|

| Nick Grantham:

I like to develop what we call 'bulletproof' athletes - men and women that can take to the field and cope with what the sport and their opponents throws at them. What would be your main tips for making a 'bullet proof' athlete - what areas should we focus our attention on and what exercises could we use?

Eric Cressey:

1. Adequate hip mobility.

2. Stability of the lumbar spine, scapulae, and glenohumeral joint.

3. Posterior chain strength and normal firing patterns

4. Loads of posterior chain strength.

5. More pulling (deadlifts, rows, and pull-ups) than pushing (squats, benches, and overhead pressing)

6. Greater attention to single-leg movements

7. Prioritization of soft-tissue work in the form of foam rolling, ART, and massage

8. Attitude (being afraid when you’re under a bar is a recipe for injury)

9. Adequate deloading periods

10. Attention to daily posture (you have 1-2 hours per day to train, and 22-23 to screw it up in your daily life)

Eric Cressey |

| Read more |

|

Honestly, the word “core” has become so hackneyed that it makes me kind of ashamed that our profession. I mean, let’s face it: “Core” can essentially be translated as “The rectus abdominus, lumbar erectors, obliques, and all those other muscles between the knees and shoulders that I’m either too lazy or misinformed to list.”

Everything is related; our bodies are great at compensating. As such, it’s imperative that the approach one takes to “core” training be based on addressing where the problems exist. The most common lower back problems we see are related to extension-rotation syndrome. We most often get hyperextension at the lumbar spine because our gluteus maximus doesn’t fire to complete hip extension and posteriorly tilt the pelvis; we have to find range of motion wherever we can get it. Having tight hip flexors and lumbar erectors exaggerates anterior pelvic tilt, so this hyperextension is maintained throughout the day to keep the body upright in spite of the faulty pelvic alignment.

The rotation component simply comes along when you throw unilateral dominance into the equation. It might be a baseball pitcher always throwing in one direction, or an office worker always turning to answer the phone on one side. Lumbar rotation is not a movement for which you want any extra range of motion, and the related hip hiking isn’t much fun to deal with, either.

The solution is to get the glutes firing and learn to stabilize the lumbar spine while enhancing mobility at the hips, thoracic spine, and scapulae. You just have to get the range of motion at the right places.

Unfortunately, thinking this stuff out isn’t high on some people’s priority list. It’s “sexier” to tell a client to do some weighted sit-ups, Russian twists, and enough yoga to make the hip flexors want to explode. I’m not going to recommend sit-ups to anyone, and if an athlete is going to do something advanced, he’s going to have shown me that he’s prepared for it by successfully completing a progression to that point. You can get away with faulty movement patterns in the real world, but when you put a faulty movement pattern under load in a resistance training context, everything is magnified.

Eric Cressey

Start with the right plan. |

| Read more |

|

In December of 2001, I was rear-ended going about 30mph; five cars were involved, and I was the first car hit from behind. My knee hit the dashboard when I was hit from behind and my head was jerked backwards when I hit the car in front of me.

My knee started hurting soon after, although I never got it checked out. It’s now become a sharp pain and a constant, dull ache as well with weakness on stairs and squatting-type positions especially. In addition, there are tender areas, on the outside and top of the knee, that cause extreme pain when I am bending, squatting, lying down, or sitting down for too long. My hip has also been affected, also aching constantly. My right leg and knee also hurt and knot up easily. The surrounding muscles are very weak with several knots in them, and I also have a very tight iliotibial band. Any ideas what might be going on?

I thought "PCL" (posterior cruciate ligament) the second I saw the word "dashboard;" it's the most common injury mechanism with this injury. I’m really surprised that they didn’t check you out for this right after the accident; you might actually be a candidate for a surgery to clean things up. Things to consider:

1. They aren't as good at PCL surgeries as they are with ACL surgeries, as they're only 1/10 as common. As such, they screw up a good 30%, as I recall – so make sure you find a good doctor who is experienced with this injury to assess you and, if necessary, do the procedure.

2. It's believed that isolated PCL injuries never occur; they always take the LCL and a large "chunk" of the posterolateral complex along for the ride. That would explain some of the lateral pain.

3. The PCL works synergistically with the quads to prevent posterior tibial translation. As such, quad strengthening is always a crucial part of PCL rehab (or in instances when they opt to not do surgery). A good buddy of mine was a great hockey player back in the day, but he has no PCL in his right knee; he has to make up for it now with really strong quads.

