be honest, I think that DVD #4 alone is worth far more than the price of the entire set. It actually came at an ideal time for me, as I’m preparing our off-season training templates for our pro baseball guys – and flexibility training is a huge component of this. Whenever I see something and it really gets me thinking about what I’m doing, I know it’s great. Bill’s short vs. stiff discussion really did that for me.

Bill does far more justice to the discussion than I can, but the basic gist of the topic is that the word “tight” doesn’t tell us much at all. A short muscle actually has lost sarcomeres because it’s been in a shortened state for an extended period of time; this would be consistent with someone who had been immobilized post-surgery or a guy who has just spent way too long at a computer. These situations mandate some longer duration static stretching to really get after the plastic portion of connective tissue – and this can be uncomfortable, but highly effective.

Conversely, a stiff muscle is one that can be relatively easily lengthened acutely as long as you stabilize the less stiff segment. An example would be to stabilize the scapula when stretching someone into humeral internal or external rotation. If the scapular stabilizers are weak (i.e., not stiff), manually fixing the scapula allows us to effectively stretch the muscles acting at the humeral head. If we don’t stabilize the less-stiff joint, folks will just substitute range of motion there instead of where we actually want to create it. In situations like this, in addition to good soft tissue work, Bill recommends 30s static stretches for up to four rounds (this is not to be performed pre-exercise, though; that’s the ideal time for dynamic flexibility drills.

DVD #5 is where Mike is at his best: talking knees. This is a great presentation not only because of the quality of his information, but also because of his frame of reference; Mike has overcome some pretty significant knee issues, including a surgery to repair a torn meniscus. Mike details the role of ankle and hip restrictions in knee issues, covers the VMO isolation mindset, and outlines some of the research surrounding resistance training and rehabilitation of knee injuries in light of some of the myths that are abundant in the weight-training world.

DVD #6 brings all these ideas together with respect to program design.

I should also mention that each DVD also includes the audience Q&A, which is a nice bonus to the presentations themselves. The production quality is excellent, with “back-and-forths” between the slideshow and presenters themselves. Bill and Mike include several video demonstrations in their presentations to break up the talking and help out the visual learners in the crowd, too.

All in all, this is a fantastic DVD set that encompasses much more than I could ever review here. In fact, if it’s any indicator of how great I think it is, I’m actually going to have all our staff members watch it. If you train athletes or clients, definitely get it. Or, if you’re just someone who wants to know how to keep knees, shoulders, and lower backs healthy while optimizing flexibility, it’s worth every penny. You can find out more at the Indianapolis Performance Enhancement Seminar website.

New Blog Content

Maximum Strength: The Personal Trainer’s Perspective

Random Friday Thoughts: 7/25/08

Training around Knee Pain

Willing and Abele

All the Best,

EC

|

| Read more |

|

On Monday night, Josh Hamilton put on an amazing show with 28 homeruns in the first round of the MLB Homerun Derby. While he went on to lose to Justin Morneau in the finals of the contest, Hamilton did smash four 500+ ft. shots - and stole the hearts of a lot of New York fans. It's an incredible story; Hamilton has bounced back from eight trips to rehabilitation for drugs and alcohol to get to where he is today.

Geek that I am, though, I spent much of the time focusing on the incredible hip rotation and power these guys display on every swing. According to previous research, the rotational position of the lead leg changes a ton from foot off to ball contact. After hitting a maximal external rotation of 28° during the foot off “coiling” that takes place, those hips go through some violent internal rotation as the front leg gets stiff to serve as a “block” over which crazy rotational velocities are applied.

How crazy are we talking? How about 714°/s at the hips? This research on minor leaguers also showed that stride length averaged 85cm - or roughly 380% of hip width. So, you need some pretty crazy abduction and internal rotation range-of-motion (ROM) to stay healthy. And, of course, you need some awesome deceleration strength – and plenty of ROM in which to apply it – to finish like this.

Meanwhile, players are dealing with a maximum shoulder and arm segment rotational velocities of 937°/s and 1160°/s, respectively. All of this happens within a matter of 0.57 seconds. Yes, about a half a second.

These numbers in themselves are pretty astounding – and probably rivaled only by the crazy stuff that pitchers encounter on each throw. All these athletes face comparable demands, though, in the sense that these motions take a tremendous timing to sequence optimally. In particular, in both the hitting and pitching motions, the hip segment begins counterclockwise (forward) movement before the shoulder segment (which is still in the cocking/coiling phase). Check out this photo of Tim Hudson (more on this later):

Many of you have probably heard about a “new” injury in major league baseball – oblique strains – which have left a lot of people looking for answers. In fact, the USA Today published a great article on this exact topic earlier this season. Guys like Hudson, Chris Young, Manny Ramirez, Albert Pujols, Chipper Jones and Carlos Beltran (among others) have dealt with this painful injury in recent years. You know the best line in this entire article? With respect to Hudson:

“After the 2005 season, he stopped doing core work and hasn't had a problem. Could that be the solution?”

I happen to agree with the mindset that some core work actually contributes to the dysfunction – and the answer (to me, at least) rests with where the injury is occurring: “always on the opposite side of their throwing arm and often with the muscle detaching from the 11th rib.” If I’m a right-handed pitcher (or hitter) and my left hip is already going into counter-clockwise movement as my upper body is still cocking/coiling in clockwise motion – both with some crazy rotational velocities – it makes sense that the area that is stretched the most is going to be affected if I’m lacking in ROM at the hips or thoracic spine.