4. Chances are that a lot of the pain you’re experiencing now is related more to the compensation patterns you’ve developed over the years than it is to the actual knee injury. For instance, the tightness in your IT band could be related to you doing more work at the hip to avoid loading that knee too much. Pain in the front of the knee would be more indicative of a patellar tendonosis condition (“Jumper’s Knee”), which would result from over-reliance on your quads because of the lack of the PCL (something has to work overtime to prevent the portion of posterior tibial translation that the PCL normally resisted).

5. From an acute rehabilitation standpoint, I think you’d need to address both soft tissue length (with stretching and mobility work) and quality (with foam rolling). These interventions would mostly treat the symptoms, so meanwhile, you’re going to need to look at the deficient muscles that aren't doing their job (i.e. the real reasons that ITB/TFL complex is so overactive). I'll wager my car, entire 2006 salary, and first-born child that it’s one or more of the following:

a) your glute medius and maximus are weak

b) your adductor magnus is overactive

c) your ITB/TFL is overactive (we already know this one)

d) your biceps femoris (lateral hamstring) is overactive

e) your rectus femoris is tighter than a camel's butt in a sandstorm

f) you might have issues with weakness of the posterior fibers of the external oblique, but not the rectus abdominus (most exercisers I know do too many crunches anyway!)

Again, your best bet is to get that PCL checked out and go from there. If you’ve made it from December 2001 until now without being incapacitated, chances are that you’ll have a lot of wiggle room with testing that knee out so that you can go into the surgery (if there is one) strong.

Eric Cressey |

| Read more |

|

Eric Cressey

They say that experience is the only thing that can truly yield perspective; I’d say that you’re a perfect example of that. Speaking of experience, what were some of the mistakes you’ve made along the way, and what would you do differently?

Bob Young

I’m not even sure where to start on this one. The easiest way to explain this would be to quote Alwyn Cosgrove, “A complete training program has to include movement preparation, flexibility work, injury prevention work, core work, cardiovascular work, strength training, and recovery/regeneration. Most programs cover, at best, two of those.”

My program only included strength training and some core work for the longest time, and I am now paying for that with chronic injuries. Now, I have had to learn about the other parts that I was missing; the more I incorporate this stuff, the better I feel. However, 15 years of not doing what I should have been doing has really cost me. I have torn my pec major, triceps tendon, intercostal, and biceps tendon. I also currently have a bulging disk in my lower back.

Could all these have been avoided? Probably not all of them, but I think some of them could have. If I had to name the biggest mistakes, it would be not using a foam roller and not doing any mobility work. In the two months I have been using the foam roller my tissue quality has improved dramatically. I have been doing mobility work, under your guidance, for about a month and I have seen some incredible improvements.

Eric Cressey

Correct your Training and Improve your Performance. |

| Read more |

|

Eric Cressey:

If you had to pick five things our readers could do right now to become better lifters/athletes/coaches/trainers, what would they be?

Mike Robertson:

1. Start getting some soft tissue work done!

As Mike Boyle says, “If you aren’t doing something to improve tissue quality, you might as well stop stretching, too.” I firmly agree with him on this point, and while it may cost a few bucks, it’s going to help keep you healthy and hitting PR’s. This could be as simple as foam rolling, or as extreme as getting some intense deep tissue massage or myofascial release done. I’ve tried it all and all of it has its place.

2. Don’t neglect mobility work!

Ever since we released our Magnificent Mobility DVD, people are finally starting to see all the benefits of a proper warm-up that includes dynamic flexibility/mobility work. However, just because you understand the benefits doesn’t mean squat if you aren’t doing it! Take the time to get it done before every training session, and even more frequently if need be.

3. Understand functional anatomy

Again, you and I (along with many others), have preached this for quite some time, but I’m not sure enough people really understand how the human body works. Hell, I think I do, and then I get into some of these intense anatomy and PT related books and find out tons of new info!

Along these same lines, if you don’t understand functional anatomy, you really have no business writing training programs, whether they’re for yourself or for others. That may sound harsh, but for whatever reason people read a couple copies of Muscle and Fiction and think they can write programs. I’ve fixed enough broken people to know that very few people can integrate the functional anatomy into what amounts to functional programming (and no, that doesn’t include wobble boards, Airex pads, etc.).