I touched on the need for hip rotation ROM, but the thoracic spine component ties right into the “core work” issue. Think about it this way: if I do thousands of crunches and/or sit-ups over the course of my career – and the attachment points of the rectus abdominus (“abs”) are on the rib cage and pelvis – won’t I just be pulling that rib cage down with chronic shortening of the rectus, thus reducing my thoracic spine ROM in the process?

Go take another look at the picture of Tim Hudson above. If he lacks thoracic spine ROM, he’s either going to jack his lower back into lumbar hyperextension and rotation as he tries to “lay back” during the late cocking phase, or he’s just going to strain an oblique. It’s going to be even worse if he has poor hip mobility and poor rotary stability – or the ability to resist rotation where you don’t want it.

Now, I’m going to take another bold statement – but first some quick background information:

1. Approximately 50-55% of pitching velocity comes from the lower extremity.

2. Upper extremity EMG activity during the baseball swing is nothing compared to what goes on in the lower body. In fact, Shaffer et al. commented, “The relatively low level of activity in the four scapulohumeral muscles tested indicated that emphasis should be placed on the trunk and hip muscles for a batter's strengthening program.”

So, the legs are really important; that 714°/s at the hips has to come from somewhere. And, more importantly, it’s my firm belief that it has to stay within a reasonable range of the shoulder and arm segment rotational velocities of 937°/s and 1160°/s (respectively). So, what happens when we give a professional baseball player a foo-foo training program that does little to build or even maintain lower-body strength and power? And, what happens when we have that player run miles at a time to “build up leg strength?” How many marathoners do you know who throw 95mph and need those kind of rotational velocities or ranges of motion? Apparently, bigger contracts equate to weaker, tighter legs…

Meanwhile, guys receive elaborate throwing programs to condition their arms – and they obviously never miss an upper-body day (also known as a “beach workout"). However, the lower-body is never brought up to snuff – and it lags off even more in-season when lifting frequency is lower and guys do all sorts of running to “flush their muscles.” The end result is that the difference between 714°/s (hips) and 937°/s and 1160°/s (shoulders and arms) gets bigger and bigger. Guys also lose lead-leg hip internal rotation over the course of the season if they aren’t diligent with their hip mobility work.

So, in my opinion, here’s what we need to do avoid these issues:

1. Optimize hip mobility – particularly with respect to hip internal rotation and extension. It is also extremely important to realize the effect that poor ankle mobility has on hip mobility; you need to have both, so don’t just stretch your hip muscles and then walk around in giant high-tops with big heel-lifts all day.

2. Improve thoracic spine range of motion into extension and rotation.

3. Get rid of the conventional “ab training/core work” and any yoga or stretching positions that involve lumbar rotation or hyperextension and instead focus exclusively on optimizing rotary stability and the ability to isometrically resist lumbar hyperextension.

4. Get guys strong in the lower body, not just the upper body.

5. Don’t overlook the importance of reactive work both in the lower and upper-body. I’ve read estimates that approximately 25-30% of velocity comes from elastic energy. So, sprint, jump, and throw the medicine balls.

Sign-up Today for our FREE Baseball Newsletter and Receive a 47-Minute Presentation on Individualizing the Management of Overhead Athletes!

|

| Read more |

|

| Fantasy Day at Fenway Park

I’ll be making my Fenway Park debut on Saturday. I know it’s hard to believe, but it won’t be for my catching abilities, base-stealing prowess, or 95-mph two-seam fastball. Rather, I’ll be speaking on a panel at the annual Fenway Park Fantasy Day to benefit The Jimmy Fund. And, if people don’t give a hoot about listening to me, they’ve got a skills zone with batting cages, a fast-pitch challenge, and accuracy challenge on top of loads of contests and tours. I’ll be sure to snap some photos for you.

This is an absolutely great cause, and while I know most of you won’t be in attendance, I’d highly encourage you to support the cause with a donation to the Jimmy Fund. What they are doing is something very special, and I’m honored to be a part of it.

Subscriber Only Q&A

Q: One quick question. As a trainer, I'm sure you've come across certain clients who have a problem with their thoracic spine (mild hump) and need to work on mobilizing this region. Other than foam rollers, are there any other techniques or methods that can be used? Maybe there's a book or video out there I could purchase that gives me a better understanding of how to implement some new methods?

A: Thanks for the email. It really depends on whether you're dealing with someone who just has an accentuated kyphotic curve or someone who actually has some sort of clinical pathology (e.g. osteoporosis, ankylosing spondylitis, Cushing’s Syndrome) that's causing the "hump." In the latter case, you obviously need to be very careful with exercise modalities and leave the “correction” to those qualified to deal with the pathologies in question.

In the former case, however, there’s quite a bit that you can do. You mentioned using a foam roller as a “prop” around which you can do thoracic extensions:

Thoracic Extensions on Foam Roller

While some people think that tractioning the thoracic spine in this position is a bad idea, I don’t really agree. We’ve used the movement with great success and absolutely zero negative feedback or outcomes.

That said, I’m a firm believer that the overwhelming majority of thoracic spine mobilizations you do should integrate extension with rotation. We don’t move straight-ahead very much in the real-world, so the rotational t-spine mobility is equally important. Mike Robertson and Bill Hartman do an awesome job of outlining several exercises along these lines in their Inside-Out DVD; I absolutely love it.

With most of these exercises, you’re using motion of the humerus to drive scapular movement and, in turn, thoracic spine movement.

The importance of t-spine rotation again rang true earlier this week when I had lunch with Neil Rampe, director of corrective exercise and manual therapy for the Arizona Diamondbacks. Neil is a very skilled and intuitive manual therapist, and he had studied extensively (and observed) the effect of respiration. He made some great points about how we can’t get too caught up in symmetry. Neil noted that we’ve got a heart in the upper left quadrant, and a liver in the lower right. The left lung has two lobes, and the right lung has three – and there’s some evidence to suggest that folks can usually fill their left lung easier than their right. The right diaphragm is bigger than the left –and it can use the liver for “leverage.” The end result is that the right rib winds up with a subtle internally rotated position, which in turns affects t-spine and scapular positioning. Needless to say, Neil is a smart dude – and once I got over how stupid I felt – I started scribbling notes. I’m going to be looking a lot more at breathing patterns as a result of this lunch.

Additionally, it’s very important to look at the effects of hypomobility and hypermobility elsewhere on thoracic spine posture. If you’re stuck in anterior pelvic tilt with a lordotic spine, your t-spine will have to compensate by rounding in order to keep you erect. And, if you’ve shortened your pecs and pulled the scapulae into anterior tilt and protraction, you’ll have a t-spine that’s been pulled into flexion. Or, if you’ve done thousands and thousands of crunches, chances are that you’ve shortened your rectus abdominus so much that your rib cage is depressed to the point of pulling you into a kyphotic position.

On the hypermobility front, poor rotary stability at the lumbar spine can lead to excessive movement at a region of the spine that really isn’t designed to move. It’s one reason why I like Jim Smith’s Combat Core product so much; he really emphasize rotary stability with a lot of his exercises. Lock up the lumbar spine a bit, and you’ll get more bang for your buck on the t-spine mobilizations.

As valuable as all the t-spine extension and rotation drills can be, they are – when it really comes down to it – just mobility drills. And, to me, mobility drills yield transient effects that must be sustained and complemented by appropriate strength and endurance of surrounding musculature. Above all else, strength of the appropriate scapular retractors (lower and middle trapezius) is important. You can be very strong in horizontal pulling – but have terrible posture and shoulder pain – if you don’t row correctly.

Not being cognizant of head and neck position can lead to a faulty neck pattern:

Cervical hyperextension (Chin Protrusion) Pattern

Here, little to no scapular retraction takes place. And, whatever work is done by the scapular retractors comes from the upper traps and rhomboids – not what we want to hit.

Then, every gym has this guy. He just uses his hip and lumbar extensors to exaggerate his lordotic posture and avoid using his scapular retractors at all costs.

Another more common, but subtle technical flaw is the humeral extension with scapular elevation. Basically, by leaning back a bit more, an individual can substitute humeral extension for much of the scapular retraction that takes place – so basically, the lats and upper traps are doing all the work. This can be particularly stressful on the anterior shoulder capsule in someone with a scapula that sits in anterior tilt because of restrictions on pec minor, coracobrachialis, or short head of the biceps. Here is what that issue looks like when someone is upright like they should be. A good seated row would like like this last one – but with the shoulder blades pulled back AND down. We go over a lot of common flaws like these in our Building the Efficient Athlete DVD series.

Finally, don’t overlook the role that soft tissue quality plays with all of this. Any muscle – pec minor, coracobrachialis, short head of the biceps – that anteriorly tilts the scapulae can lead to these posture issues. Likewise, levator scapulae, scalenes, subclavius, and some of the big muscles like pec major, lats, and teres major can play into the problem as well. I’ve always looked at soft tissue work as the gateway to corrective exercise; it opens things up so that you can get more out of your mobility/activation/resistance exercise.

Hopefully, this gives you some direction.

All the Best,

EC

Sign-up Today for our FREE Baseball Newsletter and Receive a Copy of the Exact Stretches

used by Cressey Performance Pitchers after they Throw!

|

| Read more |

|

Random Thoughts from Todd Hamer

Todd Hamer is one of the most high-energy coaches I've ever encountered. However, unlike many coaches who attempt to use their energy to make up for a lack of knowledge and experience, Todd is a guy who really knows his stuff and understands how to coach. He really cares about his athletes and knows how to speak their language. Enjoy.

1. Watch your athlete’s feet! When an athlete is squatting, all of the force they are creating is being transferred through the feet. When your athlete begins the descent, do their feet stay flat on the ground? When they get to the bottom of their squat, do their shoes roll in or out? Or, can you see the weight shift forward? I have noticed that even when a squat looks good, if you really look at what the feet are doing, you can follow the chain to where the problem is and then fix that.

2. I was put on this earth to kill the word “core.” Every day, someone says to me, “my core is weak.” The reason that I am here to kill this word is because it means nothing. Define the core? When someone says their core is weak, to me it means they are weak. We have been so overexposed to the “core” that we have forgotten how to get stronger. It has been shown time and time again that all the muscles that people call the “core” are worked in a squat, clean, overhead squat and many other multi-joint movements. So get away from the core and get strong. I promise you can get a six pack. For more information, check out Jim Smith's Combat Core Manual.