Train your athletes at the next level.

4. Train to get stronger

While I’m all for all the other stuff that goes into training (proper recovery, mobility work, soft tissue work, conditioning, etc.), I think too many people want all the bells and whistles but forget about the basics. GET YOUR ATHLETES STRONG! Here’s the analogy that I use: performance coaches are asked to balance their training so that the athlete: a) improves performance and b) stays healthy. What I see right now is a ton of coaches that focus on all this posture and prehab stuff, but their athletes aren’t really that much better anyway. You have to work on both end of the spectrum.

Think about it like this: Let’s say you have this huge meathead that’s super strong but has no flexibility, mobility or conditioning, then throw him on the field. He may last for a while, but eventually he’s going to get hurt, right? You haven’t covered the spectrum.

But what’s the opposite situation? We have the coach who focuses on posture, prehab, etc., and the athlete has “optimal” muscle function but is weak as a kitten. Are you telling me this kid isn’t at a disadvantage when he steps on the field or on the court? Again, you haven’t covered the spectrum.

In other words, feel free to do all the right things, but don’t forget about simply getting stronger; as you’ve said, it’s our single most precious training commodity.

5. Keep learning!

I’m not going to harp too much on this one; simply put, you need to always be expanding your horizons and looking to new places for answers. There’s a plethora of training knowledge out there, and what you don’t know can come back to haunt you. I believe it was Ghandi who said, “Live like today was your last, but learn like you will live forever.” That’s pretty solid advice in my book (and hopefully the last quote I’ll throw in!)

Eric Cressey

For more information on Mike Robertson check out his blog and his website. |

| Read more |

|

You certainly are known for your ability to get athletes stronger. What type of training do you use for adolescent athletes… let me narrow that down (i) a 16 year old with no formal strength training experience (ii) a 16 year with a solid foundation and decent knowledge with exercise form

First and foremost, we have fun. It doesn’t matter how educated or passionate I am; I’m not doing my job if they aren’t having a blast coming in to train with me. With respect to the individual athletes, I’ll first roll through a health history and just run them through some basic dynamic flexibility movements to see where they stand. As we all know, there is a lot of variation in terms of physical maturity and training experience at these ages, and I can get a pretty good idea of what they need just by watching them move a bit. In your individual cases, much of my training would revolve around the following:

In the unprepared athlete, I’d go right into several body weight drills – many of them isometric in nature – to teach efficiency. We often see an inability to differentiate between lumbar spine and pelvic motion, so I spend quite a bit of time emphasizing that the lumbar spine should be stable, and range of motion should come from the hips, thoracic spine, scapulae, and arms. Loading is the least of my concerns in the first few sessions; research has demonstrated that beginners can make progress on as little as 40% of 1RM, so why rush things with heavy loading that will compromise form? The lighter weights will allow them to groove technique and improve connective tissue health prior to the introduction of heavier loading. At the start, I’ll emphasize unilateral work; mobility; any corrective training that’s needed; classic stabilization movements (i.e. bridges); and learning the compound movements, deceleration/landing mechanics, and how to accelerate external loads (e.g. medicine balls, free weights). I’ll also make a point of mentioning that how you unrack and rerack weights is just as important as how you train; it drives me crazy to see a kid return a bar to the floor with a rounded back.

In the athlete with a solid foundation, I’ll run through those same preliminary drills to verify that they are indeed “solid” and not just good compensators for dysfunction. Believe it or not, most “trained” athletes really aren’t that “trained” if you use efficiency as a marker of preparedness – even at the Division I, professional, and Olympic ranks; you can be a great athlete in spite of what you do and not necessarily because of what or how you do it.

Assuming things are looking good, I’ll look to give them more external loading on all movements, as the fastest inroads to enhanced performance will always be through maximal strength in novice athletes. As they get more advanced, I’ll start to look more closely at whether they’re more static or spring dominant and incorporate more advanced reactive training movements. Single-leg movements are still of paramount importance, and we add in some controlled strongman-type training to keep things interesting and apply the efficiency in a less controlled environment. Likewise, as an athlete’s deceleration mechanics improve, we progress from strictly closed-loop movement training drills to a blend of open- and closed-loop (unpredictable) tasks.

In both cases, variety is key; I feel that my job is to expose them to the richest proprioceptive environment possible in a safe context. With that said, however, I’m careful to avoid introducing too many different things; it’s important for young athletes to see quantifiable progress in some capacity. If you’re always changing what you do, you’ll never really show them where they stand relative to baseline.

Eric Cressey

A Great Athlete is an Efficient Athlete. |

| Read more |

|

Strength coaches have in recent years emerged as critical components to top level athletes looking for the competitive edge. What advice would you impart on those seeking a career in this field?

1. Learn functional anatomy.

2. Read at least one hour per day.

3. Surround yourself with people who are doing what you want to do professionally and personally – good lifters and coaches. Intern, drive hours to train, etc. Build a big network.

4. Read “How to Win Friends and Influence People” by Dale Carnegie. It has nothing to do with training, but everything to do with being successful in whatever it is you do. The same goes for “Under the Bar” by Dave Tate.

5. Recognize that you’re more than just a strength coach and be versatile: mobility, regeneration strategies, nutrition, speed training, etc. It’s not just about strength.

6. Work smarter instead of longer. If you train people 12 hours per day, cut back and consolidate your clients into group training sessions. Use the time you’ve freed up to read, call/visit other coaches, and do what it takes to make yourself better. Income is temporary; knowledge sticks around forever.

7. When you’re starting out, read three training books to every one business book. Once you’ve been rolling for a while, shift it to a 1:1 ratio. Learn to leverage the abilities and knowledge you’ve accumulated.

8. Compete in something. Chess. Curling. Anything. Just do whatever it takes to share the competitive mindset with your athletes.

9. Swear less and coach/cue more. Athletes get desensitized to your yelling, and you look like a tool. Almost all of the best coaches I’ve ever seen have been relatively quiet in the weight room; it’s because they coach well at the beginning, so they just needed to sit back and fine-tune tactfully as time goes on.

10. Your #1 responsibility in working with an athlete/client is to not f**k them up. Your #2 responsibility is to provide programming and coaching that will prevent injury. Training to enhance performance is #3, but in every case, attending to #1 and #2 will always get you started on #3.

Eric Cressey

|

| Read more |

|

Any lifts you would say are indispensable, no matter what type of sport one is involved in?

Well, we know people need to squat, deadlift, bench, row, and do chin-ups, but for whatever reason, the big ones I see people overlooking are single-leg movements – and I’m not just talking about lunges. You need to look at three different categories:

1. Static Unsupported – 1-leg squats (Pistols), 1-leg RDLs

2. Static Supported – Bulgarian Split Squats

3. Dynamic – Lunges, Step-ups

From there, you can also divide single-leg movements into decelerative (forward lunging) and accelerative (slideboard work, reverse lunges). I’ve found that accelerative movements are most effective early progressions after lower extremity injuries (less stress on the knee joint). I think that it’s ideal for everyone to aim to get at least one of each of the three options in each week. If one needed to be sacrificed, it would be static supported. Because static unsupported aren’t generally loaded as heavily and don’t cause as much delayed onset muscle soreness, they can often be thrown in on upper body days.

Of course, I’m the corrective exercise guy, so people obviously need to be doing their mobility and activation drills along with plenty of scapular stability and rotator cuff work.

Eric Cressey |

| Read more |

|

I was trying to put together a couple warm ups from The Ultimate Off-Season Training Manual as well as the Magnificent Mobility and Inside-Out DVD. It looks like The Ultimate Off-Season Training Manual has a lot of exercises from Magnificent Mobility, although it also has foam rolling.

I'm thinking of adding a little foam rolling before the mobility/activition drills, but also was wondering about the upper body days. I know there is a lot of difference in the Inside-Out recommnedations and what is in The Ultimate Off-Season Training Manual. Should I lean more towards what is the Inside-Out DVD, or try to make a combination of what is in The Ultimate Off-Season Training Manual and the Inside-Out DVD?

Go with a combination. Here's a taster of what I'm using with one of my athletes this month, as an example.