3. Train more odd lifts. I (like many others) was to dogmatic in my approach to training athletes. People like DieselCrew.com and EliteFTS.com have helped me think more about how I am training my athletes. Why do we use barbells, dumbbells, kettlebells, sandbags ect? Why not trees and stones. It is important to get your athletes off the platform and away from the known and into the unknown. Sports are chaotic events; do not be afraid of some chaos in your training.

4. 90% of athletes overthink. What is the training age of your athletes? This is a question that you should ask yourself about every one of the people you train. The younger the training age, the less advanced the program should be. Most athletes want the newest craziest exercise and program. The problem is that most athletes just need to get stronger and more mobile. This can be accomplished with just working hard and sticking to the basics. Most of the time if an athlete’s squat form improves, then his mobility will improve along with his strength levels. Quit looking for the Holy Grail of training and start training.

5. Extend your network. Your network is everyone to whom you speak; make it larger. I have been lucky to be able to learn from and share ideas with hundreds of strength coaches, personal trainers, doctors, rehab specialists, and many other professionals. Each of these people have taught me something new about what I do. This is true for both business and personal facets of my life. I often hear other strength coaches say they will not listen to someone because they don’t work with athletes or they do not know what I do. So what? We must bring people in this field together if we ever want our field to grow.

About Todd Hamer

Todd Hamer has been working in the strength and conditioning field for seven years and has held positions at Marist College, the Citadel, Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania State University, and George Mason. He is now the head strength and conditioning coach at Robert Morris University. Todd has also worked as a personal trainer and consultant in several different facilities throughout his career. In his spare time, Todd is a competitive powerlifter with best lifts of a 545 lb squat, a 375 lb bench, and a 500 lb deadlift. A native of Pittsburgh, PA, he received his bachelor's of science degree in exercise science from Penn State in 1999 and his master's of science degree from the Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia in August 2002.

Until next time, train hard and have fun!

All the Best,

EC

|

| Read more |

|

Q&A rant that deserves a newsletter of its own...

Q: I have received a golf fitness program designed specifically for my injury history. This program came from the <Insert Noteworthy Golf Trainer’s Name Here>. I have concerns about this program.

Some of the exercises I am concerned about involve:

1. mimicking my golf swing on an unstable surface

2. performing one legged golf stance with my eyes closed

3. hollow my stomach for 30 second holds

4. upright rows

Correct me if I'm wrong but your advice on various T-Nation articles and your #6 Newsletter go against these practices. Should I look elsewhere for my golf fitness program?

A: Where do I even begin? That's simply atrocious!

I've "fixed" a lot of golfers and trained some to high levels, and we've never done any of that namby-pamby junk. In a nutshell...

1. I did my Master's thesis on unstable surface training, and it will be featured in the August issue of the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. Let’s just say that if the ground ever moves on YOU instead of you moving on the ground, you have bigger things to worry about than your golf conditioning; you’re in the middle of an earthquake!

2. There is considerable anecdotal evidence to support the assertion that attempting to replicate sporting tasks on unstable surfaces actually IMPAIRS the learning of the actual skill (think of competing motor learning demands). In a technical sport like golf, this is absolutely unacceptable.

3. Eyes closed, fine - but first show me that you can be stable with your eyes open! Most golfers are so hopelessly deconditioned that they can’t even brush their teeth on one foot (sadly, I’m not joking).

4. Abdominal hollowing is "five years ago" and has been completely debunked. Whoever wrote this program (or copied and pasted it from when they gave it to 5,000 other people) ought to read some of Stuart McGill's work - and actually start to train so that he/she gets a frame of reference.

I’m sorry to say that you got ripped off. The fact of the matter is the overwhelming majority of golfers are either too lazy to condition, or too scared that it’ll mess up their swing mechanics (might be the silliest assumption in the world of sports). So, said “Performance Institute” (and I use the word “performance” very loosely) puts out programs that won’t intimidate the Average Joe or his 80-year-old recreational golfer grandmother. For the record, Gram, I would never let you do this program, either (or Gramp, for that matter). On a semi-related note, Happy 85th Birthday, Gramp!

In short, I’m a firm believer in building the athlete first and the golfer later – and many golfers are so unathletic and untrained that it isn’t even funny. Do your mobility/activation to improve your efficiency, and then apply that efficiency and stability throughout a full range of motion to a solid strength training program that develops reactive ability, rate of force development, maximal strength, and speed-strength. Leave the unstable surface training, Body Blade frolicking, and four-exercise 3x10 band circuits for the suckers in the crowd.

I’m sorry to say that you got ripped off. The fact of the matter is the overwhelming majority of golfers are either too lazy to condition, or too scared that it’ll mess up their swing mechanics (might be the silliest assumption in the world of sports). So, said “Performance Institute” (and I use the word “performance” very loosely) puts out programs that won’t intimidate the Average Joe or his 80-year-old recreational golfer grandmother. For the record, Gram, I would never let you do this program, either (or Gramp, for that matter). On a semi-related note, Happy 85th Birthday, Gramp!

In short, I’m a firm believer in building the athlete first and the golfer later – and many golfers are so unathletic and untrained that it isn’t even funny. Do your mobility/activation to improve your efficiency, and then apply that efficiency and stability throughout a full range of motion to a solid strength training program that develops reactive ability, rate of force development, maximal strength, and speed-strength. Leave the unstable surface training, Body Blade frolicking, and four-exercise 3x10 band circuits for the suckers in the crowd.

Yours Cynically,

EC

Yours Cynically,

EC |

| Read more |

|

|

The “Great Eight” Reasons for Basketball Mobility Training

By: Eric Cressey

When it really comes down to it, regardless of the sport in question, the efficient athlete will always have the potential to be the best player on the court, field, ice, or track. Ultimately, knowledge of the game and technical prowess will help to separate the mediocre from the great, but that is not to say that physical abilities do not play a tremendously influential role on one’s success. Show me an athlete who moves efficiently, and I’ll guarantee that he or she has far more physical development “upside” than his or her non-efficient counterparts.

This “upside” can simply be referred to as “trainability;” I can more rapidly increase strength, speed, agility, and muscle mass in an athlete with everything in line than I can with an athlete who has some sort of imbalance. That’s not to say that the latter athlete cannot improve, though; it’s just to say that this athlete would be wise to prioritize eliminating the inefficiencies to prevent injury and make subsequent training more effective. Unfortunately, most athletes fall into the latter group. Fortunately, though, with appropriate corrective training, these inefficiencies can be corrected, and you can take your game to an all-new level. Mobility work is one example of the corrective training you’ll need to get the job done.

What’s the Difference Between Mobility and Flexibility?

This is an important differentiation to make; very few people understand the difference – and it is a big one. Flexibility merely refers to range of motion – and, more specifically, passive range of motion as achieved by static stretching. Don’t get me wrong; static stretching has its place, but it won’t take your athleticism to the next level like mobility training will.

The main problem with pure flexibility is that it does not imply stability nor readiness for dynamic tasks – basketball included. When we move, we need to have something called “mobile-stability.” This basically means that there’s really no use in being able to get to a given range of motion if you can’t stabilize yourself in that position. Believe it or not, excessive passive flexibility without mobility (or dynamic flexibility, as it’s been called) will actually increase the risk of injury! And, even more applicable to the discussion at hand, passive flexibility just doesn’t carry over well to dynamic tasks; just because you do well on the old sit-and-reach test doesn’t mean that you’ll be prepared to dynamically pick up a loose ball and sprint down-court for an easy lay-up. Lastly, extensive research has shown that static stretching before a practice or competition will actually make you slower and weaker; I’m not joking!

Tell Me About This Mobility Stuff...

So what is mobility training? It’s a class of drills designed to take your joints through full ranges of motion in a controlled, yet dynamic context. It’s different from ballistic stretching (mini-bounces at the end of a range of motion), which is a riskier approach that is associated with muscle damage and shortening. In addition to improving efficiency of movement, mobility (dynamic flexibility) drills are a great way to warm-up for high-intensity exercise like basketball. Light jogging and then static stretching are things of the past!

My colleague Mike Robertson and I created a DVD known as Magnificent Mobility to address this pressing need among a wide variety of athletes – basketball players included. We’ve already received hundreds of emails from athletes and ordinary weekend warriors claiming improved performance, enhanced feeling of well-being, and resolution of chronic injuries after performing the drills outlined in the DVD. I think it’s safe to say that they like what we’re recommending! In case that feedback isn’t enough, here are seven reasons why basketball players need mobility.

Reason #1: Mobility training makes your resistance training sessions more productive by allowing you to train through a full range of motion.

We all know that lifting weights improves athletes’ performance and reduces their risk of injury. However, very few people realize the importance of being able to lift through a full range of motion. Training through a full range of motion will carry over to all partial ranges of motion, but training in a partial range of motion won’t carry over to full ranges of motion.

For example, let’s assume Athlete A does ¼ squats. He’ll only get stronger in the top ¼ of the movement, and his performance will really only be improved in that range of motion when he’s on the court.

Now, Athlete B steps up to the barbell and does squats through a full range of motion; his butt is all the way down by his ankles. Athlete B is going to get stronger through the entire range of motion – including the top portion, like Athlete A, but with a whole lot more. It goes without saying that Athlete B will be stronger than Athlete A when the time comes to “play low.”

Also worthy of note is that lifting weights through a full range of motion will stimulate more muscle fibers than partial repetitions, thus increasing your potential for muscle mass gains. If you’re a post-player who is looking to beef up, you’d be crazy to not do full reps – and mobility training will help you improve the range of motion on each rep.

Reason #2: Mobility training corrects posture and teaches your body to get range of motion in the right places.

If you watch some of the best shooters of all time, you’ll notice that they always seem to be in the perfect position to catch the ball as they come off a screen to get off a jump shot. Great modern examples of this optimal body alignment are Ray Allen and Reggie Miller; their shoulders are back, chest is out, eyes are up, and hands are ready. The catch and shot is one smooth, seemingly effortless movement.

By contrast, if you look at players with rounded shoulders, they lack the mobility to get to this ideal position as they pop off the screen. After they receive the ball, they need to reposition themselves with thoracic extension (“straightening up”) just so that they can get into their shooting position. This momentary lapse is huge at levels where the game is played at a rapid pace; it literally is the difference between getting a shot off and having to pass on the shot or, worse yet, having it swatted away by a defender. These athletes need more mobility in the upper body.