Lower Body Days

Foam Rolling:

-IT Band/Tensor Fasciae Latae

-Quads

-Hip Flexors

-Adductors

-Thoracic Extension

-Piriformis (tennis ball)

-Calves (tennis ball)

-Lats

-Infraspinatus (tennis ball)

Seated 90/90 Static Stretch 15s/side

Warrior Lunge Static Stretch 15s/side

Birddog 8/side

Wall Ankle Mobilizations 8/side

Hip Corrections 8/side

Pull-Back Butt Kick 5/side

Cradle Walk 5/side

Walking Spidermans 5/side

Bowler Squats 8/side

Overhead Lunge Walks 5/side

Quadruped Extension-Rotation 8/side

Split-Stance Broomstick Pec Mobilizations 8/side

Upper Body Days

Foam Rolling:

-IT Band/Tensor Fasciae Latae

-Quads

-Hip Flexors

-Adductors

-Thoracic Extension

-Piriformis (tennis ball)

-Calves (tennis ball)

-Pecs

-Infraspinatus (tennis ball)

Seated 90/90 Static Stretch 15s/side

Warrior Lunge Static Stretch 15s/side

Supine Bridge 1x12

X-band Walk 12/side

Windmills 10/side

Multiplanar Hamstrings Mobilizations 5/5/side

Reverse Lunge with Posterolateral Reach 5/side

Squat-to-Stand w/Diagonal Reach 5/side

Levator Scapulae/Upper Trap Stretch 15s/side

Side-Lying Internal-External Rotations 8/side

Scap Pushup 1x15

Scapular Wall Slides 1x12

All Warm-Ups Barefooted

Eric Cressey

Why Magnificent Mobility:

The principle problem with pure flexibility is that it does not imply stability nor readiness for dynamic tasks. We need to have mobile-stability at all our joints; there’s really no use in being able to attain a given range of motion if you can’t stabilize yourself in that position. Excessive passive flexibility without mobility (or dynamic flexibility, as it’s been called) will actually increase the risk of injury! Amazingly, it’s not uncommon at all to see individuals with circus-like passive flexibility fail miserably on dynamic tasks. Don't fall behind. |

| Read more |

|

Q: Cricket is essentially a “speed-strength” based game - hitting, throwing and running. However, it requires players to play for long periods - anything between 2-6 hours a day. How can players include these opposing factors in their training?

A: One of the things you always have to concede with any sport is that you're always going to be riding a few horses with one saddle. Ironman competitors will never squat 500 with their aerobic training stimuli, and powerlifters won't compete in Ironman events because training to do so would interfere with their strength gains. All other sports fall somewhere in the middle between these extremes.??From a general standpoint, you train to become more efficient as an athlete. First, you have to do so biomechanically by ironing out muscle imbalances. You need to be a better athlete before you can be a better cricket player. So, mobility and activation work, soft-tissue quality initiatives, and appropriate resistance training is key to success on this front.??Next, you have to be efficient in the context of your sporting movements - and that's where tactical work comes in.??What you're referring to with this question is one-third of the efficiency equation: metabolic efficiency. The more aerobic a sport, the sooner you'll need to prioritize intensive metabolic conditioning in the off-season period. So, a soccer player would require it sooner than a football player. I go into great detail on this in The Ultimate Off-Season Training Manual.??Cricket is a bit of middle-ground, though. From a duration standpoint, it's clearly a long event at times. However, it isn't necessarily continuous; it's more along the lines of what you see in baseball - which is basically a completely anaerobic sport. You sprint, stand around for an extended period, and sprint again - possibly even 30-60 minutes later! Just because the matches/games last 4-5 hours doesn't mean that they're aerobic - or that you need to train for them with repeated bouts of high-intensity exercise with INCOMPLETE rest.??My suggestion is to do what it takes to be fast and powerful - and let the duration of the matches just fall into place. Attend to nutrition/hydration and recovery protocols well, and the physical qualities you've built will sustain themselves in spite of the duration of the match. And, if you're crazy athletic, chances are that you'll win those matches a lot sooner.

Eric Cressey

Get your Questions Answered.

Don't Make The Same Mistakes as your Competition. Utilize Your Off-Season. |

| Read more |

|

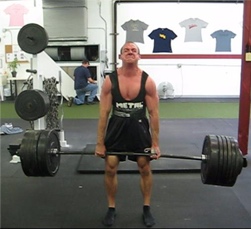

LEARN

HOW TO

DEADLIFT

- Avoid the most common deadlifting mistakes

- 9 - minute instructional video

- 3 part follow up series

|