As another example, one problem we often see in our athletes is excessive range-of-motion at the lumbar spine to compensate for a lack of range of motion at the hips. Ideally, we want a stable spine and mobile hips to keep our lower backs healthy and let the more powerful hip-joint muscles do the work. If we can’t get that range of motion at our hips, our backs suffer the consequences. Believe it or not, I’ve actually heard estimates that as much as 60% of the players in the NBA have degenerative disc disease. While there are likely many reasons (unforgiving court surface, awkward lumbar hyperextension patterns when rebounding, etc.) for this exorbitant number, a lack of hip mobility is certainly one of them. Get mobility at your hips, and you’ll protect that lower back!

Reason #3: Mobility training reduces our risk of injury.

It’s not uncommon at all to see athletes get injured when they’re out of position and can’t manage to right themselves. If we get range of motion in the right spots, we’re less likely to be out of position, so we won’t have to hastily compensate with a movement that could lead to an ankle sprain or ACL tear.

As an interesting add-on, one study found that a softball team performing a dynamic flexibility routine before practices and competition had significantly fewer injuries than a team that did static stretching before its games (1).

Reason #4: Mobility training will increase range of motion without reducing your speed, agility, strength in the short-term.

Believe it or not, research has demonstrated that if you static stretch right before you exercise, it’ll actually make you weaker and slower. I know it flies in the face of conventional warm-up wisdom, but it’s the truth!

Fortunately, dynamic flexibility/mobility training has come to the rescue. Research has shown that compared with a static stretching program, these drills can improve your sprinting speed (2), agility (3), vertical jump (3-6), and dynamic range of motion (1) while reducing your risk of injury. Pretty cool stuff, huh?

Reason #5: Mobility training teaches you to “play low.”

All athletes want to know how to become more stable, but few understand how to do so. One needs to understand that our stability is always changing, as it’s subject to several environmental and physical factors. These factors include:

1. Body Mass – A heavier athlete will always be more stable. Sumo wrestling…need I say more?

2. Friction with the contact surface – The more friction we can generate (as with appropriate footwear) with the contact surface, the better our stability. Compare a basketball court (plenty of friction) to the ice in a hockey rink (very little friction), and you’ll see what I mean. This also explains why athletes wear cleats and track spikes.

3. Size of the base of support (BOS): In athletics, the BOS is generally the positioning of the feet. The wider the stance, the more stability we are. Again, think sumo wrestling.

4. The horizontal positioning of the center of gravity (COG) – For maximum stability, the COG should be on the edge of the BOS at which an external force is acting. In other words, if an opponent is about to push you at your right side, you’ll want to lean to the right in anticipation in order to maintain your stability after contact.

5. Vertical positioning of the COG: The lower the COG, the more stable the object. You’ll often hear sportscasters talk about Allen Iverson being unstoppable because of his “low center of gravity” or because he “plays low.”

From a training standpoint, we can’t do much for #1, #2, or #4. However, mobility training alone can dramatically impact how well an athlete handles #3 and #5. The better our mobility, the easier it is for us to get wider and get lower. The wider and lower we can get when we need to do so, the better we can maintain our center of gravity within our base of support. Neuromuscular factors – collecting providing for our balancing proficiency – such as muscular strength and kinesthetic awareness play into this as well, and the ultimate result is our stability (or lack thereof) in a given situation.

Reason #6: Mobility training can actually make you taller…Really!

I’ve worked with a lot of basketball players, and I can honestly say that not a single one of them has ever told me that he wants to be shorter. And, I can assure you that the coaches and scouts would take a guy who is 7-0 over a 6-11 prospect any day.

So what does that have to do with our mobility discussion? Well, imagine an athlete who is very tight in his flexors; his hips will actually be slightly flexed in the standing position, as the pelvis will be anteriorly tilted (top of the hip bone is tipping forward). Likewise, if an athlete has tightness in his lats (among other smaller muscles), he’ll be unable to fully reach overhead. These two limitations can literally make an athlete two inches shorter in a static overhead reach assessment.

Just as importantly, such an athlete is going to “play smaller,” too. He won’t jump as high because he can’t get full hip extension and won’t be able to optimally make use of the powerful gluteal muscles. And, his reach will be limited by his inability to get the arms up fully. Together, these factors could knock two inches off his vertical jump and prevent him from making a game-saving block. It really is a game of inches.

Need further proof? I’ve seen several athletes instantly add as much as two inches on their vertical jump just from stretching out the hip flexors and lats before they test. This is an acute change in muscle length, though; mobility training will enable you to attain these ranges of motion all the time.

Reason #7: Mobility and “activation” training teach certain “dormant” muscles to turn on.

In our daily lives and on the basketball court, it’s inevitable that we get stuck in certain repetitive movement patterns – things we do every day, several times a day. With these constant patterns, certain muscles will just “shut down” because they aren’t being used. Two good examples would be the glutes (your butt muscles) and the scapular retractors (the muscles that pull your shoulder blades together). As a result, these shutdowns lead to faulty hip positioning and rounded shoulders, respectively (and a host of other problems, but we won’t get into that).

To correct these problems, we need what is known as activation work. These drills teach dormant muscles to fire at the right times to complement the mobility drills and get you moving efficiently. Mike and I went to great lengths in Magnificent Mobility to not only outline mobility drills, but also activation movements and movements that incorporate components of both.

Reason #8: Having mobility feels good!

Think about it: what’s the first thing an athlete wants to do after a good stretching session? Go run and jump around! Now, just imagine having that more limber feeling all the time; that’s exactly what mobility training can do for you.

Closing Thoughts

Knowledge of the game and technical prowess will take an athlete far in the game of basketball, but it takes an efficient body to build the physical qualities that will take that same athlete to greatness. Without adequate mobility, an athlete will never even reach the efficient stage – much less the next level.

For more information on mobility training, check out MagnificentMobility.com

References

1. Mann, DP, Jones, MT. Guidelines to the implementation of a dynamic stretching program. Strength Cond J. 1999;21(6):53-55.

2. Nelson AG, Kokkonen J, Arnall DA. Acute muscle stretching inhibits muscle strength endurance performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 May;19(2):338-43

3. Kurz, T. Science of Sports Training. Stadion, 2001.

4. Young WB, Behm DG. Effects of running, static stretching and practice jumps on explosive force production and jumping performance. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003 Mar;43(1):21-7.

5. Thompson, A, Kackley, T, Palumbo, M, Faigenbaum, A. Acute effects of different warm-up protocols on jumping performance in female athletes. 2004 New England ACSM Fall Conference. 10 Nov 2004.

6. Colleran, EG, McCarthy, RD, Milliken, LA. The effects of a dynamic warm-up vs. traditional warm-up on vertical jump and modified t-test performance. 2003 New England ACSM Fall Conference. 11 Nov 2003.

|

| Read more |

|

|

Product Review: Alwyn Cosgrove's Afterburn

If you aren't familiar with Alwyn Cosgrove's stuff, you're really missing out; here is a guy who has produced results time and time again. If you're looking to get lean fast, but don't have a clue where to start, let Alwyn show you the way. One of the best aspects of this product is that there's something for everyone. Whether you're a beginner or a seasoned veteran, you'll learn some tricks of the trade to get you to where you want to be faster. I've used a lot of Alwyn's ideas personally and with my athletes and clients; I would encourage you to check them out and experience the results for yourself.

Afterburn

Afterburn

Eric Cressey Interview

Yes, I'm really putting an interview with me in my own newsletter. It's not what you think, though! Brian Grasso from www.DevelopingAthletics.com interviewed me for his newsletter last week; I hope you enjoy it!

Eric Cressey is one of the youngest and brightest stars in the conditioning world today. He and I have forged a great relationship as of late and I wanted to bring his expertise to you... you WILL be impressed!

BG - Your newest DVD, Magnificent Mobility cites the importance of delineating the difference between "mobility" and "flexibility" in a training program. What is the difference and when do each apply?

EC – Those are great questions, Brian; very few people understand the difference – and it is a big one. Flexibility merely refers to range of motion – and, more specifically, passive range of motion as achieved by static stretching. Don’t get me wrong; static stretching has its place. I see it as tremendously valuable in situations where you want to:

a) Relax a muscle to facilitate antagonist activation (e.g. stretch the hip flexors to improve glute recruitment)

b) Break down scar tissue following an injury and/or surgery (when the new connective tissue may require “realignment”)

c) Loosen someone up when you can’t be supervising them (very simply, there is less likelihood of technique breakdown with static stretching because it isn’t a dynamic challenge)

However, the principle problem with pure flexibility is that it does not imply stability nor preparedness for dynamic tasks. As one of my mentors, Dr. David Tiberio, taught me, we need to have mobile-stability; there’s really no use in being able to attain a given range of motion if you can’t stabilize yourself in that position. Excessive passive flexibility without mobility (or dynamic flexibility, as it’s been called) will actually increase the risk of injury!

Moreover, it’s not uncommon at all to see individuals with circus-like passive flexibility fail miserably on dynamic tasks. For instance, I recently began working with an accomplished ballet dancer who can tie herself into a human pretzel, but could barely hit parallel on a body weight squat until after a few sessions of corrective training. She was great on the dynamic tasks that were fundamentally specific to her sport, but when faced with a general challenge that required mobility in a non-familiar range of motion, she was grossly unprepared to handle it. She had flexibility, but not mobility; the instability and the lack of preparation for the dynamic motion were the limiting factors. She could achieve joint ranges of motion, but her neuromuscular system wasn’t prepared to do much of anything in those ranges of motion.

We went to great lengths in Magnificent Mobility to not only outline mobility drills, but also what we call “activation” movements. Essentially, they teach often-dormant muscles to fire at the right times to normalize the muscle balance, improve performance, and reduce the risk of injury. Collectively, mobility and activation drills are best performed as part of the warm-up and on off-days as active recovery. We’ve received hundreds of emails already from athletes and ordinary weekend warriors claiming improved performance, enhanced feeling of well-being, and resolution of chronic injuries; this kind of positive feedback really makes our jobs fun!

BG – You certainly are known for you ability to get athletes stronger. What type of training do you use for adolescent athletes… let me narrow that down (i) a 16 year old with no formal strength training experience (ii) a 16 year with a solid foundation and decent knowledge with exercise form

EC - First and foremost, we have fun. It doesn’t matter how educated or passionate I am; I’m not doing my job if they aren’t having a blast coming in to train with me. With respect to the individual athletes, I’ll first roll through a health history and just run them through some basic dynamic flexibility movements to see where they stand. As we all know, there is a lot of variation in terms of physical maturity and training experience at these ages, and I can get a pretty good idea of what they need just by watching them move a bit. In your individual cases, much of my training would revolve around the following:

In the unprepared athlete, I’d go right into several body weight drills – many of them isometric in nature – to teach efficiency. We often see an inability to differentiate between lumbar spine and pelvic motion, so I spend quite a bit of time emphasizing that the lumbar spine should be stable, and range of motion should come from the hips, thoracic spine, scapulae, and arms. Loading is the least of my concerns in the first few sessions; research has demonstrated that beginners can make progress on as little as 40% of 1RM, so why rush things with heavy loading that will compromise form? The lighter weights will allow them to groove technique and improve connective tissue health prior to the introduction of heavier loading.

At the start, I’ll emphasize unilateral work; mobility; any corrective training that’s needed; classic stabilization movements (i.e. bridges); and learning the compound movements, deceleration/landing mechanics, and how to accelerate external loads (e.g. medicine balls, free weights). I’ll also make a point of mentioning that how you unrack and rerack weights is just as important as how you train; it drives me crazy to see a kid return a bar to the floor with a rounded back.

In the athlete with a solid foundation, I’ll run through those same preliminary drills to verify that they are indeed “solid” and not just good compensators for dysfunction. Believe it or not, most “trained” athletes really aren’t that “trained” if you use efficiency as a marker of preparedness – even at the Division I, professional, and Olympic ranks; you can be a great athlete in spite of what you do and not necessarily because of what or how you do it.

Assuming things are looking good, I’ll look to give them more external loading on all movements, as the fastest inroads to enhanced performance will always be through maximal strength in novice athletes. As they get more advanced, I’ll start to look more closely at whether they’re more static or spring dominant and incorporate more advanced reactive training movements. Single-leg movements are still of paramount importance, and we add in some controlled strongman-type training to keep things interesting and apply the efficiency in a less controlled environment. Likewise, as an athlete’s deceleration mechanics improve, we progress from strictly closed-loop movement training drills to a blend of open- and closed-loop (unpredictable) tasks.

In both cases, variety is key; I feel that my job is to expose them to the richest proprioceptive environment possible in a safe context. With that said, however, I’m careful to avoid introducing too many different things; it’s important for young athletes to see quantifiable progress in some capacity. If you’re always changing what you do, you’ll never really show them where they stand relative to baseline.

BG – Olympic lifts and adolescents… do you use them? Why or why not?

EC – Personally, I generally don’t for several reasons. It’s not because I’m inherently opposed to Olympic lifts from an injury risk standpoint. Sure, I’ve seen cleans ruin some wrists, and there are going to be a ton of people with AC joint and impingement problems who can’t do anything above shoulder level without pain. That’s not to say that the exercises are fundamentally contraindicated for everyone, though; as with most things in life, the answer rests somewhere in the middle. Know your clients, and select your exercises accordingly.

My primary reasons for omitting them tend to be that I don’t always have as much time with athletes as I’d like, and simply because such technical lifts require constant practice – which we all know isn’t always possible with young athletes who don’t train for a living. Equipment limitations may be a factor (bumper plates are a nice luxury). And, to be very honest, I’ve seen athletes make phenomenal progress without using Olympic lifts, so I don’t concern myself too much with the arguing that goes on. If another coach wants to use them and is a good teacher, I’m find with him doing so; it just isn’t for me, with the exception of some high pulls here and there.

BG – Basing off of the last question, do you teach Olympic lift technique to pre-adolescents?

EC – I don’t. It’s not to say that I wouldn’t be comfortable doing so with a broomstick or some PVC pipe, but when I consider the pre-adolescents with whom I’ve worked, I just can’t see them getting excited about all that technique work for one category of exercises. Olympic lifting is a sport in itself, and I think it should be viewed that way.

BG – My subscribers know that I believe as much in deceleration training as I do in any sort of speed enhancing-based work… How do you improve speed and deceleration habits?

EC – We’re definitely on the same page on this one. In a nutshell, I just slow everything down for the short-term – starting with isometric holds. Every change of direction has a deceleration, isometric action, and acceleration; I’ve found that if you teach the athlete how his/her body should be aligned in that mid-point, they’ll be golden. My progressions are as follows (keep in mind that you can span several of these progressions in one session if the athlete is proficient):

Slow-speed, Full Stop, Hold > Slow Speed, Full Stop, Acceleration > Slow Speed, Quick Transition,

Acceleration > Normal Speed, Full Stop, Hold > Normal Speed, Full Stop, Acceleration > Normal Speed, Quick Transition, Acceleration

Open-loop > Closed-loop (predictable > unpredictable)

With respect to reactive training methods (incorrectly termed plyometrics), we start with bilateral and unilateral jumps to boxes, as they don’t impose as much eccentric force (the athlete goes up, but doesn’t come down). From there, we move to altitude landings, and ultimately to bounce drop jump (depth jumps), repeated broad jumps, bounding, and other higher-impact tasks.

Finally, one lost component of deceleration training is basic maximal strength. All other factors held constant, the stronger kid will learn to decelerate more easily than his weaker counterparts. So, enhancing a generally, foundational quality like maximal strength on a variety of tasks will indirectly lead to substantial improvements in deceleration ability – especially in untrained individuals.

Another week in the books! Thanks for checking in.

Until next time, train hard and have fun!

EC

|

| Read more |

|

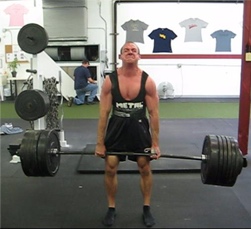

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|